Analysis on the changing face and role of Islam in Central Asia.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a significant portion of the attention devoted to post-Soviet Central Asia focused on the role that Islamic activism was likely to play in the politics of the region. After the systematic repression of the Soviet years, many feared that Central Asia’s ‘rediscovery’ of its Islamic identity would result in inexorable radicalisation. This prospect preoccupied Western leaders and came to define the political discourse of authoritarianism in the region. As a consequence of this, Islam became a critical element in the political rhetoric formulated by the international community and the Central Asian regimes in the 1990s and, most emphatically, in the post-9/11 years. Central to this rhetoric was the issue of external influences (originating alternatively in Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan) that were supposedly infiltrating Central Asia with destabilising intents. The containment of these influences became a key rationale behind the support extended by Western states to Central Asian authoritarianism, which often justified its brutal repression of alternative political groups by flagging the spectre of the “Islamic threat”. Critically, the manipulation of Islam emerged as a regular feature of the Central Asian political arena.

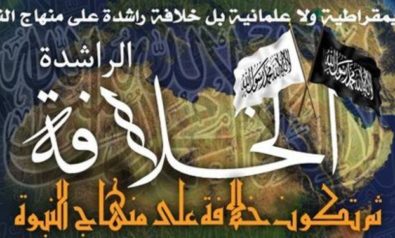

Twenty years after independence and a decade after the commencement of US-led military operations in Afghanistan, no caliphate has emerged in post-Soviet Central Asia, and Islamic activism has not acquired a prominent position in regional politics, which remains stridently authoritarian and largely uncontested. A cursory glance at the region’s religious dynamics seems therefore to reject earlier predictions about the revolutionary connotation of Islamic resurgence in Central Asia, confirming that the politics of repression did indeed pay dividends to the local regimes. A number of relatively recent events questioned the relevance of such analysis, which oversimplifies the complexity of Central Asia’s Islam – a force that managed, in the last few years, to abandon the corner where the regimes had relegated it. The dual logic of manipulation and control, in other words, failed to stop the radicalisation of Central Asian Islam.

This last proposition captures in full the intricate nature of the current relation between Islam and the state in Central Asia, which is increasingly defined by a significant disconnection between regimes’ intentions and the reality on the ground. Such disconnection led to a rupture between the persistence of oppression and the emergence of dissent. It is precisely there that the radicalisation of Islam in the region finds its raison d’être.

On the one hand, the regimes maintained a firm grip on Islamic activism. A combination of regulatory efforts and repressive initiatives ensured control over religious life in the region. The emergence of religious parties has been strictly monitored by the central governments. To date, Tajikistan’s Islamic Renaissance Party represents the only authorized Islamic political organisation operating in Central Asia. The logic of regime control also applied to the leadership of local Islam, as the Central Asian governments continued to appoint their respective grand muftis, following a practice consolidated in Soviet times. Local communities are regularly constrained in their exchanges with non-Central Asian Muslims. The governments closely monitor the activities of foreign preachers, while the pious practice of the hajj is often subjected to strict central control such as the cases of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan allowing only limited numbers of pilgrims to make the annual trip to Mecca. After the boom of the 1990s, the construction of new mosques evolved into a problematic issue for the Central Asian governments, which regularly attempted to block the emergence of non-authorised worship places throughout the region. The regimes often used legislative measures to contain the advancement of Islamic activism. For example, the Kazakhstani government introduced a 2011 law that requested the re-registration of every religious organisation operating in the country. As per the Central Asian norm, repression soon became a subsidiary element of monitoring policies: expressions of Islamic activism in opposition to the regimes rapidly came to be equated to manifestations of terrorism. This association, in the early 2000s, thwarted Islam in the region, and particularly in Uzbekistan, where terrorist trials have a 100% conviction rate.

Rigid control mechanisms nevertheless failed to contain the rise of political actors operating under the Islamic banner. As a consequence, Central Asia’s Islam is an emerging force, whose visibility has now crossed the borders of the Ferghana Valley – traditionally considered the hotbed of Islamic activism in the region. Islamic manifestations have transcended the more religious sphere and come to permeate the Central Asian political arena, both as legitimate contenders of and as violent antagonists to the incumbent regimes. In May 2011, Kazakhstan witnessed its first suicide bombing, which took place in the western city of Aqtobe. In the Kyrgyzstani election of October 2011, a presidential hopeful ran on an agenda that included one of the most characteristic (and clichéd) themes of antagonist Islam: the promotion of shari‘a law in the Kyrgyzstani political landscape. At the same time, Salafi interpretations of the Islamic belief system have reportedly acquired increasing popularity in Tajikistan’s most remote areas. Religious radicalisation has hence become a recurrent theme in the conversations held in the Central Asian street.

Remarkably, the recent resurgence of Central Asian Islam is not the intended outcome of the incessant action of external forces, although the influence of exogenous factors on the regional religious landscape ought not to be underestimated. Rather, it represents part of the responses that the local populations formulate in response to the dual politico-economic crises that affects the region. In this sense, the politicisation of Central Asian Islam came from within, as its rationale is deeply rooted in the popular perception of the region’s authoritarian politics and of its economic shortcomings. Just as they did in Algeria in the 1980s, Islamic organisations are filling the socio-economic void left by the state in the poorest strata of Central Asia’s society, combining financial assistance to the deprived with the diffusion of the Islamic message. At the same time, Islamic activism gathered popularity in wealthier and more educated demographics as it began to intercept part of the political dissent expressed by the Central Asian population. Economic grievances and reaction to authoritarianism are hence behind the most recent episodes of Islamic radicalisation in Central Asia.

It can be said that, after two decades of control and repression, the Central Asian regimes have finally got the Islam they deserved: antagonist, self-confident, and increasingly popular. Their systemic manipulation of religion – through which the leaders first overplayed the Islamic card to increase domestic support and then evoked the Islamic threat to promote internal repression – backfired with Islamic activism now timidly (and perhaps inexorably) emerging as an alternative political force throughout the region. This is not to say that Central Asia is on the verge of an Islamic revolution, as the regimes continue to enjoy a virtually unchallenged control over the domestic political landscape. Nevertheless, regime stability in the region appears now to be uncertain due to a combination of aging leadership (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and, to a lesser extent, Tajikistan) and shaky governance (Kyrgyzstan). In the medium term, this scenario might open some space for political contestation in the region. Should its radicalisation go further, Islamic activism might as well emerge as a key force amidst such instability.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment