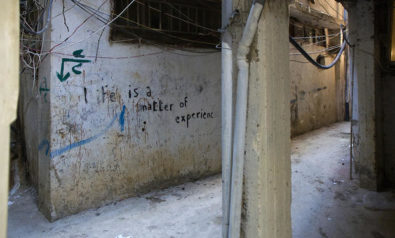

Social and economic gains of Palestinian refugees have changed due to the Syrian conflict.This is the last of a two part series. Read part one here.

Such was the status of Palestinian refugees in Syria at the advent of the popular uprising against Bashar al-Assad’s regime in early 2011. From the beginning, Syria’s Palestinian community was a principal, if involuntary, actor in the unfolding drama of the uprising. In the early stages of the conflict, the Palestinian community at large attempted to maintain neutrality, in line with a longstanding tradition of avoiding entanglement in domestic political disputes.

So potent was their initial desire to remain uninvolved in the conflict that Palestinian protestors torched the headquarters of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command, the regime’s closest allied Palestinian faction, when it sided with the government and undermined the call for neutrality.

However, as time went on, ordinary Palestinians found themselves increasingly involved as the regime attempted to scapegoat their community as a foreign interlocutor. The proximity of Palestinian refugee camps to the sites of initial protest in Dara’a and Latakia led regime officials to accuse Palestinians of instigating the violence in an attempt to downplay “indigenous” Syrian support for, and participation in, the protests.

Moreover, as the regime assault on Syrian dissidents intensified, many Palestinians felt compelled to aid them. This was the case among refugees in the Dara’a refugee camp who elected to host a field hospital in the camp for Syrians requiring medical attention. This level of involvement marks a break with past traditions of Palestinian political activity in Syria.

Before the uprising, such activity was largely restricted to matters directly connected to Palestinian liberation and the right of return. Historically, Palestinians did not engage in Syria’s domestic politics. A report from Al Jazeera’s research arm reveals surprising motivations for this shift among at least some Palestinian refugees: feelings of Syrian political identity and obligation.

According to one activist, the uprising marks “the first time we feel Syrian… this intifada is about the whole of Syria, as this country is holding both Syrians and Palestinians.” Of course, isolated interviews with politically active refugees are not sufficient to capture the prevailing sentiment of the Syrian refugee population as a whole. Still, interviews such as these, along with Palestinians’ extensively documented involvement in the uprising on the side of the opposition, provide a compelling ethnographic account of the affective dimension of their integration into pre-conflict Syrian society.

The early legal integration of the Palestinian refugees of Syria (PRS) and the concomitant rise in their socioeconomic fortunes in the proceeding years allowed certain elements of the refugee population to identify with the domestic aspirations of their Syrian neighbors, despite their official status as refugees and the pull of a competing Palestinian national identity.

(Dis)integration

However, the Syrian Civil War has resulted in a rapid and expansive deterioration in the material conditions of Palestinian refugees in Syria, as it has for broad swaths of the country’s population. Significantly however, the refugee community faces an additional threat in a post-conflict environment that Syrian nationals do not: the possibility of being unable to reintegrate into society at pre-conflict levels.

As Laurie Brand theorized in her study of Palestinians in Syria, it was the Syrian economy’s capacity to absorb Palestinian refugees without causing undue dislocations for the country’s citizens that facilitated much of their early integration. Relatedly, she notes that in times of poor economic performance, Syrian nationals would accuse Palestinians of having taken Syrian jobs, and predicts that further economic distress could accelerate this trend.

According to the Syrian Center for Policy Research, by the end of 2012, Syrian economic losses are presumed to have eclipsed $48 billion. This represents an economic loss equal to 81.7 percent of the country’s 2010 GDP. For the same period, the economy is estimated to have shed 1.5 million jobs, and the unemployment rate has surged from 10.6 percent to 34.9 percent.

Such a development is ominous for the Palestinian refugee population, which will not only find it more difficult to obtain work in a post-conflict environment, but also faces the possibility of discrimination and ostracism as a result of the economic collapse. The Assad regime’s initial attempts to portray the refugee community as a foreign instigator already indicate the possibilities of further marginalization in a post-conflict society.

Compounding the refugees’ economic difficulties, Syria has experienced massive inflation since the war’s inception, with a bevy of basic food and clothing items having increased in price from 50-70 percent, while gas and electricity prices have nearly doubled. Fafo’s report attributed much of Syria’s refugees’ economic advantage to the relatively low price of consumer goods in Syria, in contrast to other refugee host countries, a condition that has now all but vanished.

Moreover, as conditions in Syria continue to deteriorate, the PRS are increasingly dependent on international aid, particularly from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The total proportion of Palestinian refugees in Syria in need of humanitarian aid has skyrocketed. While only six percent of refugees received aid in the form of direct goods before the uprising, UNRWA estimated that in April of 2013, more than 400,000 thousand refugees, more than 80 percent of the total population, require such assistance.

To date, the UN agency has distributed food and non-food items to over 143,000 refugees in Syria, and is about to conclude a cash distribution plan to provide 6,000 Syrian pounds to 420,000 refugees by the end of August. UNRWA also notes that 235,000 PRS have become displaced, although it has been able to accommodate only about 7,300 in UNRWA shelters within Syria. Thus, the Palestinian refugees of Syria have become reliant on the largesse of international donors to maintain a substantially reduced standard of living, a striking contrast to their previous economic independence and success.

Conclusion

The Syrian Civil War has been a political and humanitarian disaster for all of Syria’s disparate communities and groups. The country is currently divided between rebel-held territory and areas where the government maintains authority, with broad swaths in between subject to violent battles for control. Sectarian tensions have flared, and the presence of foreign elements backing particular constituencies has further entrenched already potent divisions in Syrian society. Undoubtedly, reestablishing a politically and socially integrated polity in a post-Assad era will prove an extraordinarily difficult task.

However, owing to the economic, social, and political factors described above, the reintegration of Syria’s Palestinian refugees presents an even more challenging dilemma. The collapse of the Syrian economy has eliminated much of the economic advantage that Palestinians enjoyed in comparison to other host countries, and the economy may not be able to accommodate the proportion of refugees it did after their 1948 arrival. And as past periods of economic decline have demonstrated, competition from Palestinians for jobs may again result in social tension.

Moreover, the PRS are in a uniquely vulnerable position as refugees, unable to participate in the electoral process and thus more effectively demand official remedies to help restore their previous socioeconomic position. Regrettably, this civil war has transformed the case of Palestinian refugees in Syria from one of the issue’s more positive incarnations into one of its most tragic.

*[This article was originally published by Jadaliyya.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment