On April 6, it was reported that the Commission on Human Rights was calling for stronger measures to tackle the increased rates of domestic violence incidents in the Philippines due to the lockdown measures that were implemented on March 16. The quarantine is worsening the problem of domestic abuse suffered mostly by women and children and, of course, those in the LGBTQ community who are especially vulnerable to such violence. Within the context of lockdown and quarantine, victims of domestic abuse and violence are also experiencing equally increased difficulties in seeking help.

As Gaea Katreena Cabico points out in her piece for the Philstar, according to the Center for Women’s Resources, at least one woman or child is abused every 10 minutes in the Philippines. Similar to other parts of the globe, this is an alarming issue that the state is being called to address in addition to managing the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis.

How to Fight Domestic Violence During a Global Pandemic

On March 16, the entire Luzon region, which includes metropolitan Manila, a city of nearly 13 million, was put under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) ordered by President Rodrigo Duterte. Different cities and municipalities within the region began implementing curfews, drastically reducing the movement of Filipinos in and around public spaces. Several checkpoints between the metropolis and its neighboring provinces were established. Shopping malls, gyms, bars and other nonessential businesses began shutting their doors to the public.

These measures allow Filipinos to leave their homes only to purchase food, medicine and personal protective equipment from essential businesses such as supermarkets and pharmacies. As in other parts of the globe, ECQ is part of the country’s strategy to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis. At the start of the quarantine, there were 140 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the Philippines. As of May 20, the number has climbed to 13,221 confirmed cases with 842 deaths and 2,932 recoveries.

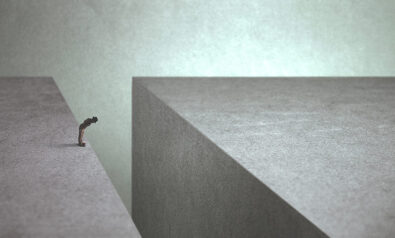

Lockdown Inequality

The side effects of the quarantine measures almost immediately magnified the already glaring class differences and economic inequalities in the country. With newly implemented restrictions of movement and checkpoints, as well as the suspension of public transport, news coverage of the first few days of the quarantine highlighted the strife of workers, most of them medical and front-line staff, attempting to enter Metro Manila from the provinces to attend work. These include employees without access to private vehicles and who until the commencement of the quarantine relied on public transportation such as the pubic rail system, jeepneys and busses. Parts of Luzon have only begun to gradually lift some of the restrictions on movement for employees of selected industries under the modified enhanced community quarantine, or MECQ.

The country’s poorest cannot afford to work from home or practice social distancing due to crowded, impoverished or precarious living conditions. Moreover, much of Luzon’s residents have lost their means of income while being asked to remain in their homes. The authorities are faced with the complex task of providing for families who are in need of food, basic goods, medicine and financial aid in a timely fashion.

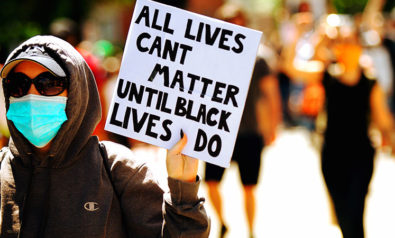

Several articles have already explored how the crisis surrounding COVID-19 has amplified existing social, political and economic inequalities at both state and global levels. As Max Fisher and Emma Bubola note in The New York Times, the economically disadvantaged are likelier to die from the disease. Also, “even for those who remain healthy, they are likelier to suffer loss of income or health care as a result of quarantines and other measures, potentially on a sweeping scale.” The rural and urban poor, the elderly, migrant workers and persons with disabilities were certainly already in vulnerable social and economic positions prior to the spread of the pandemic and to the debilitating quarantine restrictions. But lockdown protocols or any kind of quarantine measures also intensify cases of domestic abuse and gendered violence worldwide — whether physical, emotional, psychological or a combination of all three. This has already been noted in a number of recent reports in regard to the global spread of the coronavirus.

Lara Owen provides insight into domestic abuse cases in China during lockdown, including urgent social media appeals calling attention to these incidents, writing for the BBC that “some women have created posters reminding people to counteract domestic violence when they see it and not be passive bystanders. The hashtag #AntiDomesticViolenceDuringEpidemic #疫期反家暴# has been discussed more than 3,000 times on the Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo.” According to The Guardian, “from Brazil to Germany, Italy to China, activists and survivors say they are already seeing an alarming rise in abuse.”

The physical barriers that lockdown presents for victims make it harder for them to seek and obtain help. Professional care or assistance, including medical help and therapy, are more difficult to obtain simply because public and private health-care systems, as well as government services and personnel, are prioritizing those affected by the disease.

These are extremely trying times for victims of abuse, putting states in a difficult dilemma. On the one hand, families and individuals need to remain locked down within the domestic sphere in order to prevent the spread of infection. Yet these very measures and protocols only further endanger women and families who already find themselves in violent situations as they are being asked to remain confined within the same (often cramped) spaces as their abusers.

Gendered Freedoms and Restrictions

In the Philippines, the complex issues brought up by COVID-19 continue to pose great challenges for the victims of domestic abuse, but the social, cultural and economic backdrop already had barriers in place that impeded certain gendered freedoms. According to the Gender Gap Report 2020, the Philippines remains the top country in Asia in terms of narrowing the gap between men and women in categories such as educational attainment, health survival and economic participation and opportunity.

However, at the same time, mostly due to its Roman Catholic culture and political ties to the Catholic Church, the Philippines didn’t have comprehensive legislation that supported reproductive health and family planning until the passing of the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012, which was only implemented in 2017 after being initially blocked by the supreme court. Moreover, it is the only country in the world apart from the Vatican that does not legally recognize or offer the option of divorce. Many advocates who continue to fight for divorce and reproductive rights do so on behalf of the women who seek state and church-sponsored separations from unhappy marriages, as well as the right to make their own decisions on the number of children they want to have.

As the contours of the domestic space are reconfigured by this pandemic, it is important to remember that these abuses are not necessarily new products of the recent limitations in mobility. For those in abusive environments, lockdown protocols exacerbate these situations due to physical restrictions in their movements. But the social, religious, political and cultural infrastructure in the Philippines had already been designed in such a way that many gendered freedoms were already being restricted by the state long before the pandemic.

The measures that are now set in place to “flatten the curve” of COVID-19 unfortunately exacerbate the very dynamics that allow gendered violence to continue. Lockdown protocols can therefore be seen as additional hindrances to vulnerable women and children who already deal with a compilation of restrictions of certain freedoms surrounding their bodies, identities, relationships and intimate practices.

COVID-19 continues to claim lives, exhaust our health-care resources, sidetrack our economic progress and limit our physical and social movement. But it also operates as a lens that provides a magnified glimpse into injustices and restrictions that were already embedded in our societies.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.