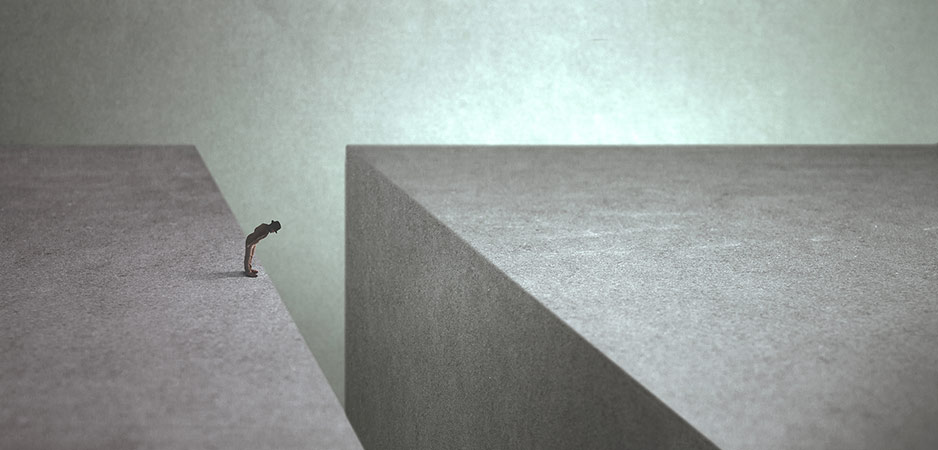

It seems that on the highest levels, everything is going wrong. In the past few years, populism and authoritarianism have reared their ugly heads. The economy has just reached historic lows, and we are only beginning to reap the effects of a ruined environment. Suicide rates are climbing, refugee crises continue like low-grade political fevers, and now we’re facing a global pandemic. It’s as if we’ve reached the edge of the civilizational map and are staring over the edge, discovering that, indeed, here there be monsters.

But that’s not the end of the story. Hannah Arendt, the celebrated German-American philosopher noteworthy for her love of the world, strove to make sense of horrors such as totalitarianism and the Holocaust. Many of her answers may be useful to us today. In fact, her work suggests that there could be a golden — not just a silver — lining to coronavirus-motivated social distancing, and it lies in the ancient connection between politics and psychology.

Dialogue With the Self

Perhaps surprisingly, Arendt ends her masterwork, “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” published in 1951, with a reflection on loneliness. She points out that since ancient times, tyrants have worked to isolate citizens from each other. Sowing separation and distrust among citizens prevents people from acting in concert and generating power that can overthrow tyrannical dominance. What was different, even at Arendt’s time of writing, was the epidemic of loneliness.

For Arendt, isolation was strictly a political experience, the inability of citizens to act together in the public space, generating power. Loneliness was a more existential experience, characterized by the inability to connect with others or being exposed to others’ hostility. Today, loneliness has reached epidemic proportions, especially among young adults.

Paradoxically, Arendt’s antidote to both isolation and loneliness was not togetherness, but solitude. Solitude is different from both isolation and loneliness in that it requires being physically alone, but, in solitude, the self is not existentially alone. The self keeps company with itself, in dialogue with itself. While both loneliness and isolation are marked by disconnection and desertion, in solitude the individual remains connected to herself and the world. In the dialogue of self with self, the solitary individual represents the world to herself. Conversely, the two conversing selves of solitude converge through reconnection with another human being who affirms the solitary individual’s unique, unexchangeable identity.

For Arendt, the practice of solitude issues in thought, conscience and creativity. In “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” she notes that “all thinking, strictly speaking, is done in solitude and is a dialogue between me and myself.” Indeed, solitude is the natural condition of the philosopher. In “The Human Condition,” Arendt comments further that “to be in solitude means to be with themselves, and thinking, therefore, though it may be the most solitary of all activities, is never altogether without a partner and without company.” Moreover, for Arendt, the activity of thinking generates insights that may be committed to paper and shared with others, crossing from thought into creation, gaining permanence and becoming part of our shared world.

The dialogue of the self with the self in solitude is also the source of conscience. In her introduction to “The Life of the Mind,” Arendt returned to the trial Adolf Eichmann, a central figure of the Third Reich’s Final Solution. Specifically, she reexamined her notion of the banality of evil, noting that with Eichmann, extreme evil didn’t seem to come from pride, envy, hatred, covetousness or moral monstrosity, but rather from sheer thoughtlessness. She writes:

“I was struck by a manifest shallowness in the doer that made it impossible to trace the incontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer — at least the very effective one now on trial — was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous. There was no sign in him of firm ideological convictions or of specific evil motives, and the only notable characteristic one could detect in his past behavior as well as in his behavior during the trial and throughout the pre-trial police examination was something entirely negative: it was not stupidity but thoughtlessness.”

Arendt noticed Eichmann’s utter helplessness during his trial, his inability to know what to do or say in the absence of procedure or routine. She goes on to say that “clichés, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality, that is, against the claim on our thinking attention that all events and facts make by virtue of their existence.”

Even at the time of writing, Arendt commented how “this absence of thinking … is so ordinary an experience in our everyday life, where we hardly have the time, let alone the inclination, to stop and think.” Arendt raises the question of whether thinking itself was opposed to evil-doing, regardless of the content of thought, and linked the activity of thinking with conscience: “the very word ‘con-science’ … means ‘to know with and by myself,’ a kind of knowledge that is actualized in every thinking process.”

From Tyranny to Totalitarianism

Finally, solitude is necessary for creativity. Creativity, poeisis, necessitates separation from action, praxis, and the world of common concerns. However, the isolated, creative individual remains connected to the shared world of things, and in creating something tangible adds to our shared world. In “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” Arendt mentions private creativity as a mode of coping with tyranny: When the public space is destroyed under tyranny, the individual may at least retreat into the private space with her own thoughts, or with creativity. Indeed, historically, the arts have often flourished under enlightened dictators of various stripes.

All three effects of solitude — conscience, thought and creativity — are essential for world-renewal. In fact, they created the life-world we inhabit in the first place. For Arendt, “world” is a technical term — it is the durable space we are born into and inhabit, and hopefully leave behind when we die. It’s comprised of laws, literature, art, music, philosophy, institutions and all the physical things that both bring us together and separate us, sheltering and orienting us in our shared life. It is human-made, but more durable than human life. At the same time, because it’s human-made, it does get worn down and stands in constant need of renewal. This is part of the task for each generation.

This should be comforting news when we read that in America, trust in other people and key institutions is failing, particularly among younger adults. Arendt would remind us that this is to some extent normal — institutions erode over time. The situation has become dire only because we haven’t properly engaged in renewing the world, in part because we haven’t properly engaged in solitude. We’ve forgotten how to be alone.

Remember those monsters? Authoritarian politics, frightening ideologies and senselessly destructive behavior have resurfaced with a vengeance. Arendt would argue that there’s a connection between the epidemic of isolation and loneliness, and the increasing draw of populist and authoritarian movements. In “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” she argues that loneliness itself is pre-totalitarian. It’s a sense of desertion by all, including oneself, that leaves the individual vulnerable. She writes:

“What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience of the evergrowing masses of our century. The merciless process into which totalitarianism drives and organizes the masses looks like a suicidal escape from this reality. The ‘ice-cold reasoning’ and ‘the mighty tentacle of dialectics’ which ‘seizes you as in a vise’ appears like a last support in a world where nobody is reliable and nothing can be relied upon.”

When “nobody is reliable and nothing can be relied upon,” the antidote is solitude, the dialogue of the self with the self, which generates conscience, thought and creativity. These, in turn, rebuild the world.

One caveat: For Arendt, solitude is possible under tyranny, but not under totalitarian domination. Tyranny controls the public space, but leaves the private space alone, preserving the capacities of thought, conscience and creativity. Totalitarianism invades the private space, disrupting the self’s presence to the self through terror, loneliness and ideology. The challenge today in practicing solitude is not to allow oneself to become mentally colonized, to instead preserve connection with oneself and with the world.

A Call for Heroes

In this story, we all can be the hero. Many are on the frontlines of the pandemic as their jobs require their physical presence to keep our world running. But those encouraged to practice social distancing should try to also practice solitude, not succumbing to terror, rescuing the dialogue of the self with the self.

Our world is sorely in need of renewal, but renewal most likely won’t come from the top. It will come from below, in the everyday choices made by individuals. Ultimately, what solitude restores is the capacity for beginning, the ability to bring something new into the world. For Arendt, this capacity to bring something unique into a world needing renewal is a gift each of us receives at birth. For her, it constitutes a sort of miracle and is a source of faith and hope.

Our task today is to transform moments of loneliness into solitude. While anyone who finds oneself alone can practice solitude, social distancing provides the perfect opportunity to regain this lost art. Solitude is more necessary than ever, both for weathering the coronavirus and for restoring the world. After spending time in solitude — engaging in thought, examining our conscience, creating something new — we can reengage with the “trusting and trustworthy company of [our] equals” to renew the world.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.