Ethnic tensions and xenophobia follow Burmese refugees across borders.

Despite independence in 1948, Burma has been plagued by problems since the military junta took state control in 1962. Power struggles, conflict, occupation, resource extraction and ethnic tensions have all incited Burma’s displacement issue. While exact numbers are unknown, estimates are in the region of 1 million internally displaced and 1 million fleeing to neighboring countries.

Recently, the media has recognized the crisis that is happening in Rakhine State, Burma, where Buddhist and Muslim tensions have forced many Rohingya to flee, even though their safety options elsewhere are limited. However, Burma is made up of 136 different ethnic groups and many that are unrecognized — the dominating group being the Barma (the indigenous majority). Many tribes belong to one overarching regional group; but even within that group, tribal rivalries exist.

Making it in Malaysia

Returning from a recent trip to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, I volunteered at a school set up for Burmese refugee children. The school consisted of children between the ages of five and 12, all from the Matu tribe of the Chin group. The Chin are the largest Burmese ethnic group in Malaysia and have fled Burma due to military occupation and persecution by the Barma.

The school was housed in an unkempt apartment in the backstreets of Bukit Bintang (downtown Kuala Lumpur’s main shopping street), and was given some assistance by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Although true, they relied heavily on volunteers and private generosity for funding. Seventeen-year-old Sara coordinated the school, and she, like many others, was waiting for resettlement and seeking English language skills needed to prepare her for the US.

There are nearly 94,000 refugees and asylum seekers from Burma residing in Malaysia. They often live in squalid conditions in overcrowded apartments within the capital, or in makeshift camps on the outskirts of the Klang Valley and the Cameron Highlands. In order to survive, they work in the informal sector on low wages in occupations that make up the three Ds: dirty, dangerous, and difficult. Many employers exploit their vulnerable situation and do not pay them at all. Children do not have access to formal education, but some do attend community-run learning centers like the one Sara ran. Refugees can access healthcare services, but they are not free and are far too costly for most. They have no access to benefits, as Malaysia is not a signatory to the Refugee Convention and the general registration process closed in 2006.

Due to the squalid conditions in which they live, disease is widespread, and they experience pervasive abuse from the authorities who continually threaten them if they are caught extracting bribes or subjecting them to physical abuse. However, the Malaysian government does cooperate with the United Nations, and the UNHCR office still exists. Displaced persons can still register with the office in order to gain resettlement in a third country, as Sara did.

Communal Responses

Holding a UNHCR card does not provide irregular migrants with protection or access to benefits and services, so these groups have to rely on forming communities for the provision of informal services and for coordinating help from NGOs. The ethnic tensions that divide Burma were not left at home, but instead exported to Malaysia.

The school that Sara coordinated had a maximum of 15 children of mixed ages. Children were split between kindergarten and “the rest.” This made delivering lessons suitable for everyone challenging, as children as young as seven were included in grammar sessions for teenagers. While Sara’s efforts are highly commendable, the education model is far from ideal and could be improved if two or more schools were to collaborate and combine resources. Michael, one of the main volunteers, commented that there was no chance of another school collaborating with this school, as the children are from the Matu tribe and hated by other tribes. Therefore, collaboration could never happen.

However, there are some organizations that are trying to overcome this problem in order to gain common goals. The Alliance of Chin Refugees, for example, is an informal NGO that tries to unite different Chin groups in order to provide a community center, so issues can be resolved constructively. They have helped the wider Chin community by acting as a correspondent for the UNHCR resources and registration of newly arriving NGOs providing healthcare clinics. They organize schooling and help women to market their handicrafts. Another group, the Chin Emergency Relief Group, was also formed to tackle social issues within the community — homelessness, in particular. The Chin Refugee Committee works closely with the UNHCR to assist and facilitate their operations in Kuala Lumpur, providing a safe house for Chin people in need.

The second largest ethnic group from Burma currently present in Malaysia is the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group from Rakhine state. Rendered stateless by the Burma Citizenship Law of 1982, they have been subjected to persecution, discrimination and intrusive restriction on their rights to marry and have families. Like the Chin in Malaysia, they have no access to benefits or services and no protection even if they are registered with the UNHCR. The separation of the Rohingya by the international community and by Burmese groups has led to an overall lack of support, resulting in extreme illiteracy, substandard health and living conditions with little hope for improvement. Due to their lack of status, children do not have access to the school system, nor may they share services with the Chin.

There has been some civil society response, however, and in 2008, the Burmese Rohingya Refugees Community Malaysia (BRRCM) was set up with their headquarters in Penang. They work on key issues affecting the Rohingya — for example, status: the Rohingyas’ situation is further complicated because they are “stateless,” and not recognized by any country. The BRRCM work with the UNHCR to enable registration of refugee status along with their own “registration letter,” claiming they are asylum seekers.

The effect this has in protecting Rohingya from RELA (a civilian para-policing group that tackle illegal immigration) and the police is unclear, but they feel this is better than nothing. If members of the Rohingya are detained, they work with organizations such as Suhakam (the Malaysian Human Rights Commission) and UNHCR to mitigate any violence or abuse they may have encountered. They also collect data to inform their work and provide a platform for interested parties such as students or film-makers, to gain knowledge on the plight of the Rohingya and their experience in Malaysia.

In order to join forces when possible, they have formed part of the organization named the All Burmese Muslims Council Malaysia (ABMCM), which they set up in 2009 to enable them to pursue common goals. With regard to basic services such as health, BRRCM links to local organizations to help organize provision of services such as free medical camps for basic health screenings and to tackle emergency health problems. In 2008, there were nearly 350 seriously sick Rohingyas, who were immobile and unable to seek medical treatment. BRRCM informed a local group, who immediately sent a team of doctors and ancillaries to attend to them in Bagan Dalam, Butterworth. The doctors diagnosed their illnesses and provided them with antibiotics, iron tablets, ointment and multi-vitamins.

What’s Next?

Community and civil society-led provisions are only drops in the ocean toward providing migrants from Burma with the dignity of living a free and fair existence – one where they can fully realize their human rights. Ultimately, the solution to this is for the Burmese government to be called to account or take action on the abuse within Burma.

The international community will have to focus its humanitarian and political lens on this area so there is a safe place to return to. Within Malaysia, non-cohesive services between the two groups or any other Burmese ethnic groups, cause disparities in the level of services available to minority ethnic groups.Thus, both groups seem to encounter similar problems around access to formal services. UNHCR provides no guarantee of protection and this needs to change. The national authorities must recognize their status and refrain from detaining individuals. Therefore, the Malaysian government must ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and establish an official process.

The Rohingya seem to have the added disadvantage of not being recognized as belonging to a state – they belong niether to Burma or Bangladesh. Their particular situation and long-standing persecution should mean that the UNHCR and resettlement countries revise their policies to include the Rohingya more centrally in resettlement programs. This might create incentives for destination countries such as Malaysia to provide more sustainable solutions for populations who cannot return and are forced to remain refugees.

Donors also have a role to play, as they can urge governments to ease restrictions on the Rohingya and support programs that will lead to more self-reliance. Though complex, the issue of tribal rivalry and xenophobia amongst Burmese groups should be tackled, even outside of Burma. Not only would more solidarity enable them to survive and cope better within interim host countries such as Malaysia, these refugees will eventually have to move on to other countries where such attitudes would not be tolerated. Therefore, there is a role for impartial NGOs to mediate between groups and provide education on social and racial cohesion.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

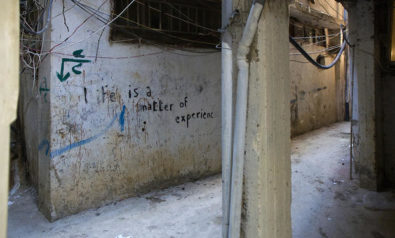

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment