The GCC deal presents possibly the most realistic short term resolution to the Yemeni quagmire. It lessens the chance of civil war that would set Yemen back by decades. Nevertheless, it does not meet the demands of the vast majority of those who started the revolution.

In the royal surroundings of one of the many al-Saud palaces in Riyadh, President Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen signed the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) initiative on November 23, effectively signing away his presidency.

The Gulf initiative calls for Saleh to pass on his powers to his deputy, Abd-Rabbo Mansur Hadi, and then for Yemen to hold presidential elections after an optimistic three-month period.

Decisively, the deal gives the President and his family members immunity from future prosecution, a move that has angered the youth movement that took to the streets of Yemen in February.

Although it is far too optimistic to say that this is the end of the political crisis that has plagued Yemen this year, there are some definite positives that have emerged out of this deal.

First, after months of violence and an increase in fighting between rival military factions, the deal greatly reduces the chances of civil war in the poorest Arab state. Saleh’s sons and nephews control large parts of the Yemeni armed forces; the GCC deal brings the hope that they may be removed from their positions without a fight.

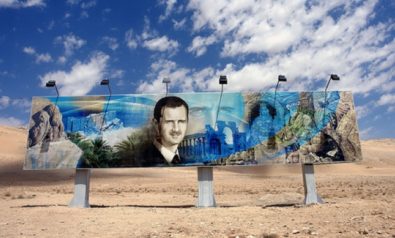

Second, the deal highlights the positive role the international community can play. Attempts to find a way out of the crisis have been very laborious, but gradually the US and the EU were able to get their act together and pressurise Saleh into signing. It is very likely that the main reason he did sign was the asset freeze and travel ban hanging over his head. Saleh was never a Muammar Gaddafi once he realised the international community was not bluffing he decided to sign the deal, preferring it to joining the ranks of Robert Mugabe and Bashar al Assad.

However, despite the probable immediate benefit of avoiding a disastrous civil war, there are several long-term problems that arise.

Many members of the youth movement, especially those who consider themselves ‘independent’ andnot affiliated with the official opposition parties, are completely against the GCC deal. This has been the case since April, after which then there has been a strong sentiment amongst these protesters that the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP) opposition grouping is effectively stealing the youth revolution. The independent youth have complained at times of being stifled by the JMP and by the defected First Armoured Division, and have even said that they are the reason why the revolution has taken so long.

The GCC deal may be particularly problematic in the future because of those associated with it, namely Saleh and the GCC itself. Saleh is a master of deception, and even now that he has signed, it is likely that he will try and find a way to lessen the effect of the deal. He may attempt to negotiate and ensure that his sons and other family members remain in their positions, effectively retaining the control of Saleh’s Sanhan sub-tribe. Saleh is back in Yemen, announcing a Presidential Pardon for offences committed during the political crisis, apart from the bomb attack against him. He seems to have forgotten that, officially, he has no powers. Preliminary reports concerning the make-up of the next cabinet say that the President’s son, Republican Guard head Ahmed Ali Saleh, is to be one of the Deputy Prime Ministers, and the Minister of Interior—not a particularly encouraging sign.

The GCC itself is a group of six autocratic monarchies, not particularly inspiring for Yemenis wishing to leave the era of authoritarianism. The strongest power in the regional alliance is Saudi Arabia, a country known for its often negative interventions in Yemen over the past decades. Does Saudi Arabia really want a democratic Yemen that could potentially inspire those within Saudi itself? More importantly, will it allow a strong Yemen, independent of Saudi control?

Has there ever been an instance of a group of effectively absolute monarchies overseeing a democratic transition?

The GCC deal presents possibly the most realistic short term resolution to the Yemeni predicament. It lessens the chance of civil war that would set Yemen back by decades. Nevertheless, it does not meet the demands of the vast majority of those who started the revolution, people who want the complete removal of an endemically corrupt regime. As events in Egypt currently show, those protesting in the Arab world do not seem likely to accept solutions that do not give them all of what they want. Revolution 2.0 may be on its way in Yemen—if Saleh does not manage to wriggle free, once again.

*[This article was originally published in the independent online magazine www.opendemocracy.net on December 5, 2011].

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment