In the fight for sovereignty in the South China Sea, The Philippines hold many economic, historical and political ties to the disputed region.

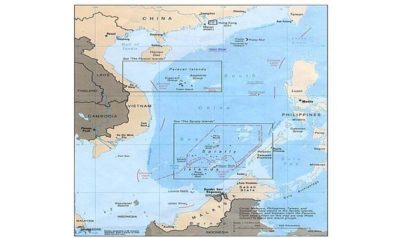

Throughout history, The Philippines has laid claim to the islands surrounding its maritime borders. As an archipelago, The Philippines considers these islands as strategic points for national defense and a symbol of sovereignty. Many are also rich in natural resources and support key economic activity, like fishing. Both the Spratly and Paracel islands in the South China Sea have been subjects of major dispute for a decade, and the implications of this discussion on the geopolitical and social sphere have been great. The faux pas generated by a lack of resolution on this conflict have caused critics to question the Philippine government’s ability to argue for its claims in front of the international community. However, from an economic, historical, and geopolitical standpoint, The Philippines should continue the fight for jurisdiction over the islands. It should be clarified that the argument here is not to add the South China Sea Islands as Philippine territory, but to protect the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) rights. All possible resolutions to the dispute should be diplomatic and must be careful to respect the views of other nations.

Historical and Legal Rights

The Philippines, as an archipelago, is governed by the archipelagic doctrine of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This doctrine states that an archipelago is considered as a single unit, and that the waters around the islands of the archipelago form part of the internal waters of the state and is subject to its exclusive sovereignty. The Philippine archipelago is regarded as an integrated unit instead of just 7,107 islands. The Philippine constitution now boasts provisions of the said doctrine to further define its territorial boundaries. The legal grounds of a nation’s claim are key to finding a resolution for the conflict. Under the UNCLOS, a nation with sovereignty over an island can claim a surrounding 12-nautical mile territorial sea. It must be noted, however, that while only a small portion of the Spratly and Paracel Islands can be considered part of Philippine territory, the Philippine 200-nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) encompasses a large portion of the area. The EEZ gives the owner country the right to protect and exploit the natural resources in the area it covers. Most nations, including The Philippines, understand that the islands of the South China Sea cannot simply be claimed as territory due to proximity (EEZ and territory are mutually exclusive); yet, these nations value these uninhabited islands for more than just the combined thirteen km2 land mass.

Throughout the 20th century, The Philippines has consistently asserted its claims to the Spratly islands and many other territories in the South China Sea within its EEZ. In 1946, Vice President Elpidio Quirino claimed the Spratlys on behalf of the Philippine government. In 1978, President Ferdinand Marcos issued a formal proclamation declaring ownership of the islands in the Spratlys, which was renamed the Kalayaan (Freedom) Island Group. The proclamation below was the basis for the Philippine claim over a majority of the South China Sea Islands:

"[The Philippines takes claim of the Kalayaan Group of islands] by virtue of their proximity and as part of the continental margin of the Philippine archipelago"; that "they do not legally belong to any state or nation, but by reason of history; indispensable need, and effective occupation and control established in accordance with international law [we control the islands]."

In 1995, President Fidel Ramos re-articulated the Philippine position regarding the Spratlys issue, stating that all islands and waters in the Spratlys belonged to the Philippines and were under its sovereignty. Both China and Vietnam put forward similar claims; these countries’ encroachments into the Philippine EEZ are strong indicators of their intent to capture the islands for their economic and military value. However, the pure historical bases of these countries’ claims contain many inaccuracies that weaken their respective claims. Vietnam continues to assert the claims of historical sovereignty over the disputed area despite it going beyond the 200 nautical miles allotment. In 2009, the Vietnamese government submitted to the UN an official expansion of its continental shelf into their “East Sea” (the South China Sea). China’s somewhat ambiguous “nine-dotted line” policy includes 90% of the South China Sea which includes the Paracel and the Spratly islands. This government policy is founded on maps as old as 1914, endorsed by the Kuomintang in 1947 and later by the Communist government; since 1949, China has backed up its claims with a strong military presence in the Paracel and Spratly islands, which they controlled after routing the Vietnamese naval forces in 1974 and in 1988. One fundamental reason for the lack of clarity is that China is only a signatory to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS); if Beijing’s claims were to be defined in accordance to this treaty, it would expose the government to harsh criticism. It is possible that Beijing’s continued support of the vague jurisdiction of the nine-dotted line is an explicit show of force by the ruling Communist Party. According to a Washington DC-based China foreign policy expert, the ambiguity is intentional and serves China’s domestic purposes of satisfying nationalist public opinion and preserving government legitimacy. The nine-dashed line, for all its historical worth, maximizes and even expands Beijing’s territorial scope, though it is difficult to justify under international law.

Economic Activity and Tradeoffs

The South China Sea supports many key economic activities in the region and though economic activity is limited to commercial fishing, each of the contending nations would like to hold the exclusive rights for starting commercial exploitation and development. This has led to various minor military skirmishes between the rival states, the detention of fishermen, and diplomatic rows over the past decades. For The Philippines, the establishment and full protection of its EEZ rights will go a long way towards helping its growing economy; the Filipino people will not only gain safe passage through a key trading zone, but may also access the reefs for tourism purposes and develop multi-million dollar mining operations. The mining and tourism industries in the EEZs have been extremely important in enticing and infusing FDIs (Foreign Direct Investments) into the Philippine economy through multinational companies. The economic significance of the region is so great that Beijing ordered its civilian patrol vessels to stop the Philippine coast guard from arresting Chinese fisherman working near Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands. However, the express jurisdiction over a waterway that provides approximately 10% of the global fisheries catch and about $5 trillion in ship-borne trade also lends itself to issues of national security.

Military Significance

The South China Sea is a located in a strategic area that may pose a threat to national security and to the economic trading capability of a certain nation should criminal or sabotage activities take place. The Spratly and Paracel Islands are along the world’s most heavily trafficked shipping lanes and hold untapped economic value and resources. The implications of fully controlling an EEZ is a possible reason why the Chinese and Vietnamese governments continue to contest the EEZ rights of The Philippines and assert their territorial claims on the Spratly and Paracel Islands and the Scarborough Shoal. Nations with uncontested authority over an EEZ may, to an extent, treat the zone as its “territory” and may therefore exercise security control and measures to discourage any foreign entities from entering. Though The Philippines is entitled to the South China Sea EEZ, many nations consider the economic and military significance of the zone too important to give any one nation the exclusive rights to establish a monopoly on trade routes and initiate the development of rich oil deposits. China, in particular, has been wary of other nations seeking to challenge its consistent naval dominance in the disputed area. Beijing has sent paramilitary patrol boats to bolster its military presence in a portion of the Philippine EEZ, which includes Scarborough Shoal, in response to the strategic “pivot” of the United States towards Asia to counter China’s growing power. The dispute over the region was heightened in the wake of Philippine-American exercises near the West Philippine Sea, a time when China to publically reiterated its right to defend its “maritime borders” with military force (i.e. 100 Chinese vessels, including four government patrol ships). Attempts by the Philippine Navy to chase illegal Chinese fishing operations from the EEZ have proved difficult; in the early months of 2012, a Philippine warship was engaged in a standoff with Chinese surveillance ships after trying to arrest Chinese fishermen. The sensitive issue of Chinese national security is not limited to The Philippines, as Vietnam announced in 2011 that Chinese vessels had cut the cables of a Vietnamese gas research ship.

Since 1955, The Philippines has considered the Spratly Islands and its accompanying territories of “vital proximity” to the country as an integral part of its foreign policy. But the question remains: What will our leaders do with China growing more and more aggressive in the region? The Philippine EEZ must be protected from Chinese military and commercial encroachment and to do so effectively, it must gain the approval and full backing of the international community. A well-protected Philippine EEZ is not so much about establishing a joint Philippine-US naval operation, but about preventing a relentless Chinese expansionist policy disguised within the nine-dotted line and the issue of national security. Though the Chinese perspective has to be considered in the bigger picture of the South China Sea, its hardline methods have been unwarranted. The current territorial skirmish with China is not just an incident of bilateral nature, but also an indicator of graver things to come. Defense analysts even assume that South China Sea may be the site of a future battleground of the 21st Century, and any continuing conflict can aversely affect the interests of 620 million people in Southeast Asia and 1.3 billion people in China. The Philippine islands themselves may be severely threatened if a strong foreign nation, such as China, were to wrest control of the EEZ.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer's editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment