Despite Kejriwal’s loss of public support, the AAP brings new ideas and fresh energy to Indian politics.

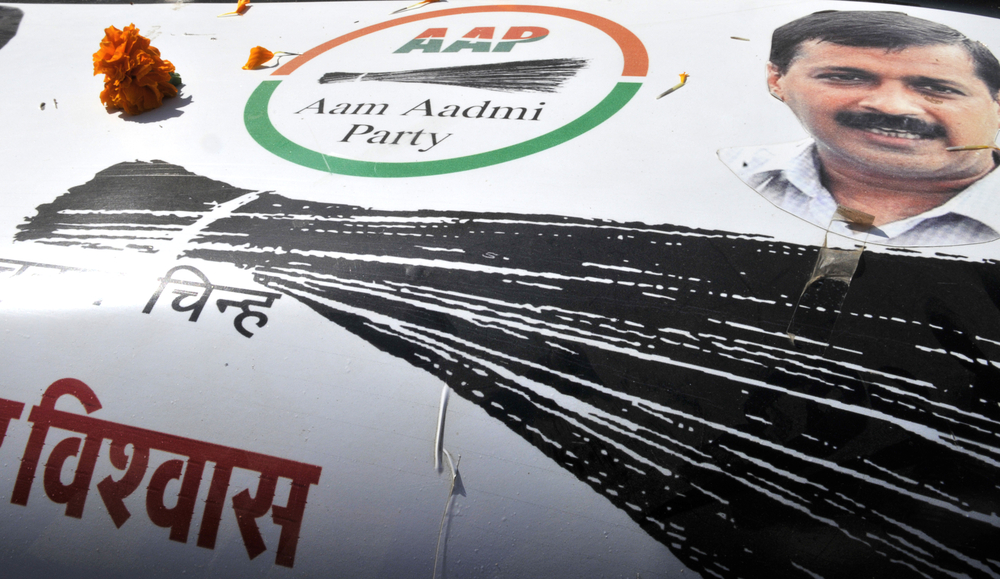

It is said that good things come to those who wait. In the case of Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), this was true till December 2013. The party won 28 seats, surprising everyone to form the government in Delhi.

The AAP has suffered some serious setbacks since. Kejriwal resigned from the chief minister’s post in 49 days over the Lokpal Bill. The party contested elections to the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of parliament, but won a mere four seats in Punjab. Some commentators stated that the AAP is facing doom.

These predictions are too premature. The AAP has the potential to be a strong alternative to parties like Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). However, a rapid shift in the AAP’s agenda prior to the general elections hurt its image. The party shifted its anticorruption agenda to an anti-BJP one, joining the Congress in opposing Narendra Modi.

Blunders Galore by Arvind Kejriwal

Kejriwal established the AAP in 2012, in the aftermath of a countrywide anticorruption wave. He had a clear objective: to build the AAP in Delhi and become a serious contender for the Delhi Assembly elections.

Things started going haywire once he became the chief minister. His tenure was marked by a series of protests and dharnas (sit-ins). It seemed that Kejriwal had intentionally shifted his gaze from governance to taking on the central government. Kejriwal went to the extent of joining a dharna to demand action against police officers who disobeyed Delhi Law Minister Somnath Bharti in the Khirki Extension raid. The protests were inconsequential, however, they did disrupt daily life in Delhi. The government itself was in limbo. This did not go down well with voters, who wanted governance and not theatrics.

Kejriwal’s resignation was a ploy to show that he did not care about being chief minister. People, especially the middle- and upper-classes, believed he resigned to contest the Indian general elections. They also felt he was not serious about fighting corruption and delivering better governance.

Its focus on grassroots democracy has a growing constituency, especially in urban areas. Focusing on fundamentals and building the party’s organization in other parts of India will help the AAP to survive and thrive.

Kejriwal quit as Delhi chief minister, thinking he had enough support to contest at the national level. This was a strategic error. First, the AAP did not have a presence in other parts of India. Second, his theatrics had undermined his credibility. Third, the AAP lost focus of what it wanted to do.

Kejriwal’s Missed Opportunities

Kejriwal missed the opportunity to introduce his unique bottom-up model of democracy when he resigned as Delhi’s chief minister. The model aims to diffuse power and responsibilities through Gram Sabhas (for villages) and Mohalla Sabhas (for cities and towns). Citizens are to have a greater say in solving issues that affect them. Kejriwal’s model is a serious attempt to reduce, if not do away with, the role played by bureaucrats in administration. According to him: “We replaced the British collector with an Indian. We kept all the paraphernalia of the British government as it is: its arrogance, its un-approachability, its mentality of being a ruler.”

India’s administrative system is in need of serious reforms. Presently, the complex rules and procedures often put people off. Out of desperation, people end up bribing concerned officials to get their work done. The second Administrative Reforms Commission in 2005 gave recommendations for good governance. The commission described participation of people in decision making as one of the characteristics of good governance. However, the commission stated that the participation can be indirect through “legitimate intermediate institutions.”

Kejriwal’s model, on the other hand, stresses on direct participation by people to voice their grievances and needs. This model will certainly pose its share of problems. For instance, involving several people may cause delays in implementation of essential projects. Yet Kejriwal’s model has the potential to make politics and governance more inclusive.

The AAP also missed the opportunity to build its presence in other urban areas of India. A party’s physical presence among the people often decides its electoral success. This was aptly demonstrated in Mumbai. The party fielded heavyweights from the city but did not win a single seat. Kejriwal also visited Mumbai just once as part of his campaign.

Mumbai is undergoing its own political transition. The Congress-Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) alliance was decimated by the Shiv Sena-BJP combination due to a strong anti-incumbency sentiment. Second, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) could not repeat its performance of 2009. This is relevant because, in 2009, the MNS ate into the Shiv Sena-BJP votes, and shifted the tide in favor of the Congress-NCP. This time, Shiv Sena claimed three out of the six seats in Mumbai, and the BJP secured the rest. Kejriwal has the opportunity to build the AAP’s presence in the city and fill the void created by the Congress-NCP’s rout.

One way to do so is to focus on a grave problem facing the city. Mumbai is home to the rich and also has several slums. One 2012 report stated that slums in Mumbai have gone up by 40% since 1995. Several houses in these slums have split air conditioners and satellite television connections, but no access to toilets or basic sanitation. According to Sharmila Murthy, a Mumbai slum called Kaula Bandar found that only 0.1% of residents have access to piped drinking water, only 3% have access to a private (that is, non-shared) toilet, and 14% practice open defecation. In the more upscale area of Malabar Hill, 6,000 people share 52 toilets, making it approximately 115 people per toilet. Similarly, Mumbai’s local trains also have inadequate toilets.

The AAP did not get a single seat in Mumbai in the general elections. Nevertheless, the AAP can take up this issue and mobilize the populace to solve this problem. Kejriwal stated that his party was committed to build 200,000 public toilets in Delhi. In the case of Mumbai, the AAP could initiate campaigns to ensure that the concerned authorities deliver the necessary infrastructure.

The AAP’s Outlook

It is early to assert that the AAP has politically reached the end of the road. However, the party has suffered several setbacks because of its recent decisions. Voters appreciate a clear political and socioeconomic agenda and a roadmap to implement it. The promises Kejriwal made prior to the Delhi Assembly elections impressed voters.

However, he failed to keep his promises. His tenure as the Delhi chief minister was high on theatrics and low on substance. Inevitably, Kejriwal lost public support and his resignation from the post was the last straw for voters.

Yet the AAP brings new ideas and a fresh energy to Indian politics. Its focus on grassroots democracy has a growing constituency, especially in urban areas. Focusing on fundamentals and building the party’s organization in other parts of India, especially in cities like Mumbai, will help the AAP to survive and thrive.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

1 comment

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Arvind

May 30, 2014

Great article and author deserves is analytical and insightful