A dangerous cycle for immigrants has begun. On April 20, President Donald Trump announced that he would sign an executive order to temporarily halt immigration into the United States in order to curb the spread of COVID-19. As of April 1, 90% of the world’s population already resided in a country that implemented at least partial border closures. With the intention of stopping the spread of COVID-19, these border closures come at a moment when hostility toward immigrants and opposition to immigration is widespread. Not surprisingly, other political leaders have also used this crisis as an opportunity to halt asylum seeking and deport refugees, including in Canada and many European countries.

The pre-virus political climate was already characterized by skepticism of international migration, and to the extent that political leaders mobilize fears of immigrants, restrictive immigration policies could endure long after the pandemic. These fears will not make immigration less critical to national economies, however, and the tension between nativist fears and the demand for migration will remain. Thus, a more likely scenario is that most countries will lift restrictions on immigration in the coming months.

Opening Borders

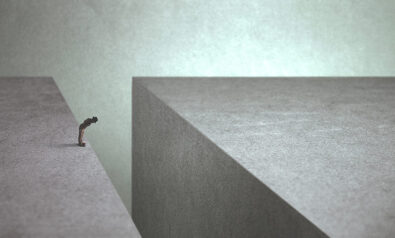

When the borders open, there will be a spike in international migration. Increased border control generates a build-up of unmet demand for opportunities to migrate from sending countries, where remittances will decline and unemployment will increase. Demographic research suggests that when disasters and wars have restricted behaviors such as fertility, marriage and migration, these temporary suppressions have resulted in subsequent “spikes” of such behavior.

Based on recent migration trends, an estimated 7.5 million foreign nationals would have traveled to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries and Russia for work or long-term stays in 2020. With a suppression for three to six months of an estimated 1.7 to 3.5 million migration trips, the subsequent spike in migration will not go unnoticed — especially not by radical-right parties poised to exploit COVID-19 to mobilize for more restrictive immigration policies.

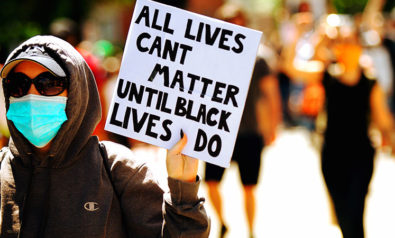

Hate in the Time of Coronavirus

How is this mobilization facilitated? Sociological theories suggest that influxes in immigration can be associated with prejudice due to perceived threats, or, on the other hand, they may induce positive intergroup contact and ultimately reduce prejudice. While people may over time become familiar with high levels of diversity so that small increases in the relative share of an outgroup no longer intensifies prejudice — as has been the case with anti-Muslim attitudes in the Netherlands — migration spikes have the potential to upend that trend.

For example, influxes of immigration have been tied to radical-right violence against and hostility toward migrants, asylum seekers and foreigners in Germany in the 1990s and in 2014-15, as well as in Norway, Russia, Britain and the United States at various points in time. As nativist fears of immigration increase, so too does the ability for the radical right to lobby for exclusionary policies consistent with their neo-nationalist ideology.

The vicious cycle of suppression, spikes in migration, renewed hostilities and reintroduction of restrictive policies could continue for years after the pandemic. This is particularly true in light of evidence that restrictive immigration policies almost never result in their intended goal of stopping migration. Paradoxically, such policies instead tend to change migration from legal and temporary to undocumented and long term.

Radical-Right Mobilization

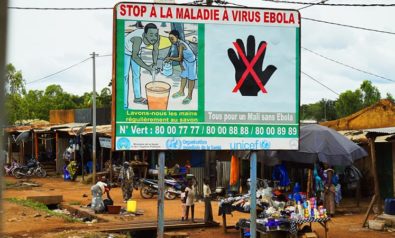

There is another particularity of the COVID-19 restrictions that makes radical-right mobilization particularly likely. The fact that it was a pandemic that precipitated the border closures in most countries means that migrants have already been stigmatized as carriers of disease. Of course, the initial spread of COVID-19 was facilitated by movement, in the form of both tourism and migration, and, to be clear, border closures are helping curb the spread of the disease.

Nevertheless, political rhetoric on the dangers of tourism has not yet emerged, while violent scapegoating against people labeled as non-native has: against Asian Americans in the United States, against African migrants in parts of China, against those perceived to be of Chinese or Asian descent in Europe, and surely other cases that have yet to be reported. In most democracies, laws exist to protect migrants from discrimination or persecution, but enforcement of any such legislation is contingent on the will of political leaders to do so in the face of anti-immigrant prejudice, radical-right mobilization and increasing neo-nationalist claims.

The world is in dire need of responsible political leadership to navigate this crisis. This is not the first call for leadership in the wake of a viral epidemic. Through the 1980s and into the late 1990s, hostility toward and violence against people suspected of having HIV were widely reported in the United States. Gay men in particular were discriminated against in housing and labor markets, perpetuated in part by the failures of then-President Ronald Reagan’s early response to the growing public health crisis, which his administration treated as a joke.

The parallels with today’s political rhetoric on COVID-19 are not difficult to find. In the 1980s, in the context of homophobic attitudes and marginalization of gay men and women, Reagan insisted that AIDS was nothing more than a “gay plague.” Today, in the context of neo-nationalist sentiment and marginalization of immigrants, Trump insists on calling the novel coronavirus the “Wuhan virus,” to the point of alienating allies and disrupting G7 cooperation. Finding a parallel strategy to break the vicious cycle that now threatens immigrants is more difficult.

Gay rights organizations, initially formed during Stonewall, reorganized and mobilized around the HIV/AIDS crisis, and eventually federal funds were allocated to HIV prevention and research. Today, US-based immigration activist groups have demanded protections for immigrants in the coronavirus relief package, and migrant workers from Romania have begun to mobilize in Austria.

We have yet to see the ways governments will respond to the vicious cycle of suppression, spikes and stigmatization. We do not yet know the extent to which COVID-19 will have dangerous implications for immigrants and far-reaching consequences for the future of international migration. Yet a plethora of social science suggests that, without interventions, COVID-19 will dramatically impact immigrants and the migration systems on which the global economy and national labor markets rely.

*[The Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right is a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

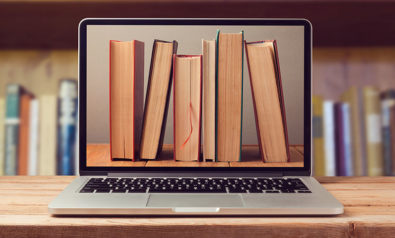

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.