The New York Times managed a particularly convincing scoop this week when it exposed a story of collusion with some pretty dramatic consequences, including the loss of thousands of innocent lives, all for the sake of corporate profit. This one is based on fact rather than the musing of the conspiracy theorists at The Times who have been pushing the narrative of Russiagate collusion for the past four years.

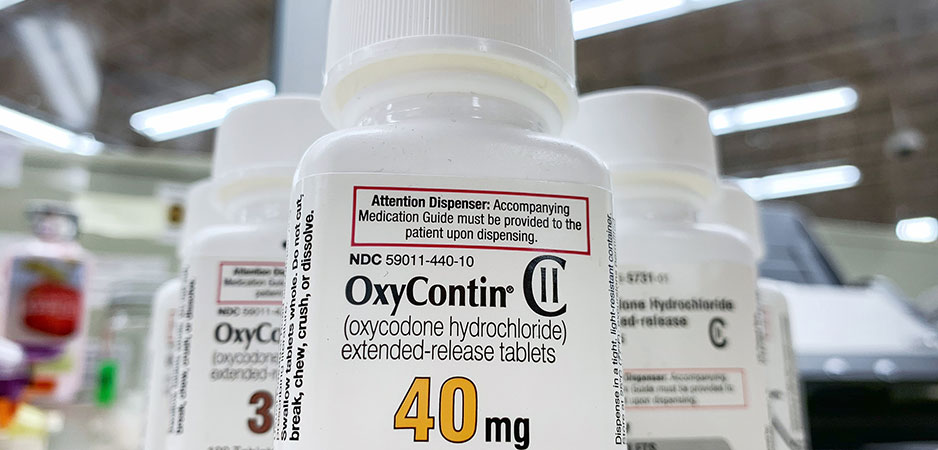

In an article titled “McKinsey Proposed Paying Pharmacy Companies Rebates for OxyContin Overdoses,” The Times journalists Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe expose the particularly shameful complicity between Purdue Pharma, which is owned by the Sackler family and achieved the height of notoriety by nearly single-handedly creating the ongoing opioid crisis in the US, and the world’s most famous and highly-respected management consultancy firm.

Joe Biden’s Revolving-Door Cabinet

The two companies worked together around a single well-focused objective: to make as much profit as possible from their addictive painkiller, OxyContin. When the government began invoking rules that might restrain the development of the marketplace, it was time to react: “The Sackler family saw those rules as a threat and, joining with McKinsey, made a plan to ‘band together’ with other opioid makers to push back, according to one email.”

Today’s Daily Devil’s Dictionary definition:

Band together:

Creatively collaborate in a way that includes hiding from public view the purpose and the effects of the collaboration.

Contextual Note

McKinsey would not have its exceptional reputation if its consultants weren’t so damn good at what they do for their clients. What do they do? They simply make sure that no opportunity is missed for their client to make money. If the client is already making money — which tends to be the case for anyone who can afford McKinsey’s services — then their mission will be to let no opportunity pass for them to make more money. Being consummate professionals, McKinsey’s consultants generally take care not to break the law but, laws being what they are — difficult to interpret and easy to massage in the hands of well-paid lawyers — there are many cases when breaking the law will only be a minor obstacle.

The article cites the celebrated author of the book “Winners Take All” Anand Giridharadas, who keeps track of how billionaires such as the Sackler family not only build and manage their businesses, but how they wield the power that their billions have dropped into their hands. Giridharadas happens to be a former McKinsey consultant, schooled in their methodology. After reviewing the documents unearthed by The Times authors, he commented: “This is the banality of evil, M.B.A. edition.”

Some may claim, as the Department of Justice did after evaluating Alex Acosta’s special treatment of Jeffrey Epstein, that this is just another example of “poor judgment.” Not Giridharadas, who cuts to the quick: “They knew what was going on. And they found a way to look past it, through it, around it, so as to answer the only questions they cared about: how to make the client money and, when the walls closed in, how to protect themselves.” Giridharadas signals that there are two crucial steps in the McKinsey method: working out the best way to make money (while keeping the method hidden from sight) and building the defense destined to shield their client (and themselves) from prosecution.

All might have gone well. But in the case of OxyContin, the drug turned out to be the goose that laid too many golden eggs. Those eggs turned out to be only gold-plated, emitting a nauseating stench from the inside when the number of overdoses reached such alarming proportions that the public and the media began noticing: In 2018, opioids were responsible for 46,802 fatalities, or nearly 70% of all drug overdose-related deaths in the United States. Concerning the value of the gold itself, $12 to 13 billion in profit is the round figure cited by Forbes. Forbes also calls it “a mystery how much money has been paid out to the family over the years.” Enough, in any case, to pay for McKinsey’s services.

Coincidentally, “Forbes estimated the Sackler family was worth $12.4 billion.” What are profits for, if not enriching beyond any reasonable threshold the owners of a business? The theorists of capitalism tell us that profits serve two purposes. The first is to improve and expand the vocation of businesses that supply needed services to the community. The second is to achieve greater efficiency in production. Excesses of profit then feed innovation by stimulating new investments.

The recent history of the workings of companies that generate billions of dollars of income shows that profits, especially deriving from excessive margins, now serve the primary purpose of defining the capitalists as members of a class that controls the economy and, ipso facto, the lives and behaviors of others. In the Sacklers’ case, it isn’t only the lives but, more significantly, the deaths of others — by the tens of thousands.

Historical Note

Business, financial and legal consultants have risen to the pinnacle of today’s economy, providing the key to unlocking the true potential of capitalism. They have become the equivalent of the frontal cortex of modern corporations, organisms that formerly existed to prosper harmoniously within their original environments but now exist for the sole purpose of achieving power.

According to Charles Darwin, any living organism, whether plant or animal, is programmed by evolution to interact with its environment in such a way as to ensure its survival and exploit its relative reproductive advantage. Organisms capable of reading their environment with the mobility to execute their survival strategy, which includes most of the animal kingdom, are mostly content to do whatever is required to appease an appetite for nourishment and respond to their immediate physical needs.

Once upon a time, traditional capitalists functioned according to the same principles. They focused on survival and achieving a favorable balance with their environment. Then, a couple of hundred years ago, something changed. Exceptional success within a new laissez-faire economic culture and the ability to reach a wide marketplace made it possible for some enterprising capitalists in the 19th century to see the practical advantage of becoming “robber barons” in the literal sense of the word. The Rockefellers, Carnegies and the JP Morgans created what amounted to a new ethic of triumphant capitalism that sought not survival and integration into the environment, but domination.

It was the spirit of the age. At the same time, European nations were moving beyond the humble ideal of autarchy to the colonialist ideal that permitted them to control supply chains, manage financial flux, diversify production and manipulate markets. The emergence of such complex needs spawned the vocation of business consultants, outsiders who felt fewer ethical restraints than business owners. This insider-outsider relationship made it possible to consider traditional social constraints and eventually even the legal constraints that society imposed as unnecessary distractions. That included what had long existed as a shared, although vague, sense of ethics or norms of interpersonal behavior. To achieve the power that monopolistic companies have achieved today required not only the creation of an insider-outsider brain of the corporation but also a transformation of the ethical sense shared by the societies within which they work. Most societies frown upon both the abuse of power and the principle itself of allowing so much accumulated power. That annoying feature had to be overcome.

This required transformation came into effect slowly over the past two hundred years. The liberation from traditional social constraints became nearly absolute by the end of the 20th century. It can be described as the transformation of the notion of solidarity, a principle that binds all human groups together and without which no society can function. The consumer society that emerged in the 20th century served to convince the masses of the utility of capitalism. It clearly put the individual’s interests above those of the group, effectively obscuring the needs of the group.

More simply put, transactional solidarity has supplanted social solidarity. The “banding together” of Sackler and McKinsey provides a perfect example of transactional solidarity. But so does the arrangement by which Joe Biden’s cabinet picks can be “legally and ethically bound” to secrecy about their business relations. Banding works. The idea of belonging to a band evokes two contrary associations in most people’s minds: music (a jazz band or rock band) and criminality (band of thieves). Sackler and McKinsey clearly fall into the latter class.

*[In the age of Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain, another American wit, the journalist Ambrose Bierce, produced a series of satirical definitions of commonly used terms, throwing light on their hidden meanings in real discourse. Bierce eventually collected and published them as a book, The Devil’s Dictionary, in 1911. We have shamelessly appropriated his title in the interest of continuing his wholesome pedagogical effort to enlighten generations of readers of the news. Read more of The Daily Devil’s Dictionary on Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.