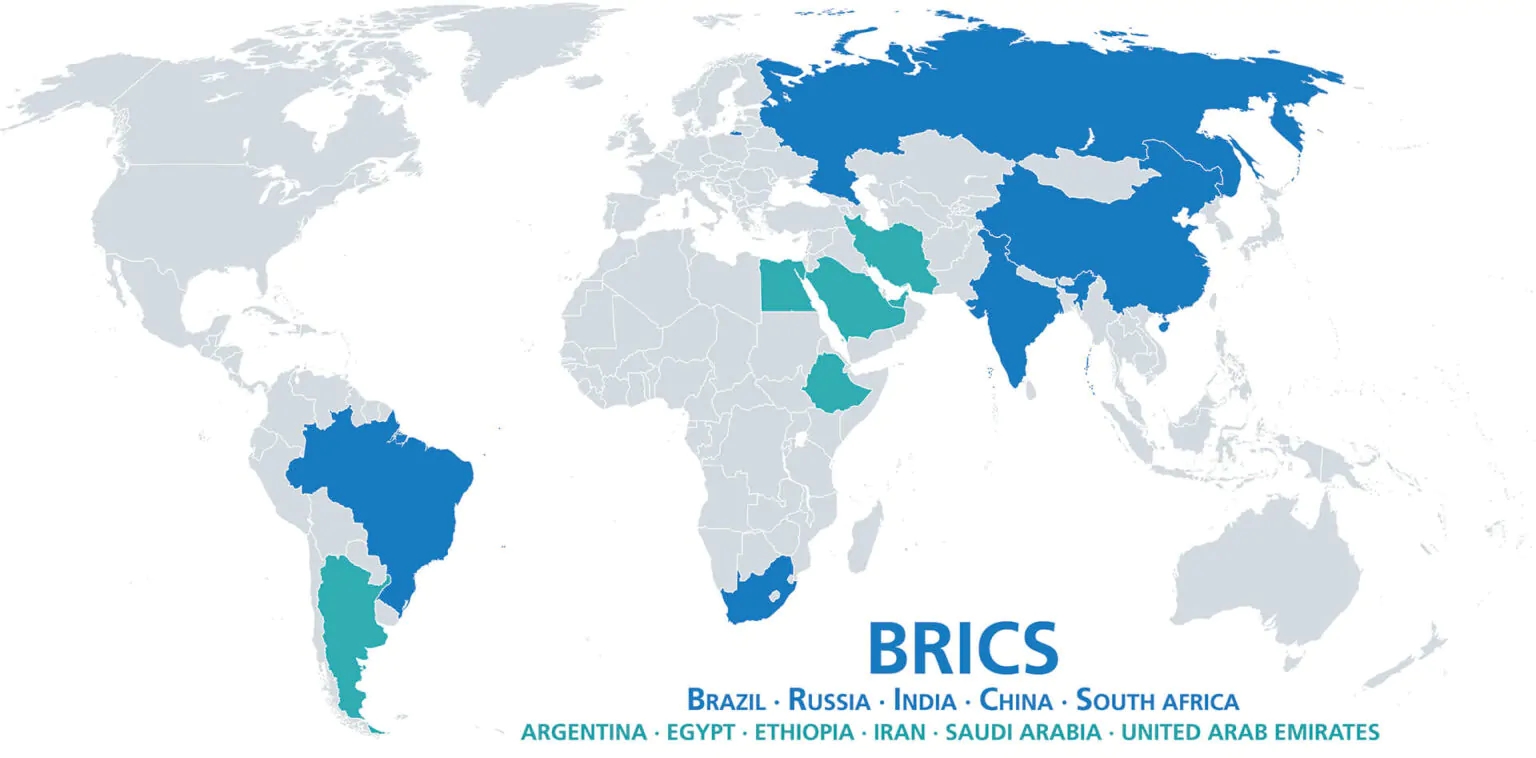

Russia, India and China formed RIC in 2001. Together with Brazil, they formed BRIC as an informal grouping in 2006. BRIC became a more formal entity and began holding annual summits in 2009. BRIC became BRICS when South Africa entered the grouping in 2010.

This year’s BRICS summit took place in South Africa from August 22–24. The most important outcome of the summit was the decision to expand the group. Six new members will join on January 1, 2024: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Argentina, Iran and Ethiopia. The original membership has just been doubled and this is a transformative outcome.

Originally, the RIC group was a response to the emergence of a unipolar world following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Then, the BRIC nations, four economically rising powers from three continents, shared an agenda. All four wanted to make the global order more democratic and equitable. When BRICS emerged, these powers wanted a greater role of developing countries in the new world order. At least three of the powers—India, Brazil and South Africa—sought to reform the postwar UN system, including its political and financial institutions. These emerging powers wanted to make the UN the centerpiece of a reinvigorated multilateralism.

End of the unipolar moment

This multilateral approach is becoming all the more important as the world exits its unipolar moment. Although the US remains the world’s leading political, military and economic power, it is no longer able to unilaterally dictate the rules of the international system. It failed to change the Middle Eastern balance of power in its favor by military intervention in the Iraq War or by indirect means during the Arab Spring. The disastrous end of its War on Terror, exemplified by the retreat from Afghanistan, has reduced its international primacy.

The US now sees the need to strengthen its alliances in Europe and Asia to retain its global preeminence. This includes the reinvigoration of NATO in Europe, as well as the alliances with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines in Asia.

The US is pulling the team together as new tensions—with potentially dire consequences for global peace and security—have pitted it against both Russia and China. It has succeeded in getting its European partners to throw their full support into a common effort against Russia and acknowledge that China is a systemic threat as well.

Furthermore, the US has used its financial power to the hilt to isolate Russia and cause its economic collapse. Washington has also openly subscribed to the idea of regime change in Russia, a peer nuclear power. It is not only Russia but also China that lies in American crosshairs. The US now sees China as its principal longer-term adversary and is taking aggressive steps to thwart China’s technological rise.

Tensions between great powers are straining the international system. Western sanctions on Russia have been draconian. In particular, the US has weaponized the dollar-based global financial system. The war in Ukraine has also had deeply disruptive effects on the supply of food, fertilizers and energy to developing countries. The equity of a global order based on rules set by the powerful is now in serious question. This order does not emanate from the collective will of the international community but is defined and determined by the West.

RIC, BRIC and then BRICS were all about multipolarity. These non-Western powers wanted a seat at the top table. Yet the dominant Western powers who champion human rights and democracy are not ready to cede control. In fact, the West imposes its agenda on these powers through championing supposedly “universal values” and does not want to give up its traditional hegemony. Naturally, the BRICS nations oppose this hegemony and want a redistribution of global power.

The West has been locked in a confrontation with Russia and China. Both these powers are responding by expanding BRICS. Hence, they have added six new members to the group. Some of them, like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Argentina have historic links with the US. Yet their joining BRICS demonstrates that they are willing to reduce their dependence on the West. These nations want a counterbalance to the US and seek a rebalancing of the global political and economic system, which does not have such punitive costs for transgression.

The inclusion of new members into the BRICS club is telling. Iran is already a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and close not only to China but also Russia. Iran has long been at loggerheads with the US and is subject to strong Western sanctions. Ethiopia is wracked by civil war and prolonged drought. Yet the country has made it to the club on the basis of its increasingly close relationship with China.

Clearly, the BRICS expansion sends a loud and clear signal. BRICS has welcomed powers that challenge the US and are close to China and Russia.

What were the criteria and what does BRICS expansion mean?

The entry of new members to the BRICS club raises a key question. What were the criteria?

Were they GDP size or growth prospects or population size or geographic location or regional influence or some combination of these factors? It turns out that, except for energy exporters Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the other new countries face serious economic problems. Egypt is the most populous Arab nation with the largest military in the region. Yet its economy is in an acute crisis. Argentina, the second-largest Latin American country, is in yet another economic crisis. Their addition does not exactly strengthen the BRICS club economically.

Importantly, no East or South Asian country joined the BRICS club. Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE lie in Asia but are part of the Middle East. Indonesia withdrew its candidacy at the last moment. It seems to be betting instead on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). BRICS is a geographically dispersed club while ASEAN is a cohesive organization with shared interests. External pressure by the US might also have played a role in Indonesia staying away from BRICS.

When it comes to African countries, Nigeria would have been a more credible addition than Ethiopia. However, the country did not apply for membership. Neither did Mexico. Algeria applied for membership but does not seem to have gotten in.

Clearly, the expansion of BRICS has been lopsided. Ethiopia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran are clustered together geographically. Only Argentina seems to stand out.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa declared: “We have tasked our Foreign Ministers to further develop the BRICS partner country model and a list of prospective partner countries and report by the next Summit.” Yet it is unclear what are the criteria for the expansion. It seems that new members have been admitted to the BRICS club on an ad hoc basis.

While expansion may boost multipolarity, it risks making the new BRICS+ club less cohesive. India and China have deep differences. Their militaries are in a standoff at the border. Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran are not exactly the best of friends. Brazil and Argentina are rivals.

Furthermore, the commitment of various countries to BRICS+ is far from solid. Under Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil had less commitment to BRICS than current president Lula da Silva. Tellingly, South Africa could not welcome Russian President Vladimir Putin because of its obligations to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Ramaphosa might wax lyrical about BRICS+, but his government is still constrained by Western-made law of The Hague-based ICC.

It remains to be seen how BRICS+ shapes up but it is clear that the addition of new members and prospects of further expansion are an indication of a growing, if inchoate, trend towards multipolarity.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment