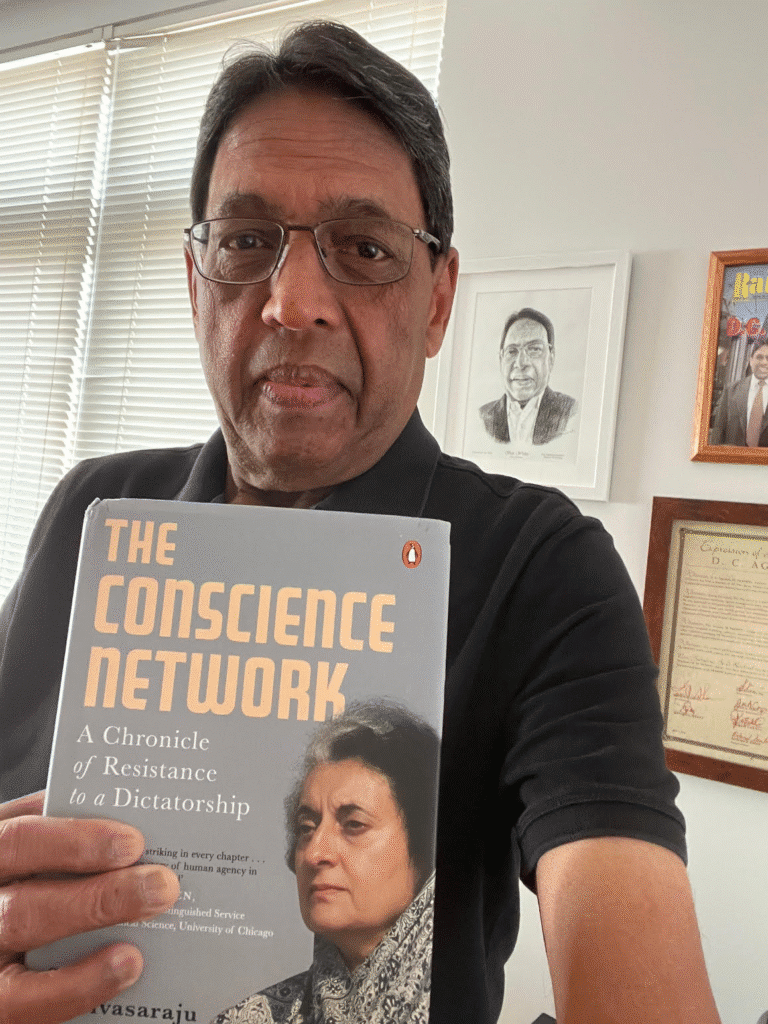

Rohan Khattar Singh, Fair Observer’s Video Producer & Social Media Manager, talks with DC Agrawal, an activist and urban transport consultant. Agrawal was one of the earliest Indian Americans to protest Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Emergency in 1975. Agrawal played a key role in founding Indians for Democracy (IFD), a movement of expatriates dedicated to restoring democratic rights in India. Over the years, he has also been involved in developmental organizations and contributed to the establishment of the New Jersey Transport Corporation.

In this conversation, Agrawal reflects on his activism during the Emergency, the challenges of mobilizing the Indian diaspora in America and the global significance of their efforts.

Indira Gandhi’s Emergency

Agrawal recalls June 25, 1975, as a watershed moment in Indian politics. On that day, Gandhi’s administration arrested opposition leaders, including Jayaprakash Narayan, and the prime minister declared an internal Emergency. She suspended civil liberties and imprisoned thousands. For Agrawal, who was already engaged in developmental causes, this moment underscored the fragility of democracy.

He places these events in context: America at the time was witnessing anti-Vietnam War protests, while Indians had only recently supported Gandhi during the Bangladesh Liberation War. India itself was still reeling from droughts and famine in the late 1960s, experiences Agrawal witnessed firsthand.

Protests in America

On June 30, 1975, just days after the Emergency was declared, Agrawal and his friends, including Anand Kumar — a close associate of Narayan — organized a protest outside the Indian Embassy in Washington, DC. Agrawal drove from Philadelphia to Maryland to join the organizers.

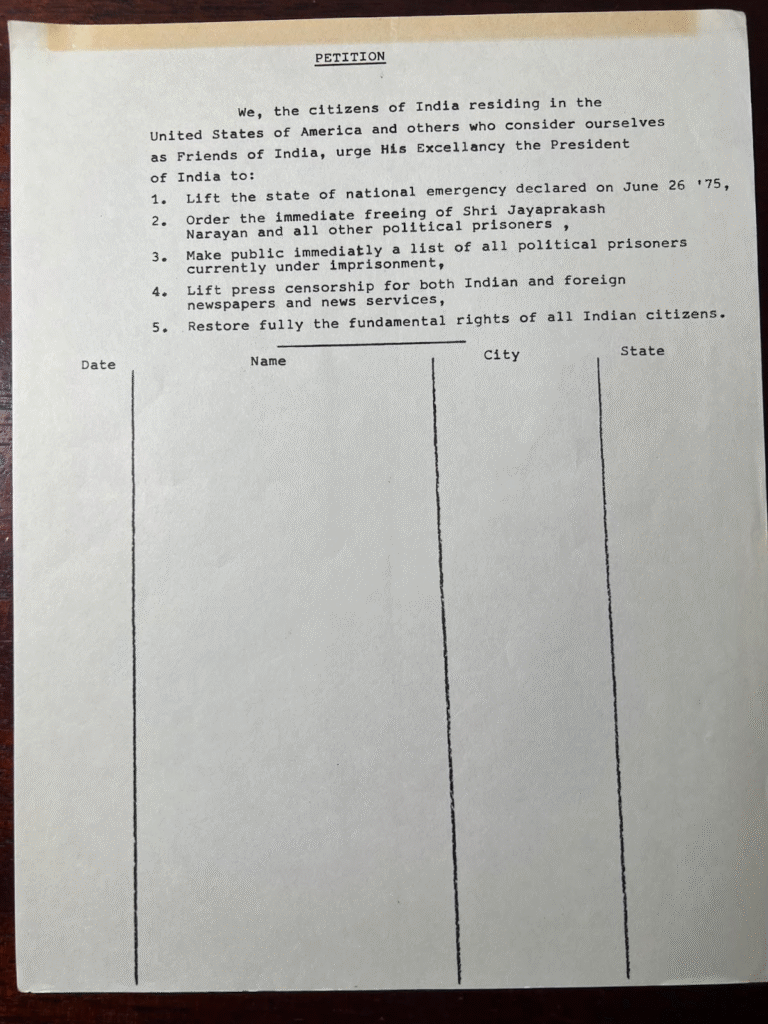

In the days leading up to the demonstration, they circulated petitions, collecting names and states of residence. Many were hesitant to provide full details. Those who did were, in Agrawal’s words, “fairly brave souls,” given the “fear complex” in the community.

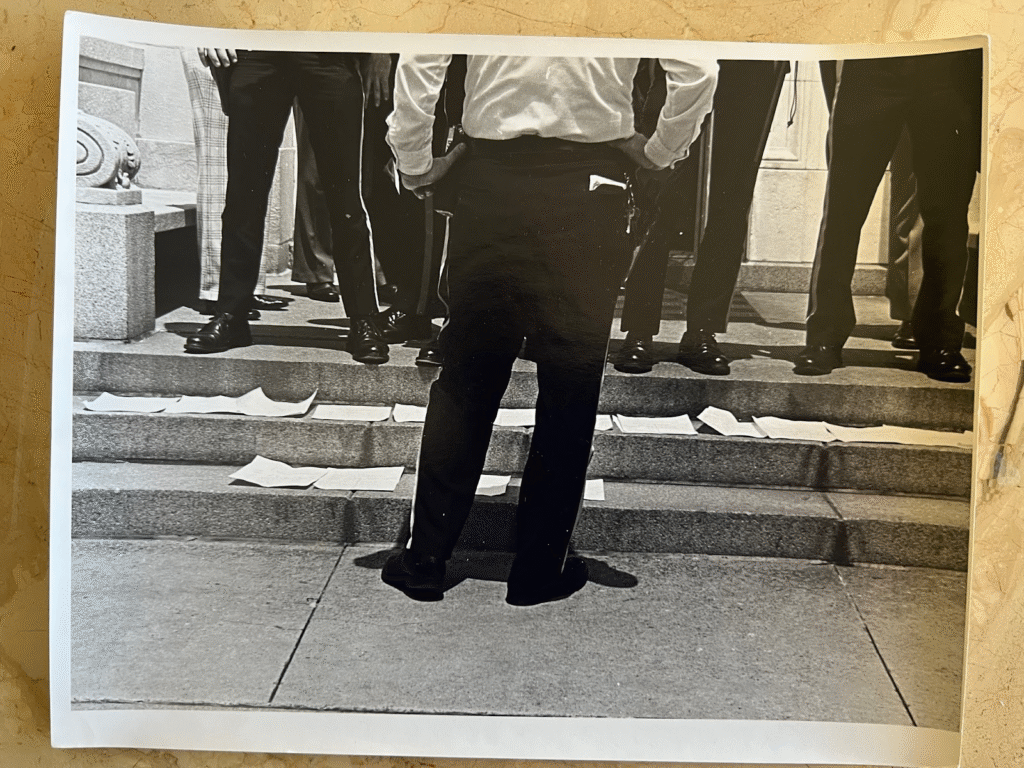

At the embassy, officials refused to accept the petitions. The protesters left them on the steps, where Agrawal, a photographer, captured a striking image: the petitions scattered on the ground beneath the boots of a heavy police presence summoned by the embassy. To him, the image symbolized how power structures resist dissent. It even reminded him of fascist imagery from Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s regime in World War II.

How Indian Americans united

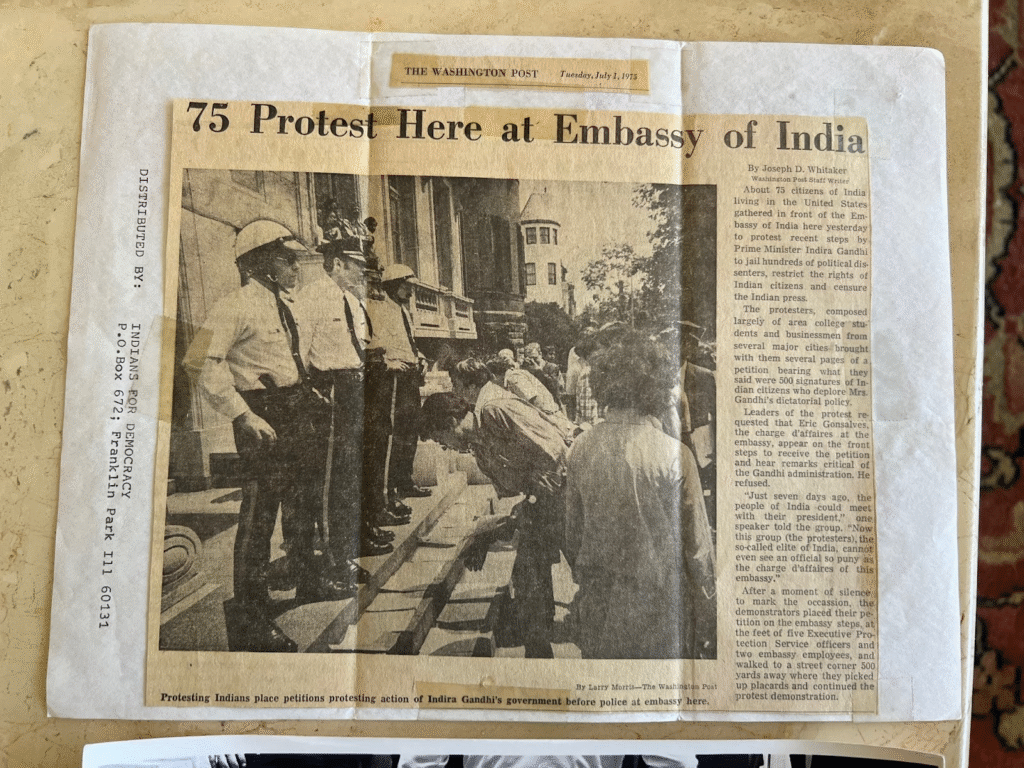

The following day, the Washington Post published photos of the protest in its newspapers. Soon after, the protesters held a press conference at the National Press Club, calling for the Emergency to be lifted, political prisoners freed and democratic rights restored.

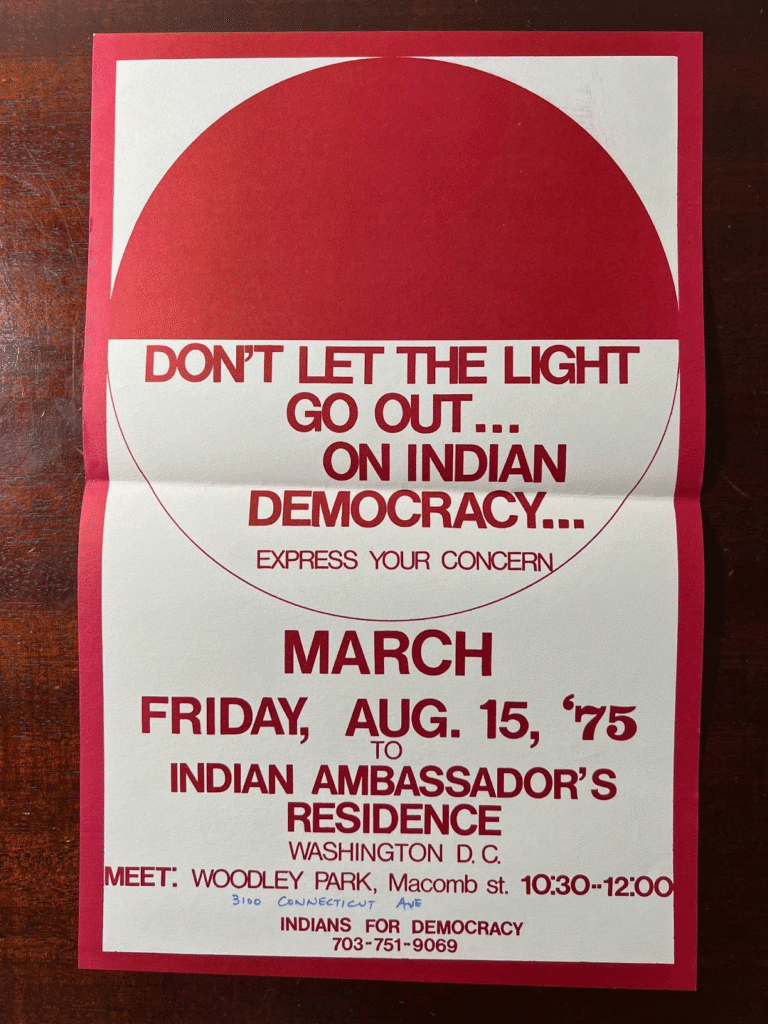

They continued with demonstrations on August 15 — India’s Independence Day — in front of the ambassador’s residence in Washington, at the Indian consulate in New York, and in Chicago. IFD also began publishing a newsletter: Indian Opinion.

Agrawal emphasizes that the group stayed “Gandhian in spirit,” deliberately non-partisan and focused on democracy rather than party politics. Their supporters came from across the spectrum — from Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) right-wingers and Jan Sangh to leftists — and tried to maintain neutrality.

Global media coverage

Without today’s communication tools, mobilization depended on cold-calling Indian names in phone books and organizing at Indian stores. They received mixed responses: Some hung up, some feared reprisals but donated money, while others quietly supported.

The Indian embassy, meanwhile, monitored activists, photographing them and even revoking passports. Kumar, a PhD student at the University of Chicago, had his government scholarship suspended, which drew headlines. Support also came from India Abroad, a new newspaper committed to covering censorship in India; Indian papers blacked out entire articles.

Initially, American media, including The New York Times, were sympathetic to Gandhi. They interpreted events through a Cold War lens. But credibility shifted when she postponed elections in 1976. Support from groups like the Quakers and the American Friends Service Committee, who were “friends of [Jawaharlal] Nehru and [Mahatma] Gandhi,” also boosted the movement. Major outlets like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Washington Post began covering the protests more seriously. Congressmen arranged hearings in Washington with testimony from Indian leaders such as Subramanian Swamy and Ram Jethmalani, supported by Senator Ted Kennedy’s office.

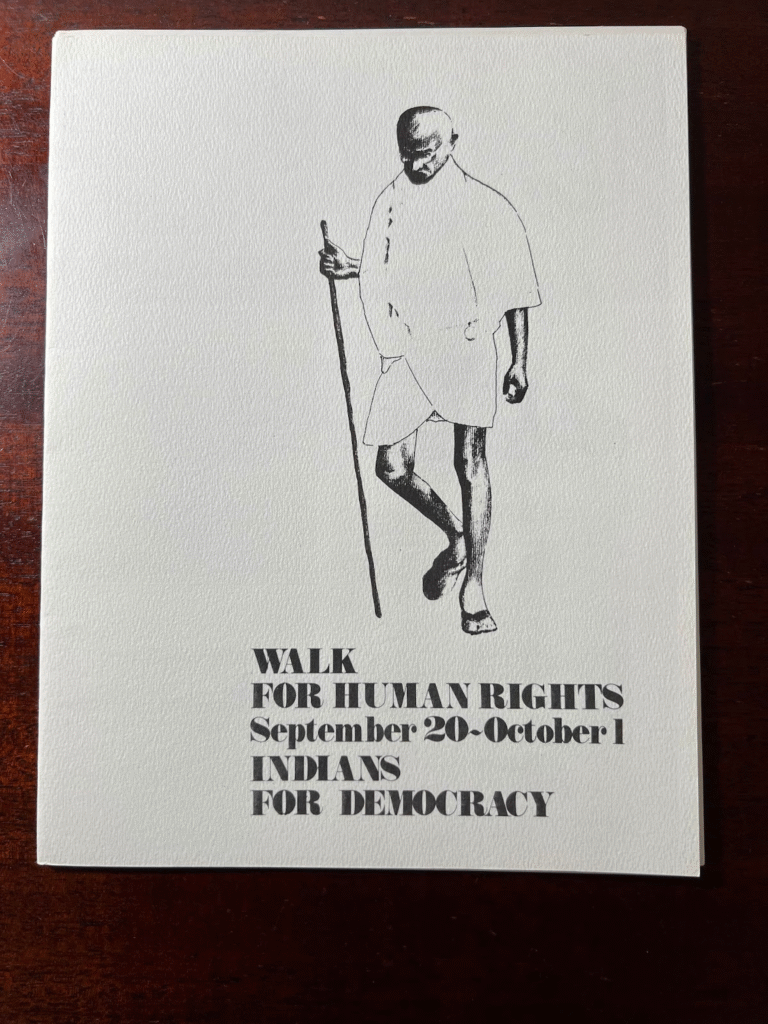

Walk for Human Rights

By the fall of 1976, the activists sought a bold, symbolic action. They launched the Walk for Human Rights from Independence Hall in Philadelphia to the United Nations in New York, ending deliberately on October 2 — Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday.

The Gandhian, non-violent march lasted ten days. It began with 30–40 people and consolidated into a committed group of about ten. The walkers stopped at several universities, including Temple University in Pennsylvania, Princeton University and Rutgers University in New Jersey, and Columbia University in New York. Here, they spoke about human and political rights.

Agrawal says the march increased their credibility both with the diaspora and with Indian officials. He later learned that Indian minister YB Chavan asked US President Gerald Ford to ban the demonstrations. Ford reportedly refused, affirming that America was a democracy.

For participants, the walk was cathartic. Agrawal believes it even pressured Gandhi, who cared deeply about her global image, to reconsider her position. He argues this contributed to the Emergency being lifted and elections being called in 1977.

The diaspora during Emergency

The Indian diaspora in America at the time was tiny — perhaps fewer than 100,000, concentrated in universities and a few cities. Most professionals avoided involvement, fearing repercussions for themselves or relatives in India. Students were more active, though some leftist groups criticized IFD’s Gandhian methods as “too docile.” Meanwhile, supporters of RSS and Jan Sangh pursued their own lobbying and fundraising, especially as many of their families were directly affected by arrests.

Agrawal reflects that even today, in moments of crisis, only a small minority of Indian Americans would get directly involved, while most would remain passive or offer private support.

Aftermath and legacy

The Emergency ended on March 21, 1977. The Indian government held elections later that year. Agrawal and his colleagues sent a detailed letter to the new prime minister, Morarji Desai, and Members of Parliament, urging reforms such as repealing the Maintenance of Internal Security Act and creating a Right to Information Act.

In October 1977, Agrawal became one of four activists invited to meet Desai and External Affairs Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Both leaders thanked them for their efforts. Agrawal remembers the meeting as gratifying, even if not all their proposals were adopted. For him, the experience confirmed the value of diaspora activism in defending India’s democratic traditions.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment