The Obama administration should learn from America’s historic engagement with Syria following World War I.

On the afternoon of March 20, 1919, only months after the end of World War I, the leading statesmen of the allied powers gathered at the Paris residence of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The order of the day was the Middle East. For weeks, Britain and France squabbled over Syria. Each pursued diverging political and economic aims and, by March 20, the negotiations stalled.

Suddenly, it was US President Woodrow Wilson who broke the deadlock by offering a bold solution: An international commission should go to Syria to “elucidate the state of opinion” and “soil to be worked on” by any government. What ensued is the now-forgotten story of American involvement in the creation of modern Syria.

As the centenary of World War I approaches, valuable contributions to our understanding of the conflict’s European theater have saturated the market for popular history. Coverage of the war in the Middle East, by contrast, has recalibrated longstanding historical misconceptions. Pundits have rehashed the well-worn Lawrence of Arabia hagiography or reiterated how the Sykes-Picot agreement “carved up” the Ottoman Empire.

Wilson’s plan for a fact-finding mission to Syria in the spring of 1919 nearly altered the course of modern Middle Eastern history. It remains an instructive episode for policymakers struggling to respond to events in Syria almost a century later.

The agreement, signed between Britain and France in May 1916, planned to subdivide the Ottoman Middle East into Anglo-French governorates and indirect spheres of influence. By the end of the war, however, the agreement — despite popular myth — bore no relationship to emerging facts on the ground and ultimately had minimal impact on the post-war political settlement.

Syria and World War I

The First World War was a transformative moment for the Middle East but in ways that are misunderstood today. Wilson’s plan for a fact-finding mission to Syria in the spring of 1919 nearly altered the course of modern Middle Eastern history. It remains an instructive episode for policymakers struggling to respond to events in Syria almost a century later.

When war came to the Middle East in November 1914, it turned Syria upside down. British and French warships blockaded the Syrian coast, while Ottoman authorities shut down municipal services and rationed food. Natural disasters failed to spare Syria. Locusts swarmed the fabled orange groves around Jaffa in the spring of 1915. The result was a devastating humanitarian crisis. Fevers, cholera and typhus became commonplace, taking what some observers estimated was a 25% toll on the Syrian population.

Then, the American response to the Syrian humanitarian crisis was swift. American naval vessels in the eastern Mediterranean ferried refugees from the Syrian coast to safe harbors in Egypt, while US diplomats worked with local Ottoman officials to coordinate relief shipments. In the United States, a diverse group of church figures, industrialist-philanthropists and Syrian-Americans initiated a sweeping campaign to raise money and public awareness.

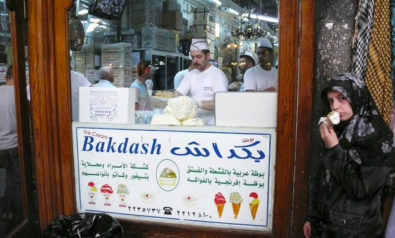

By summer 1916, the Rockefeller Foundation had earmarked $360,000 for relief in Syria, ranking second behind only Belgium as the largest recipient of Rockefeller aid. In Washington DC, society women operated donation booths and, in New York, the local Syrian community formed the “Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee” at 55 Broadway in Manhattan. Among its patrons were the Brooklyn-based Sahadi brothers, whose grocery store on Atlantic Avenue is today a reminder of the rich Syrian community that once thrived in Brooklyn Heights.

The same institutions promoting humanitarian aid merged into a formidable political pressure group by the end of the war. Its key figures, including Charles Crane — whose family-owned firm was a lucrative manufacturer of bathroom fixtures in early 20th century Chicago — traveled to Paris and pushed for American intervention in the ongoing dispute over Syria.

At the time, Britain had conquered much of the country but refused to evacuate its army from the Syrian interior. Based in Egypt, exiled Syrian moderates had begun to fall out with Britain and its tribal Arab clients. Through 1919, many Syrian nationalists remained skeptical of T.E. Lawrence’s ill-conceived plans to reconstitute the Arab-Muslim caliphate, linking Mecca with Damascus.

The King-Crane Commission and Foreign Invasion

Amid this backdrop of European deadlock and intra-Arab discord, Wilson’s commission planned to survey delegations of Syrian political leaders and report back to Paris. Overcoming intense Anglo-French opposition, the King-Crane Commission — it was named for its two commissioners, Charles Crane, and the president of Oberlin College, Henry King — sailed for Syria in early June 1919 and heard testimony from thousands of local dignitaries. Most favored a Syria free of colonial occupation and were reluctant to embrace Lawrence’s tribes or unite with Arabia.

Inauspiciously, when the commission report reached Paris, Wilson had already left for the US. By the time it surfaced at the White House, the president had collapsed from exhaustion following his nationwide speaking tour in support of the League of Nations.

Meanwhile, in Paris, the fallout from the commission for a time stifled the Anglo-French colonial plans to divide Syria. This would occur only when France, driven by a rapacious colonial lobby, desperately invaded in July 1920, crushing a provisional Arab government in Damascus. Had Wilson remained in Paris, he might have exploited American political and financial leverage to pursue the King-Crane commission’s recommendations and stave off a foreign invasion.

The Obama administration must now turn unequivocally to the one theater of the crisis where it can still make a difference: easing the humanitarian catastrophe.

The French colonial system that went into effect after the war privileged minorities and politically connected notables at the expense of forging representative institutions. The colonial authorities also pursued a hyper-centralized government in a region where local political groups — community associations, merchants and tribes — had traditionally enjoyed wide-ranging prerogatives.

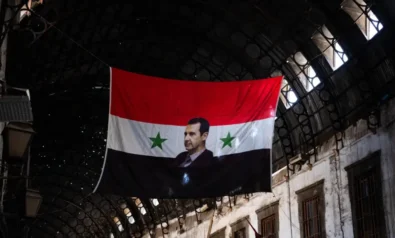

This non-representative and overly centralized system persisted through the mandate years and was largely appropriated by the Ba’ath party and Assad family.

Lessons for Today

The first American foray into Syrian politics in 1919 was stillborn but its lessons are clear. During the war, American policymakers had prioritized humanitarian assistance over regime change in Syria. When the war ended, US policy was consistent. It opposed a colonial settlement and promoted a fact-finding mission to support the wishes of local Syrians. It did not become an enabler of outside powers, either Britain, France or Islamists with minimal credibility on the Arab street, and did not set “red lines” that were politically impossible to enforce.

Following Syrian independence, the country was enveloped into the Cold War struggle between the US and Soviet Union to shape the balance of power in the region. Syria was seen as a proxy of Soviet interests in the Middle East, and US policy was colored by America’s fraught relationship toward Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt — which maintained a close alliance with Syria through much of the Cold War.

US foreign policy was now the product of fast-changing regional and global pressures. It was no longer consistent, open to Syrian moderates, and in tune with local political and social trends in the country itself.

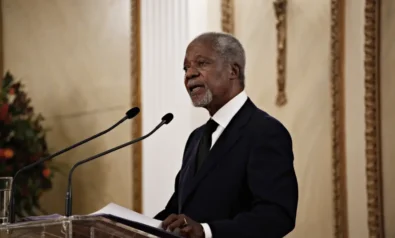

The legacy of America’s recent engagement with Syria over the past four years is still murkier and more tragic. When a political solution to the current crisis was most feasible, in June 2012 at the height of the Kofi Annan-led peace initiative, American officials sabotaged the negotiations.

On paper endorsing the ceasefire, in reality Washington had begun coordinating support for the rebels, giving a green light for Gulf Arab states to arm the opposition and embolden its extremists. This was a crucial inflection point. The flow of Gulf arms and finance to Syria aggravated what was fast becoming a sectarian war. It alienated Syrian moderates and irreversibly hardened the position of the Assad regime.

The Obama administration must now turn unequivocally to the one theater of the crisis where it can still make a difference: easing the humanitarian catastrophe. Shirking this opportunity, the US will remain a party to the destruction of Syria while its civil-war grinds on beyond the foreseeable future.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

Although your article is interesting it would be good to hear what you think the US should do to ease the humanitarian crisis. Just sounds very vague that’s all.