Those involved with the ongoing environmental movement in China – like many of the country’s burgeoning social movements – are using various strategies to demand one of democracy’s preconditions: the rule of law.

by Spike Nowak

Social movements against the government’s practices are gathering momentum throughout China. The one-child policy is openly being questioned, frequent protests are erupting over land acquisitions, factory workers are rioting over poor working conditions, and China’s social media is giving citizens a new avenue to voice their outrage against corruption in the government.

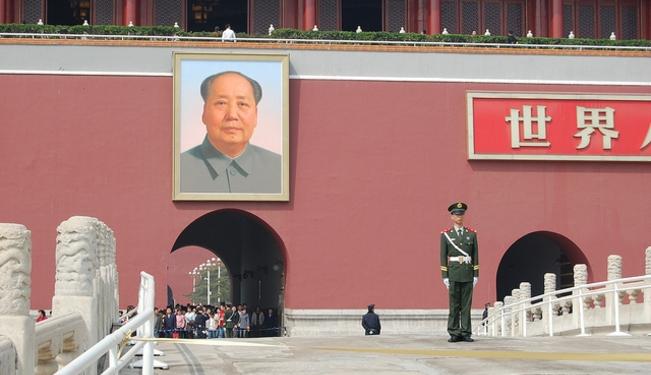

As China’s next generation of leaders prepares to take the reins of a rapidly changing country, Beijing can no longer pursue unbridled economic growth while ignoring its environmental consequences. Across the Middle Kingdom, citizens are taking to the street and protesting – sometimes violently – for a cleaner, healthier environment. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working on environmental issues are courting influential leaders in Beijing and pushing legal and political boundaries in order take a stand against the practices that have made China the world’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide.

The environmental movement in China, and the people involved in it, like many of the country’s other burgeoning social movements, are not calling for democracy. They are calling for the rule of law. At the local level, people are marching in protest against injustices that would not occur if China’s laws were fully enforced by local governments. At the central level, lawyers are attempting to force Beijing to obey its own laws.

Both parts of this two-tiered movement – a highly organised network of NGOs with close government relations, and frequent and isolated citizen-led protests at the local level – are striving for the same goal: the enforcement of already existing environmental laws and regulations. The main difference between the NGOs and the local protests are the methods they use – cooperative support versus confrontational demonstration.

Tsinghua University professor Sun Liping estimates the number of “mass incidents” (party-speak for protests) in China in 2010 at more than 180,000. Many of these were sparked by environmental concerns. Most of these demonstrations involve less than a few dozen people, but many of them are much larger and have managed to garner international attention. In July 2012, thousands of protesters marched in the city of Shifang in Sichuan province against plans to build a multi-million dollar copper plant in the city. The incident was widely reported in both domestic and international media. Three days after the protests began, the local government announced that it had scrapped plans to build the plant.

The Chinese government expends an enormous effort in keeping these incidents out of the public eye and, more importantly, isolated. According to China’s finance ministry, the country will spend $111bn on internal security in 2012. A report by the US Congressional Research Service estimated that in 2005 the Chinese government had 30,000 employees working on internet censorship and at preventing collective action; that number will likely have risen since.

Even China’s well-established environmental NGOs have not found a way to get around these barriers to coordination. All NGOs in China have to register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, which has the power to revoke an NGO’s legal status if it becomes “threatening” to the state. This severely restricts the ability of NGOs to organise their members and promote environmental causes, because in Beijing’s eyes there is a thin line between advocacy and provocation. In fact, established environmental NGOs rarely support local environmental protests even when government wrongdoing is egregiously evident, because doing so puts the organisation’s existence at stake.

However, this does not mean the NGOs working on environmental issues are powerless. The close relationship between the NGOs and the government allows the NGOs to negotiate the blurry legal and political boundary between what is acceptable and what is forbidden. This enables them to push those boundaries without stepping over the line and having their legal status revoked.

These close ties also allow the leaders of environmental NGOs to form alliances with government officials, which is of crucial importance in a county where knowing the right people makes all the difference. For example, Green Earth Volunteers (GEV) was able to use its contacts with the State Environmental Protection Agency to obtain environmental reports on a proposed project to build 13 hydroelectric dams on the Nu River in Yunnan province in south-west China. Another NGO, Friends of Nature, used its connections to convey GEV’s reports to influential government officials. In 2004 Premier Wen Jiabao temporarily halted work on the dams pending further research (however, plans to build the dams are part of China’s 12th five-year plan).

Close relationships with the central government also allow NGOs to confront and monitor local governments. The founder of the Center for Legal Assistance to Pollution Victims, Wang Canfa, believes that only 10% of China’s environmental laws and regulations are actually enforced.

With the state’s insufficient ability to oversee and enforce these laws, NGOs perform a watchdog-like function for officials in Beijing. When a Beijing-based NGO, the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, provided consumers with a list of known polluters and their products, a State Environmental Protection Agency official went so far as to say, “This is a brilliant boost to the enforcement of environmental laws.”

While NGOs work with the central government to help enforce China’s environmental regulations, protesters work against local governments and polluters to achieve similar ends. By pushing the state at two different levels, China’s environmental movement has joined China’s civil rights lawyers and dissidents, and China’s journalists and social media, in holding the government accountable.

Some China-watchers believe these various forms of discontent spell the end for the party’s autocratic reign and signal the beginning of a democratic China. But these beliefs are most likely misplaced. The end result of activism such as the two-tiered environmental movement will not be democracy. Instead, expect a more open society as Chinese citizens increase their demands for Beijing to actually implement laws.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer's editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment