The trajectory of Italy’s Northern League party is a case study of the complex ways in which perceptions of regional, national and ethnic identity operates in the contemporary politics of the radical right.

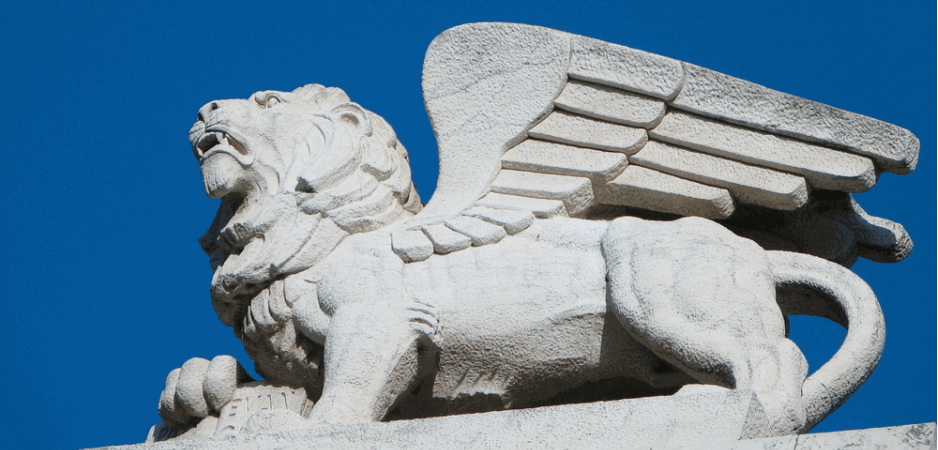

If you visited Venice in the spring of 2006 during the Italian elections, you could see billboards plastered with Lega Nord (Northern League) posters, depicting the figure of Alberto da Giussano, the mythical defender of Lombardy. Above Giussano was a large Lion of St. Mark, the symbolism demonstrating the absorption of Venetist ideology into the pan-northern rhetoric of Umberto Bossi’s Padania (his name for northern Italy). Bossi’s talent was to channel resentment of Rome and Brussels into a movement that made common cause between the regions of Northern Italy: Lombardy, Veneto and Piedmont.

Bossi’s movement was already feeding anti-migrant sentiment and fear of Islam in the 2000s. A 2006 television campaign for the Northern League saw Alberto da Giussano with a crusader flag galloping through a woodland scene. The accompanying text urged “respect for our land, our traditions, our history, honesty, courage, family, protection, liberty.” The video ended with the crusader raising his sword before he transforms into the Northern League symbol. In this fantastical image, “our land, our traditions” are identified with a Europe under threat from nameless, foreign outsiders. In a climate of suspicion of Islam and of immigration, the crusader image has, of course, a particular set of resonances.

Now the Northern League has transmuted into La Lega (the League), in a government coalition with the amorphous, populist Five Star Movement (M5S). Bossi has gone, forced to resign his leadership of the party after a financial scandal in 2012. In 2013, Matteo Salvini took over the reigns of the party. In June 2018, Salvini became Italy’s deputy prime minister and is, most observers concede, the most powerful politician in Italy. The League’s symbol still features the mythical Lombard knight with a fierce Lion of St. Mark embossed on his shield.

Changing Perceptions

But perceptions of the League have changed from a special interest party of northern separatists to a national anti-immigration and Eurosceptic movement similar to the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD). Salvini himself has adopted a persona that marries elements of more “traditional” conservative politics (the League’s current slogan, “The Common Sense Revolution,” was used by the British Conservative leader William Hague in 2001) with characteristics of the new alt-right.

Salvini’s tweets in short sentences punctuated with exclamation marks, similar to US President Donald Trump’s use of the medium. Salvini admires Trump, whom he met in April 2016, during the latter’s election campaign. Salvini tweeted admiringly about Trump’s respect for “legality and security.”

The trajectory of the Northern League is a case study of the complex ways in which perceptions of regional, national and ethnic identity operates in the contemporary politics of the radical right. From defending the desires of northern separatists to detach from Rome and southern Italy, the League’s current manifesto instead stresses “autonomy and responsibility” for all Italian regions which will result in fewer costs and more responsibility over spending. For Bossi, Padania was a “slave” to Rome. For the contemporary League, Italy is a “slave” to the European Union that has invited too many migrants.

In this story, regional autonomy is still important for the League, but can no longer be mapped onto a divide between North and South. Instead, Italians — whether Sicilians, Venetians, Lombards or Sardinians — stand in opposition to an oppressive and obsessively pro-migrant EU. Like UKIP’s Nigel Farage during the 2016 referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, the League plays on long-standing European fears of the Oriental “other”: “No [Never] to Turkey in Europe!” proclaims one League banner displayed on its website.

Salvini’s League successfully taps into deep, sub-rational anxieties about the vast continents to the south and east of Europe. His Twitter feed provides an almost gleeful litany of African asylum seekers in Italy supposedly arrested for heinous violent or sexual crimes. The League’s current slogan, “Italians First,” encapsulates the anti-migration rhetoric that has become so characteristic of the contemporary party.

Alongside this is an apparent concern for culture and patrimony, perceived as both regional and Italian. One of Salvini’s stunts saw him parading through the streets of Florence placing “for sale” signs on its monuments, including the copy of Michelangelo’s David in the Piazza della Signoria, emphasizing his rhetorical point about Italian culture being sold off by the European Union. Salvini also sees himself as a fierce advocate of Italian products like Parmesan cheese and Parma ham. On July 14, Salvini tweeted a photograph of himself in front of a vast Lion of St. Mark in Oppeano, Verona, to advertise the League’s annual festival.

International Alliance of Populists

Regional identity has not disappeared as a concern of this radical-right, Eurosceptic and anti-migration party. Rather, symbols of both regional and national culture have become part of a fluid set of tools to promote the nativist concerns of the League, concerns it seems to share with the movements in support of Trump in America and with various forms of radical-right nationalism in Europe. Salvini has made connections with the AfD, as well as Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France. One of the political figures to send early congratulations to the new Italian government was Nigel Farage, of UKIP. Like the League, UKIP combines a focus on local, regional concerns with rhetoric of a “British” national “history and heritage.” In particular, the national party has targeted small coastal towns, promising complete extraction from the European Union’s orbit.

A recent campaign, for example, promised to “Make Brixham Great Again.” Brixham is a fishing port in South Devon, where UKIP’s leaflets and slogans were targeted at local shoppers and café patrons, the party’s appeal based on its supposed ability to regenerate such towns by “liberating” them from the EU. Salvini’s recent call for “an international alliance of populists” against a “Europe of the elites” places the League in a transnational league of radical-right parties.

In this context, the League makes common cause with Steve Bannon’s ethno-nationalism in the United States and with the forces around Brexit in the UK. At the same time, Germany’s radical-right AfD have welcomed the coalition of the League and M5S, praising the two anti-establishment parties. Thus, whilst the League’s regional roots are still important, it now aligns itself with a loose group of forces opposed to the European Union, to “liberal” values, and to “elites” in general.

*[Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right is a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.