Sarah Eltantawi suggests that the debate on Scottish independence can provide useful insights for the Arab world.

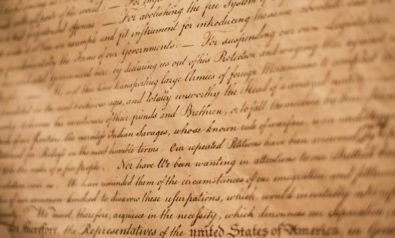

Those with attention turned habitually elsewhere in the world may not know the details of the Acts of Union of 1707, unifying Scotland and England. These acts, passed under the tutelage of Queen Anne, created the United Kingdom. The acts are two: one, passed in 1706 called the Union with Scotland Act which was authorized by the English Parliament, and its compliment passed by the Scottish Parliament in 1707, called the Union with England Act.

Three hundred and seven years after the Acts of Union were passed, on September, 18, 2014, the question of Scottish independence will be put to referendum, and the Scottish people will have their say about their future. Now, well over a year before the vote, the UK and Scottish governments have begun producing arguments, documents and speeches making their respective cases for or against Scottish independence.

Having recently spent a few weeks in Scotland, I must confess that after many discussions with both Scots and English people living there, several aspects of the debate have left me curious and intrigued.

Our Mistakes

First, independence qua independence would seem without deeper analysis to be a kind of instinctual good. Any proud and ambitious peoples would naturally hew toward sovereignty — that all important and famously over-determined concept of nationalism. It is obviously less romantic to parse the question further to ask questions about economic implications, the question of nuclear weapons: Will an independent Scotland be a nuclear-free zone? Or questions about wider relationships with Europe — all of which prompt more reserved thinkers to either oppose independence or advocate for a more circumscribed form of it that maintains essential interdependencies with England.

But among some of the everyday, working class Scots I had the opportunity to engage in conversation with about the referendum, independence was an obvious goal and a point of pride.

One source of frustration I heard was that many foreigners (I think this was a polite way of saying, mainly, “Americans”) think of Scots, as a new friend I met in the Galloway area of Scotland put it, as “that cherubic man wearing a skirt on yer biscuit packet,” and are ignorant entirely of the realities of underprivileged life in what are called “schemes.” Known in the US as “projects,” these are government subsidized housing units that are crowded and often quite dangerous. The most notoriously violent schemes in Scotland are in and around the city of Glasgow, ranked by the Institute for Economic and Peace (IEP), a project of the UK Peace Index in April of this year, as the UK’s “most violent area” (though violence in Glasgow has actually decreased in recent years).

This image of the formless, cartoonized Scot, set against an image of a pacific land of rolling hills, cow pastures and stunning landscapes greened by endless sheets of rain, is frustrating for many Scots living in dangerous conditions under the threat of violence. My friend who grew up in the schemes outside Glasgow thinks the unemployment rate is “easily 50%,” creating undifferentiated masses of young men hanging around the housing units accumulating aggressions, with no proper outlet to release them. For him and his girlfriend, who expressed similar sentiments of frustration, they feel not only ignored and misunderstood, but taken advantage of by England economically. Independence is a fundamental step toward recognition as a contiguous economic and political unit, a state they see as an essential first step to improving their lot: “At least if there are mistakes, they are our mistakes.”

Then there are the English people in Scotland, who are of different breeds. The first are the English who have purchased second homes in Scotland, often holiday homes that are not owner occupied, frustrating the locals. Others have opened businesses and migrated for economic reasons. I believe it is safe to say that loosely speaking, this category of the English would tend to oppose independence along with more well-healed Scots. Some English people living in Scotland can be found atop the gorgeous hills, leading peaceful and eccentric lives among the vast pastures and frequently forbidding weather. This group — drawn to Scotland in part to be free — wholeheartedly support independence.

Cooler Heads and Propaganda Wars

From what I can make out of the word from the “chattering classes” in Scotland, however — to be found mainly in Edinburgh and St. Andrews — the consensus seems to be turning against independence. This opinion is framed in plaintive, reasonable cadences, aimed at transmitting a sense that cooler heads should and will prevail. The arguments center around the belief that the potential arrangement has not been thought through and that there are so many loose ends — such as what currency would an independent Scotland use, what would be the border situation with England, what of nuclear weapons, and more — that this discussion is a distraction that will be more destructive than constructive.

Meanwhile, the official propaganda war on both sides has begun.

Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond published a report last week laying the economic case for independence. Called “Scotland’s Economy: The Case for Independence,” and launched at a manufacturing plant in Falkirk, the report argues that Scotland has a wealth of resources that can only be properly harness in the context of independence.

Salmond, leader of the Scottish National Party, which is notably far less noxious than similarly-named and themed political parties in Europe, goes on to argue that the all-important oil resources in the North Sea could be immensely profitable for an independent Scotland if an oil fund was set up as in Norway, one of Europe’s most prosperous nations today. Moreover, argues Salmond, Scots have contributed more taxes per citizen over the past 30 years than the average citizen of Britain. George Osborne, the UK chancellor, warned in response that Westminster may not permit an independent Scotland to use the Sterling.

Salmond responded rather extraordinarily, it seemed to me, declaring, according to the BBC that: “More than 50 countries have voted to become independent from London since the Second World War and they’ve never expressed any wanting to go back.”

The Crumbling Empire?

As an Egyptian-American who has spent quite a bit of time studying colonialism — in particular British colonialism and its machinations, strategies and effects — I find myself disoriented and fascinated by this debate. From my perspective, the loss of Scotland is a stunning and almost unimaginable — perhaps final — blow to the British Empire that we have watched splinter in the past sixty or so years, often leaving difficult, if not disastrous, legacies in regions such as the Middle East. I like to think that I am not given to conspiratorial thinking, but in this sense, I find it very hard to believe indeed that London is going to shrug their shoulders and let Scotland vote itself off the Isle, as it were, taking a massive amount of the “Queen’s territory” with it. But what is even more surprising to me is the reaction of some of the (left-leaning) English people I have put my deep skepticism to. One of them calmly replied, to summarize the sentiment: “Well yes, but you see, both Scotland and England are democracies.” And this, to their minds, puts an end to the doubt.

I must admit that though I am skeptical that the spirit of democracy can trump the realpolitik of what is, at this point, admittedly, the symbolism of empire in the form of Scotland arranging itself firmly under the crown, I am impressed with this sentiment and surely wish it every success. This confidence in democracy must be what it is like to operate from a position of strength and of self-determination — where decisions about what form one’s territory will take are measured and concluded based on one’s national interest, not imposed by outsiders or the most ruthless inside players. I know that is an idealistic accounting of the debate over the future of Scotland, but it is true enough to have me despairing once again about the processes of territorial determination currently unfolding in the Arab world, where regional cooperation does not have a deep, credible and indigenous modern history. This is one of many catastrophes, and it is due in large part to legacies of colonialism and ongoing, related wars. But the region needs to move beyond this terrible history eventually, and perhaps observing the quiet yet weighty debate on the British Isles will provide not only some curiosities, but also some insights.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment