While both Greece and Spain experience similar social and fiscal strains, the far right in Spain is failing to gain the momentum currently enjoyed by Greek extremist parties.

Over the past two decades, Southern European societies have undergone profound social and cultural transformations due to a deepening of European integration, large-scale immigration, and other processes associated with globalization. While welcomed by some, the new forms of ethnic and religious diversity, and the challenges to traditional institutions and values generated by these developments have elicited unease among others. Yet only in certain contexts have extreme-right parties managed to capitalize on this unease to achieve significant electoral gains.

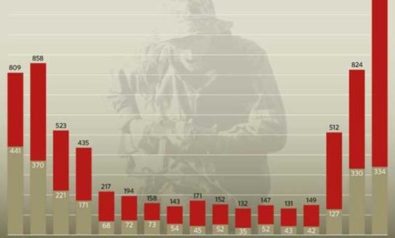

In Greece, Golden Dawn swept onto the political scene during the 2012 national elections, winning nearly 7% of the popular vote and securing 18 seats in Parliament. While this was a historic breakthrough for a party that had failed to make headway at the national level since being officially recognized in 1993, its success was not without precedent. Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS), a less extreme far right party, had previously attained 10 parliamentary seats in 2007 and 15 in 2009. The accomplishments of LAOS and Golden Dawn have shown that the extreme right is once again an important player in Greek politics after decades of stagnation following the country’s transition to democracy in 1974. In Spain, by contrast, no extreme-right party has been able to attain national representation in recent years, despite seemingly propitious circumstances.

Explaining why the extreme right has fared better in Greece than in Spain is far from simple. Spain shares many of the conditions that would seem to favor the success of parties comparable to LAOS or Golden Dawn. Between 1999 and 2008, Spain had one of the highest immigration rates in Europe, with the number of foreign nationals increasing from 750,000 to nearly 5.3 million. This exponential rise in immigration preceded a deep economic crisis that has left nearly a quarter of the country’s active population and half of its youth unemployed. If we also consider that Spaniards have one of the lowest secondary education attainment rates in Europe, it is surprising that no anti-immigrant, ultra-nationalist, or neo-fascist party has made significant electoral gains beyond the municipal level.

Part of the explanation for the distinct fortunes of extreme-right parties in Greece and Spain lies in the degree of competition they have faced from more moderate conservative parties. Greece’s main conservative party, New Democracy (ND), has had difficulty maintaining the support of more radical segments of the Greek Right, especially since the early 2000s. This has been due largely to the positions it has taken on several highly politicized international and domestic issues and events.

In particular, ND’s ambiguous stance on the UN’s plan to reunite Cyprus in 2004, as well as its pragmatic approach to dealing with the Macedonia naming dispute, enabled LAOS to bolster its image as the only credible party willing to unconditionally defend Greek national interests abroad. LAOS also benefitted from a controversy that occurred in the spring of 2007 over a school textbook, which it, along with the Orthodox Church and other conservative voices criticized for presenting an unpatriotic version of Greek history that minimized Ottoman and Turkish oppression. Although ND eventually gave in to pressures to withdraw the textbook, it did so only after appointing a new Minister of Education upon its re-election later that year. The previous minister, Marietta Yiannakou, had refused to withdraw the textbook, aggravating nationalists on the Right. This controversy was central to LAOS’ initial ascent into Parliament in the fall of 2007.

More recently, ND’s decision to support the implementation of two memoranda promising austerity reforms in return for EU and IMF bailout packages fed into Golden Dawn’s ability to capitalize on growing concerns regarding the retrenchment of the welfare state and the loss of Greek sovereignty due to international pressures. LAOS, it should be noted, backed the memoranda as well, at least initially, likely accounting for why many of its supporters shifted their allegiance to Golden Dawn during the 2012 election. Golden Dawn has also taken advantage of public backlash against immigration, particularly in central Athens and other urban areas, by staging anti-immigrant rallies and assembling vigilante gangs that harass and assault immigrants. Many, including segments of the police, have welcomed its actions as necessary in light of the government’s failure to protect the interests and wellbeing of Greek citizens.

Unlike ND, Spain’s Partido Popular (PP) has been successful in maintaining the confidence of voters on the far right of the political spectrum by strategically aligning itself with their views on several key matters. For one, the PP has shown its support for a unified Spain through its unequivocal opposition to the aspirations of Catalan and Basque nationalists for greater autonomy. It has also advanced tough rhetoric and policies on illegal immigration. After attaining an absolute majority in 2000, the PP enacted legislation that abolished irregular immigrants’ right to freely organize and strike, restricted access to education and legal services, and limited opportunities for legalization and family reunification. More recently, it took measures to restrict irregular immigrants’ access to Spain’s public health system. And, finally, the PP has been assertive in protecting traditional Catholic institutions and values through opposing Socialist reforms which provided for the legalization of gay marriage, relaxation of restrictions on abortion and divorce, and creation of an obligatory course on civic education that was criticized by conservatives for being part of a secularizing agenda.

The PP’s stance on these issues has made it difficult for extreme-right parties to carve a clear niche within Spain’s political landscape. Voters sympathetic to extreme-right perspectives are generally content with the PP’s positioning on matters of concern to them. Although the number of such voters is not terribly large (between 2.5% and 6% of the population), surveys conducted since the 1990s by the Center for Sociological Research show that roughly 90% support the PP. It is worth noting that Plataforma per Catalunya, the most successful extreme-right party in Spain at present, has been able to make substantial gains at the municipal level, in part, because the PP’s hostility toward Catalan nationalism has diminished its support in the region. In most of Spain, however, the PP has suffocated its competitors on the extreme right.

The greater success of extreme-right parties in Greece than in Spain is also related to the power of nationalist discourses and symbols to mobilize potential supporters in each country. According to political scientist Adamantia Pollis, Greek identity “can be understood as an organic whole in which Greek Orthodoxy, the éthnos, and the state are a unity.” Greeks take great pride in their ancient heritage and the pivotal role that it has played in the development of Western civilization. Although Greek culture has since been influenced by several different traditions, non-Hellenic and non-Orthodox elements are commonly minimized within narratives that present the nation as culturally homogeneous and temporally continuous.

The strong and unified sense of “We” among those native to Greece has made it hard for ethnic and religious “others” to claim a place and find acceptance within Greek society. Since the early 2000s, surveys have consistently shown that Greeks exhibit the highest level of xenophobia in Europe. To be sure, national identity is not the only factor contributing to this trend. For historical reasons, Greece bears a complicated relationship with Albania and other neighboring countries from which it receives immigrants, and its geopolitical location at the frontier between Europe and the Balkans has contributed to illegal border-crossings. The clustering of immigrants in specific urban neighborhoods, moreover, has heightened competition and feelings of civic insecurity. But nationalist rhetoric has played an important role in shaping how Greeks have interpreted, and reacted to, the changes associated with immigration and ethno-religious diversification. Such rhetoric has proven to be a highly effective resource for extreme-right parties to draw upon when appealing to voters’ interests and emotions.

In Spain, by contrast, nationalist discourses have a much weaker capacity to mobilize the populace. This is due, in part, to the coexistence of multiple national communities within the Spanish state, a reality which has made national identity more fragmented and contested than in Greece. Arguably more important, however, are the negative associations that highly charged appeals to Spanish nationalism conjure as a result of their similarity to the rhetoric espoused by Franco during his oppressive dictatorship.

While in power, Franco aggressively promoted political centralization and social uniformity through repressing all forms of cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity that did not cohere with his narrow conception of Spanish identity as unified and Catholic. When he died in 1975, Spaniards were eager to begin a new chapter in their nation’s history. Fearing a re-division of the country along traditional ideological lines, the process of democratic transition was characterized, above all, by a spirit of compromise and national reconciliation. After 36 years of dictatorship, the populace was weary of extremist rhetoric reminiscent of ¨National-Catholicism” and other elements of Franquist ideology.

Still today, nationalist discourses that call for a renewal of traditional, radically Catholic identity and the suppression of internal diversity have little appeal among the electorate. Nevertheless, extreme-right parties such as Democracia Nacional, Alernativa Española, and Falange Española have stubbornly clung to these issues and persist in placing them at the center of their social and political programs. The failure of the extreme right to innovate ideologically and separate itself from Franco’s unpopular legacy has been central to its continued marginalization.

Over the past decade, some parties have begun to change course by fashioning themselves after Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National and other populist parties that have had success in Northern Europe. In doing so, they have placed greater emphasis on contemporary concerns related to Islam, illegal immigration, crime, and insecurity. Plataforma per Catalunya, for instance, has been able to make gains at the municipal level through supporting local anti-mosque campaigns and legislation prohibiting face veils in public spaces. At the same time, it has strategically opted not to take a clear position on the question of national identity so as not to alienate voters on either side of the Catalan / Spanish divide. Its anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric has centered instead on the pitfalls of uncontrolled immigration and the importance of protecting broadly defined European and Western values. This has enabled it to partially avoid the allergic reaction that many Spaniards have to exclusionary ultra-nationalist rhetoric.

The relative success of extreme-right parties in Greece and Spain has been influenced by the degree of competition they face from more moderate conservative parties, as well as the distinctive capacity of nationalist discourses to mobilize potential supporters in each country. Should the PP suffer a major decline in popularity comparable to that suffered by ND due to perceptions that it is mismanaging the economic crisis, it is conceivable that a number of its supporters would defect to extreme-right parties. The success of the extreme right in Spain, however, will ultimately depend on its ability to innovate ideologically and to present a credible alternative to the policies and programs offered by mainstream parties. Fortunately for those who do not wish to see this happen, there is no party that appears capable of achieving this at present.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment