| ||

| ||

| ||

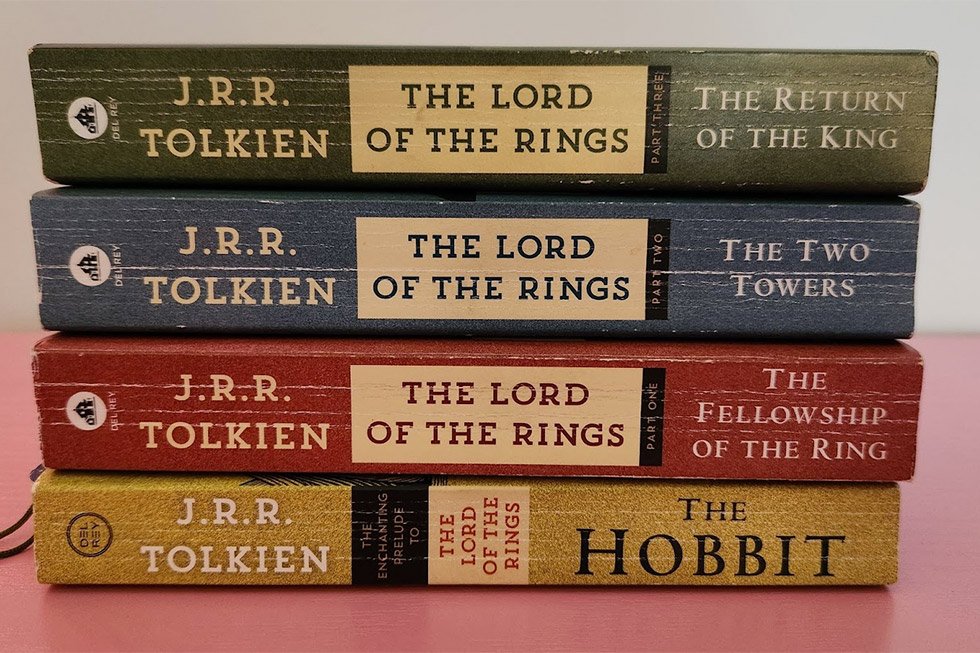

Dear FO° Reader, I am once again writing to you from Savannah, Georgia, in the good ol’ US of A. The weather here has been sporadic, with either incessant rain or intense heat. It’s not ideal for going out and joining society, but it’s perfect for staying indoors and watching my favorite movies. Luckily, those are my two favorite things to do. So, I spent several days at home introducing my roommate to the wonderful world of Middle-earth. We started with the theatrical editions, of course, as I didn’t want to scare her off by immediately jumping into a 12-hour movie marathon. Like most people who watch The Lord of the Rings, she was immediately hooked. Naturally, we had to watch the extended editions as well. After two movie marathons spanning a grand total of 21 hours, we finished what is arguably one of the most influential fantasy stories of all time. The author watches Aragorn’s coronation in The Return of the King. Author’s photo. Why The Lord of the Rings? J.R.R. Tolkien first came up with the idea of Middle-earth when he was still an Oxford undergraduate in 1914, at the outset of World War I. A war Tolkien went on to fight in as an officer in the British Army. After coming back from war, and with what appeared to be another world war on its way, Tolkien wrote The Hobbit, which the British publishing company George Allen & Unwin published in 1937. Seventeen years later, George Allen & Unwin published The Lord of the Rings novels as a continuation of not only The Hobbit, but also The Silmarillion (a published collection of Tolkien’s works that tells the history of Middle-earth). Author’s copies of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings In 2001, New Zealand director Peter Jackson released the first movie, The Fellowship of the Ring, followed by The Two Towers (2002) and The Return of the King (2003). The films — much like the books they adapt — have gone on to be a staple for many fantasy lovers, such as myself. Notably, The Return of the King has 11 Oscar wins, the most wins for a single film — a record it shares with James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) and William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959). Now, there are plenty of reasons why The Lord of the Rings is such a beloved story. The most apparent is that Tolkien gives a masterclass in worldbuilding, which put fantasy on the map as a mainstream genre. Pair this with the central theme of the preservation of love and hope in the face of evil, and you have one of the best pieces of fiction to grace the face of the planet. High praise, I know, but the story lives up to it. “But there is courage also, and honor to be found in Men” For me, arguably one of the best things about The Lord of the Rings is its depiction of masculinity. Not only do I believe it’s one of the best aspects of the story, but I also think it’s one of the most important, especially for our current era. We live in an age of “alpha males” and toxic masculinity, where you’ll hear someone tell little boys who cry that “there’s no crying in baseball.” From a young age, we teach boys that they need to keep their emotions to themselves when those emotions make others perceive them as “weak” or “soft.” Don’t cry, don’t healthily express your thoughts, just shove it all down until you explode. Because that’s the only real emotion men are allowed to express: anger. But fear, love, hope, pain or sadness? Forget about it. This is why there’s a male loneliness epidemic. It’s not because men can’t find women to fall in love with them; it’s because men have forgotten how to form deep platonic relationships with one another. They’re so terrified of being perceived as “gay,” “weak,” “feminine” or any other label people use to belittle men who show emotion that they decide not to show any at all. But Tolkien illustrates that men can be emotional and strong. Even more importantly, he showed us that it is through their emotions that men find strength. It would be easy to focus on the Hobbits in this discussion as they are known for valuing friendship, love and a quiet, simple life. But it isn’t through just the Hobbits that Tolkien gives us this portrayal of healthy masculinity; it’s everyone. Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits and Men alike. All of them outwardly express their emotions — they love, they laugh, they cry, they grieve — and they’re never weaker for it. Quite the opposite, actually, as it’s this emotional vulnerability, their capacity for love, that helps them succeed in saving Middle-earth.

Via Shutterstock. You would never call Aragorn, son of Arathorn, heir to the throne of Númenor and the rightful king of Gondor, weak. Yet he cries as he lays Boromir to rest. Nor would you say that of Boromir and Faramir of Gondor or Théoden and Éomer of Rohan. But Boromir sheds tears for his people, Faramir grieves his brother’s death, Théoden openly sobs at the grave of his son and Éomer wails while he cradles his injured sister in his arms. They feel fear, too. Does that stop them from being great warriors and kings of men? No. They are great because they are afraid. They look that fear in the face, and instead of cowering, they take action. They pick up their swords and fight. That’s what courage is. It’s not the absence of fear, but the ability to rise above it: “I see in your eyes the same fear that would take the heart of me! A day may come when the courage of men fails. When we forsake our friends and break all bonds of fellowship, but it is not this day. An hour of wolves and shattered shields, when the age of men comes crashing down! But it is not this day! This day we fight! By all that you hold dear on this good earth, I bid you stand, Men of the West!” They ride out to meet the death that greets them with open arms: “Arise, arise, Riders of Théoden! Spear shall be shaken, shield shall be splintered, a sword-day, a red day, ere the sun rises! Ride now, ride now, ride! Ride for ruin and the world’s ending! Death! Death! Death! Forth Eorlingas!” Tolkien shows that men can be afraid, and that being so doesn’t make them weak. Because the real weakness isn’t feeling the fear, it’s buckling in the face of it. “What about side-by-side with a friend?” Their biggest strength lies in the bonds that they form with one another. These men love each other deeply, and the most beautiful part of it all is that these bonds are strictly platonic. There is no fear of being judged for loving each other as they do. This is simply how the men in Middle-earth form friendships — the same way women do in the real world. Here is where I have to commend not just Tolkien for writing the story, but Jackson and the cast for bringing it to life. The love that these characters share is palpable. It’s in every action and word: Samwise Gamgee holding Frodo Baggins’s hand when Frodo is in the infirmary; Peregrin Took (Pippin) promising to take care of Meriadoc Brandybuck (Merry) while he cradles him in his arms; Aragorn laying a kiss on Boromir’s head; Gandalf the White wrapping his arms around a frightened Pippin to comfort him. Theirs is a Fellowship “eternally bound by friendship and love,” and they aren’t afraid to show it. As I stated earlier, it is this love that allows them to succeed on their quest to save Middle-earth. If Frodo had not had Sam to remind him that “there is some good left in this world,” he would have succumbed to the dark power of the One Ring long before he reached the steps of Mount Doom, where he must go to destroy it. If the members of the Fellowship had not held true to each other, the Dark Lord Sauron’s forces would have swept over Middle-earth, to “the ruin of all.” There is so much to learn about what it is to be a man from this story. Being a man means loving your friends, expressing yourself and being afraid. It’s holding onto hope and fighting for it. It’s loving so profoundly that you carry your best friend up a volcano because you might not be able to carry his burdens, but you can carry him. It is this portrayal of masculinity that makes me firmly believe that all men/boys should watch these movies at least once (and read the books if they feel so inclined). The world would be a better place if men took a page out of Tolkien’s book and remembered what masculinity really means. Stop teaching your sons that tears are a sign of weakness. Stop shaming them for being vulnerable. Learn to love one another without fear of a label. Be open and brutally honest with your feelings — love, cry, scream, rage, laugh. You’ll find that embracing vulnerability is the only way to be strong. Now, this is where I must bid you adieu. Farewell, my dear readers, and always remember: “I will not say: do not weep; for not all tears are an evil.” Kaitlyn Diana Associate Editor | ||

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news

must

be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and

editors cost money.

So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

| ||

| ||

| About Publish with FO° FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact |

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment