Dear FO° Reader,

The world has never changed as quickly and profoundly as it is now changing.

I spent the first two months of 2023 in India as a visiting professor at Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar. That was a major change for me, since I had not found myself in a formal teaching situation for at least three decades. I was invited to teach a course in geopolitics focused on a world order that was visibly shifting from unipolar to multipolar.

Those two months turned out to be an heady experience for several reasons. Working with students on geopolitics in India turned out to be the perfect occasion for adjusting my own geopolitical perception. After all, the most important feature of authentic “teaching” is the learning experience for the teacher. I made that point to my students in my introduction to the course.

But other things were going on. In 2022, the Fair Observer team had decided to embark on a project aimed at evolving towards a model of publication that increasingly integrated the notion of dialogue. We adopted the suggestion of one of a friend of the journal, Steve Elleman, who encouraged us to aim at becoming a “crucible of collaboration.”

It should be obvious that the model of expression for most media is monologue. That happens to be our historical and cultural reality. But monologue has its limits and risks. It encourages narcissism. It installs a competitive rather than a collaborative model. Western individualism has imbued us with the idea that self-expression is a sacred right. Collective understanding, according to the dominant liberal ideology, occurs only as a random statistical phenomenon or thanks to the invisible hand of the marketplace.

Throughout history, however, collective understanding has been possible thanks to our capacity for dialogue. Self-expression may be, and indeed must be, the starting point. That is why we at Fair Observer invite everyone to express themselves seriously on the questions that matter for them. But if self-expression alone becomes the goal, cultural anarchy and social disorder will ensue. On a major scale, we see that logic playing out today in all our democracies. The advent of social media is an obvious contributing factor, but it is not the cause.

How a word lost its meaning

In the modern Western educational tradition, our perception of the growth of our civilization takes as its essential starting point the “Athenian moment” that took place two and a half millennia ago. We learn at school that the resourceful Greeks — besides conducting internecine wars — spent their time doing two highly civilized things that remain important for us to this day. They bequeathed to us the idea of politics and philosophy.

Raphael, School of Athens

The Athenians invented democracy. And not just the idea of democracy — they actually practiced it. They also invented philosophy, a term that literally meant “the love of wisdom”: φίλος (philos), “love,” and σοφία (sophia), “wisdom.” I’ve always thought it a pity that the idea that emerges in our minds when we hear the word philosophy today is something like the “deep thoughts expressed by a great mind.” In contrast, the Athenians conceived it first of all as love, the basis of a relationship. Love (philos) is a selfless emotion that drives a person to fulfill a goal and create a connection. Wisdom, unlike knowledge, refers to the dynamic of establishing an understanding the world and relationship to the universe.

I maintain that, for anyone interested in the topic, the first philosophical act we need to engage in is a meditation on the word itself. This can be done as a simple thought experiment. Try to imagine what it might be for a first-year university student today to say: “Yeah, I’m thinking of majoring in the love of wisdom.”

How philosophers philosophized

In modern philosophy courses, we learn that philosophy emerged in essentially two phases. There were the pre-Socratics who set the stage, and then there were the three luminaries who wrote the script. The first of these latter three was Socrates, who never wrote a single word but spent his time in dialogue. The second was Plato, who, rather than exposing his brilliant ideas as finished products for others to ponder, imbibe and eventually repeat or gloss, transcribed the spontaneous dialogues Socrates engaged in Plato’s philosophy emerges as a process of elaboration of conflicting interpretations, not as a set of doctrines.

Then there was Aristotle, the most modern and academic of the three. We sometimes forget that almost all of the texts now attributed to Aristotle were composed from notes made by his students who had been in an ongoing dialogue with the master. They called Aristotle and his school “the Peripatetics” because he taught while “walking around” the grounds of his Lyceum in a permanent dialogue with his students.

The Athenian moment only lasted a couple of centuries. At some point in the intervening millennia the wisdom (σοφία) the Greeks so loved became codified in Europe as “knowledge” (scientia) which are quite different concepts. Students of philosophy became imbibers of written and already formulated knowledge. The ferment of dialogue disappeared. With the advance of our technologies, especially after the invention of the printing press and much later with our current digital technologies, the reproduction of already-formulated knowledge has dominated our understanding of what was once an act of love seeking to understand dynamically the structure and meaning of our universe.

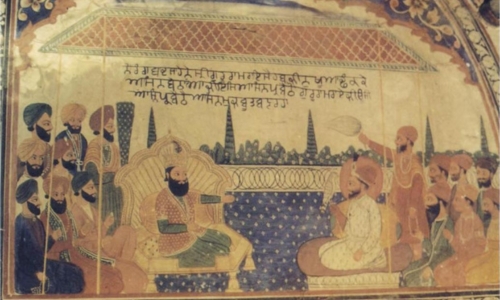

Mural of Guru Ram Rai in-conversation with Aurangzeb. Guru Ram Rai Darbar Sahib, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

Can we retrieve our talent for constructing understanding through dialogue? In a world that everyone recognizes to be evolving towards multipolarity, this has never been more necessary. Now that this same civilization has produced machines designed to produce artificially intelligent monologues for us, dialogue becomes even more important.

In my weekly column, Outside the Box, I attempt to create something like the authentic give-and-take of human dialogue with ChatGPT. In each column, I comment on the difficulty of the task. AI is not designed for dialogue, whereas we humans are.

The idea occurred to me that the challenge of engaging in dialogue with AI may be the best hope we have of rediscovering our own capacity for dialogue. That is why, at the end of my columns, I am now inviting readers to join the conversation. This is an open invitation. I want to hear from you, respond, engage and — like Plato with Socrates — transcribe and publish the result. We have created an email address specifically for that purpose.

Here is the concluding paragraph of last week’s Outside the Box:

We invite anyone who wishes to weigh in on this to share their thoughts with us at dialogue@fairobserver.com. We will publish your insights as part of an ongoing three-way dialogue we propose to develop between Fair Observer, ChatGPT and our readers.

We look forward to your contributions and to the wisdom we may collectively elaborate together.

Mes amitiés,

Peter Isackson

Chief Visionary Officer

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news must be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and editors cost money. So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

|