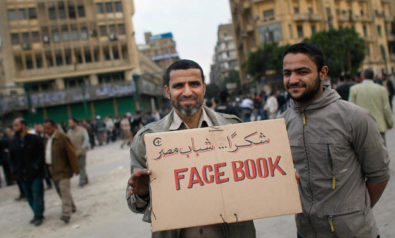

As Egypt marks the second anniversary of its revolution that ousted Hosni Mubarak, Egyptians are at the base of a new "purgatory", argues Sarah Eltantawi.

In Dante’s Purgatorio, the poets finally make their escape from hell just before Easter Sunday in the year 1300CE. Cato of Utica — purgatory’s gate keeper — at first regarded them as little more than unwanted refugees, therefore demanding to see evidence of their humility before they would be allowed to wash the grime of hell from their skin in the dew and rivers of purgatory. The poets acquiesced, soon finding themselves at a point near ground level on Purgatory’s slope, where they began to climb.

The allegory here foregrounds an analogy not between the poets and the revolutionaries, but between the revolution itself (the poets) and the weight of history (the gates of purgatory.) The relative ease of Hosni Mubarak’s ouster concealed how difficult it was always going to be to “revolve” that which is by definition stable and reinforced by inertia. Two years on, interpretive frames through which to assess the Egyptian revolution’s progress have become hardened. At least among “the political” whose numbers in Egypt have certainly increased, but are far out-swelled, as they always have been, by those who sigh wearily at the television while doing housework, or by those who ready themselves for work — or fill the days in other ways concealing a sinking heart because there is no work.

These ideological poles — at least since President Mohammed Morsi’s November 22 decrees — can be divided into two. Those who accuse the Muslim Brotherhood of massive overreach, fascistic tendencies, and hidden agendas — symbolized by the process of putting the constitution to a referendum, described as, “rammed through”. Along with those who feel the non-Islamist forces are unjustifiably refusing to accept the outcome of fair elections, and, by extension, have unfairly characterized the constitution drafting and ratifying process. What all parties can agree on is that Egypt is facing critically serious economic and attendant social problems that must be immediately addressed. The mood is somber.

There is no question that the honeymoon is over in Egypt. The question is: does Egypt need more romance, or does it need to make the best of the disappointing relationship it finds itself in? The most severe problem facing Egypt today is that there is little to no consensus on a vision of what the greater good actually looks like. Hence, the instinct is one of either creative destruction — mow everything over and start again (here the practicalities of such a radical undertaking are rarely elaborated) — or preserve and protect the stability that does exist in the country and build slowly; even if that means working with the devil himself.

At What Point are Fears About Islamism Justified?

Islamism carries a local and regional symbolism as, variously, the nightmare scenario that makes authoritarian regimes — in a triumph of the poverty of expectations — attractive for some as a necessary alternative (this is Bashar al-Assad and his supporters' main argument for continuing his bloody rule); or a symbol of culturally and historically “authentic” resistance figures. This particular mythology has been severely eroded of late, as Marc Lynch and others have argued. At the same time, the Brotherhood has been placed under unprecedented scrutiny and they have seemed, “unable or unwilling to reach out to mend shattered relationships.”

Then there are disturbing sentiments expressed by groups such as the Jama’a al-Islamiyya who are to the Brotherhood’s right, and have recently claimed in the Egypt Independent newspaper that they will hold a rally to “realize common interests among all the political forces”, and to emphasize “the necessity to apply shari'a as the principle concept of the stability of the people.”

On these peans to shari'a, I think Nathan Brown points out in his essay, “Debating the Islamic Shari'a in 21st Century Egypt,” that Olivier Roy and others are right when they argue that the debate about shari'a is more about symbolic authority than legal substance. Indeed, as Brown points out, the Brotherhood pivoted brusquely in response to political winds from the 1970s, when they called directly for the application of the shari'a, to their more contemporary calls for shari'a to be considered an “Islamic reference” (marja ‘iyya islamiyya).

Many of those outraged by Morsi’s decrees, and the Brotherhood’s general ham-fisted political approach, find their rage magnified by the frequently unspoken assumption that the Muslim Brotherhood is an unreliable political actor that is taking advantage of democracy to stack the nation’s institutions with their ideologues. It was this assumption that I have, until very recently, thought to be unfounded. I simply did not see evidence that the Brotherhood was wielding power to any more or disturbingly different degree than what I would imagine any other political actor would have been doing in their place.

Doria Shafiq

I thought that until I heard about what the new Islamist-dominated Ministry of Education has done to Egyptian feminist Doria Shafiq (1908-1975). They deleted her from the 2013-2014 school year edition of the National Education Textbooks for Grades 11 and 12, along with pictures of women killed during the 25 January revolution. The reason reported in the Egypt Independent by Mohamed Sherif, philosophy and national education adviser to the Ministry of Education, was that “some religious satellite channels” objected to her not wearing the hijab (headscarf).

Several lines have thus been crossed. For one, who is this “Mohamed Sherif” — a name so quotidian it nicely drives home the point that he is, in the end, “some guy” — to decide he can simply delete Doria Shafiq from the pages of history? Doria Shafiq, who stormed the Egyptian parliament in 1951 with hundreds of Egyptian women and emerged with the right for Egyptian women to vote and stand for parliament. Doria Shafiq, who was denied a university post in Egypt after earning her PhD at the Sorbonne in philosophy — an extraordinary achievement at the time for a man and certainly for a woman — for the explicit reason that she was a woman. Doria Shafiq, who was placed under house arrest by Gamal Abdul Nasser for 18 years until she flung herself from her balcony in 1975, taking her own life. Doria Shafiq, who was — by Nasser’s orders — erased from textbooks. Yes, this was already done once under an Egyptian government that started out revolutionary and ended up a dictatorship; that very dictatorial trend, epitomized by this disgraceful behavior and crude attitudes, is what sent Egypt into the slow ruin we are now obliged to deal with.

And so I must have a bit less patience with the Muslim Brotherhood. Because there is a pattern. Women are literally being erased; again.

This is where we are now, two years on. Those who were the most organized have won democratic elections. As we stand at the very base of our new purgatory — after a climb up from hell — humility and patience is still being demanded of us. There is a tension between the desire for a new romance to fight against the disappointments of our current relationship, and the pragmatic pull to make the current arrangement work as a matter of survival at a time when the country is almost bankrupt and attendant malaise sets in. In the midst of this, the Egyptian government flirts with dangerous and deeply offensive silliness with respect to Egypt’s heroines. The country certainly has no time for such stupidity.

This is not the revolution we asked for. And while it is important, I would argue, for the Egyptians with the loudest voices to be more cooperative with the government than I have generally found them to be, if the government, who do in fact have many important things to do, are going to waste our time, then they must be delegitimized and ousted through a legitimate political process. And the final, not particularly romantic legacy of the revolution two years on is simply that this is possible.

*[This article was first published in Die Tageszeitung in German.]

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment