I have just finished reading a truly excellent book, which I recommend to anyone who is interested in the history of modern France. Penguin Books published Julian Jackson’s France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain this year.

The book describes the trial of Marshal Philippe Pétain, which took place only a few weeks after the war ended, and uses it to do two things: look back at the events that led to France’s humiliating defeat in 1940, and look forward to the present day to see how France remembers, and commemorates, its behavior between 1940 and 1945, especially vis-à-vis Jewish people.

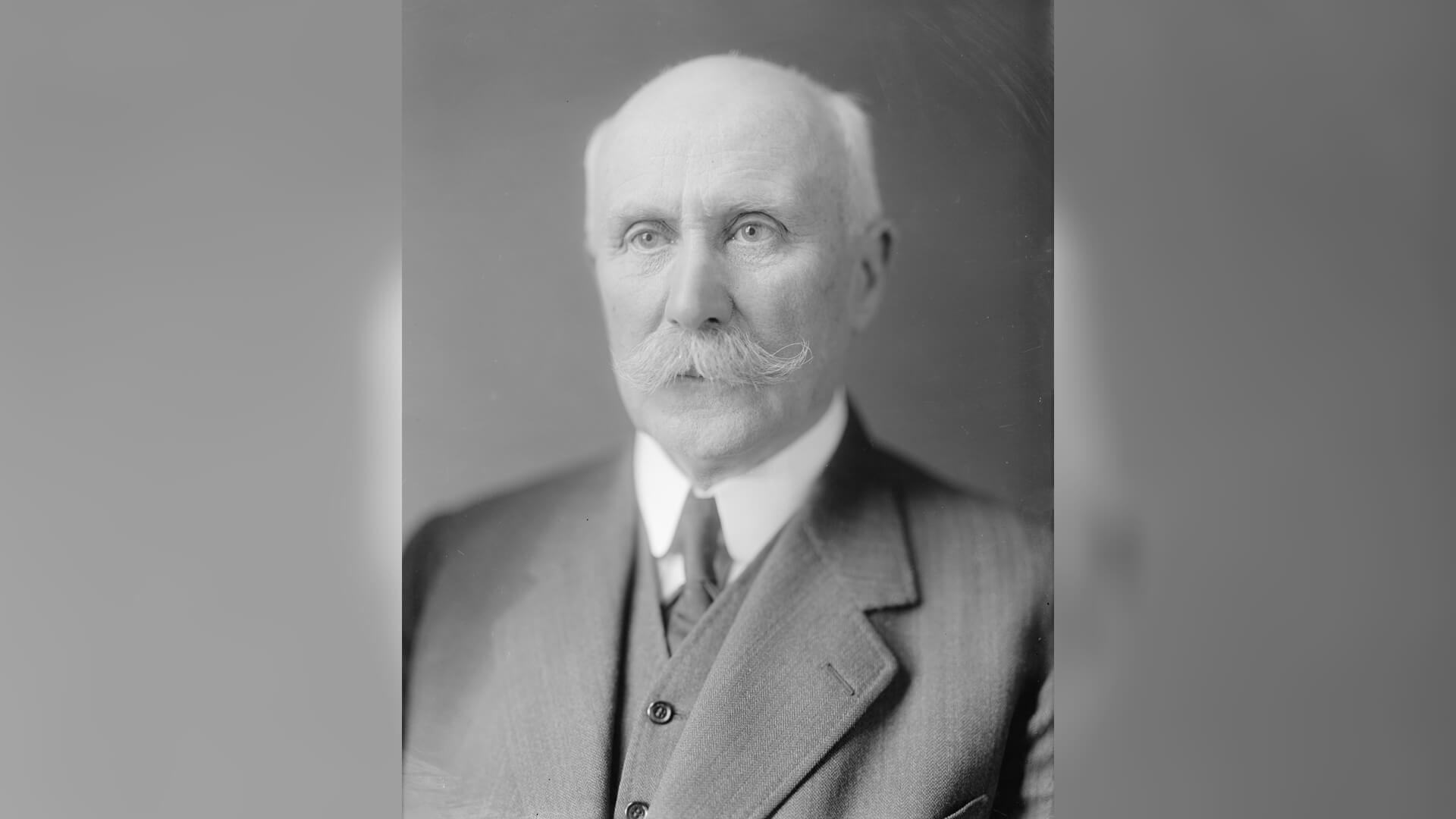

Pétain was the great French war hero of World War I, especially due to his leadership in the crucial Battle of Verdun in 1916. Through this, he had acquired a godlike status. By the 1930s, Pétain had long been retired from the army, and thus he had no responsibility for the strategic error of the French High Command that led to the defeat of May 1940. This error was sending the French Army deep into Belgium when Germany attacked that country, which created a gap in French defenses that allowed the Germans to encircle a large portion of the Allied armies from the rear in the vicinity of Dunkirk.

The consequences of this mistake discredited those who held office in France in the period immediately before the war. This included former prime ministers Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud. Both of these ex-prime ministers gave evidence in Pétain’s trial.

So did another ex-prime minister, Pierre Laval, who was later to be tried and executed for treason in 1945.

The author says that, for Laval, “no cause, however noble, could justify a war.” He had been prime minister in the 1930s and wanted reconciliation with Italy. During World War II, he said that he favored German victory, a matter on which Pétain wisely offered no opinion.

When the Germans surrendered in 1945, Laval escaped to Spain, but Franco did not want him. According to the author, Laval was then offered asylum by the Irish government, presumably on the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera’s instructions.

I have never read any exploration of this issue in books about de Valera. Laval could have proved an embarrassing guest for Ireland. In the event, Laval opted to return to France and face a trial which he must have known would sentence him to death rather than live peacefully in Ireland.

Pétain’s emergency leadership

Coming back to the dilemma faced by the French government in 1940, after the shock of the encirclement had worn off, the French army resisted the Germans bravely and effectively in central France. But the damage to public morale, caused by the initial defeat, was too deep.

Could the French Army have resisted long enough to retreat with their government to Algeria (technically part of France)?

Some of Pétain’s accusers argued that he should have taken this option and ordered the army to fight on rather than seek an armistice from the Germans. Others criticized him for not joining the Americans when they landed in North Africa in 1942. Instead, he authorized the French Army in North Africa to resist the Americans. Many interpreted this as treason.

How did Pétain come to be in charge in late 1940 and thus be in a position to make these choices?

The previous French government, headed by Reynaud, had retreated from Paris to Bordeaux after the initial defeat in May 1940. But it needed a new leader. It turned to Pétain, as an untainted national leader, to head a new government.

It was almost as if the politicians gathered in Bordeaux felt they needed the “Pétain magic” to restore France. This was the hope on the basis of which the National Assembly made Pétain head of state, soon with unlimited powers. It was never a viable project.

If Pétain had thought things through, he would never have lent himself to such a dubious and hopeless endeavor. His vanity got the better of him.

Even if Germany had won the war, and had come to terms with Britain, the prestige of Pétain would not have sufficed to wipe France’s humiliation away.

Trial of a once-hero

How informative were the proceedings at the trial?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that some issues were explored too much in the trial and that others deserved more attention.

A big part of the prosecution’s case was that Pétain had long been preparing himself for a French military defeat and plotting how to exploit defeat to grasp supreme power. There was no evidence to back this.

The issue that got too little attention in the trial, in light of what we now know, was the active involvement of the French police, and of the Vichy government, in the transportation of the Jews to the gas chambers.

Pétain’s defense team argued that the regime had spared many French people, including French Jews, from the horrors of direct German occupation by taking over the administration of a large portion of the interior of the country from 1940 to 1943 and that this saved lives.

There is statistical evidence to back this up. The survival rate of Jews in France, at the end of the war, was much higher than that of Jews in Poland and the Netherlands, which were directly occupied by the Germans and where virtually every Jew was wiped out.

Another issue that could have gotten more attention was the Munich Agreement with Hitler which sapped French morale.

Many of the themes evoked in this book are current today.

Grappling with the past

What is treason?

Is it treasonable to make the mistake of backing the loser?

Where is the line to be drawn between bad political judgment and treason? Where is the boundary between making a legitimate political judgment, and betraying a cause that is, or appears, lost?

What constitutes a war crime? That had not been defined at the time.

Who should be the jury in a trial like this? Pétain’s jury consisted of two halves: sitting National Assembly deputies and recently active members of the Resistance. This politicized the judicial system in a way that would not be allowed today.

Jackson’s book also explores the emotions of the French people in the aftermath of an acute crisis. France has emerged as a strong democracy despite the trauma.

For the record, Pétain was condemned to death at the end of the trial. But the jury anticipated, correctly, that Charles de Gaulle would commute the sentence. Pétain died peacefully some years later.

The great merit of the book is the human stories it tells so well, prompting the reader to ask how he or she would have reacted if faced with the same dilemmas.

[Anton Schauble edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment