It’s probable that white Americans didn’t understand the full extent of the roughness of law enforcement in predominantly black neighborhoods until 1991 when they saw the video of Los Angeles police officers beating the African American Rodney King. Since then Americans of all ethnicities have witnessed repetitions to the point where they have almost become inured to the sight of black people being brutalized and sometimes killed by white officers.

Reverberating questions

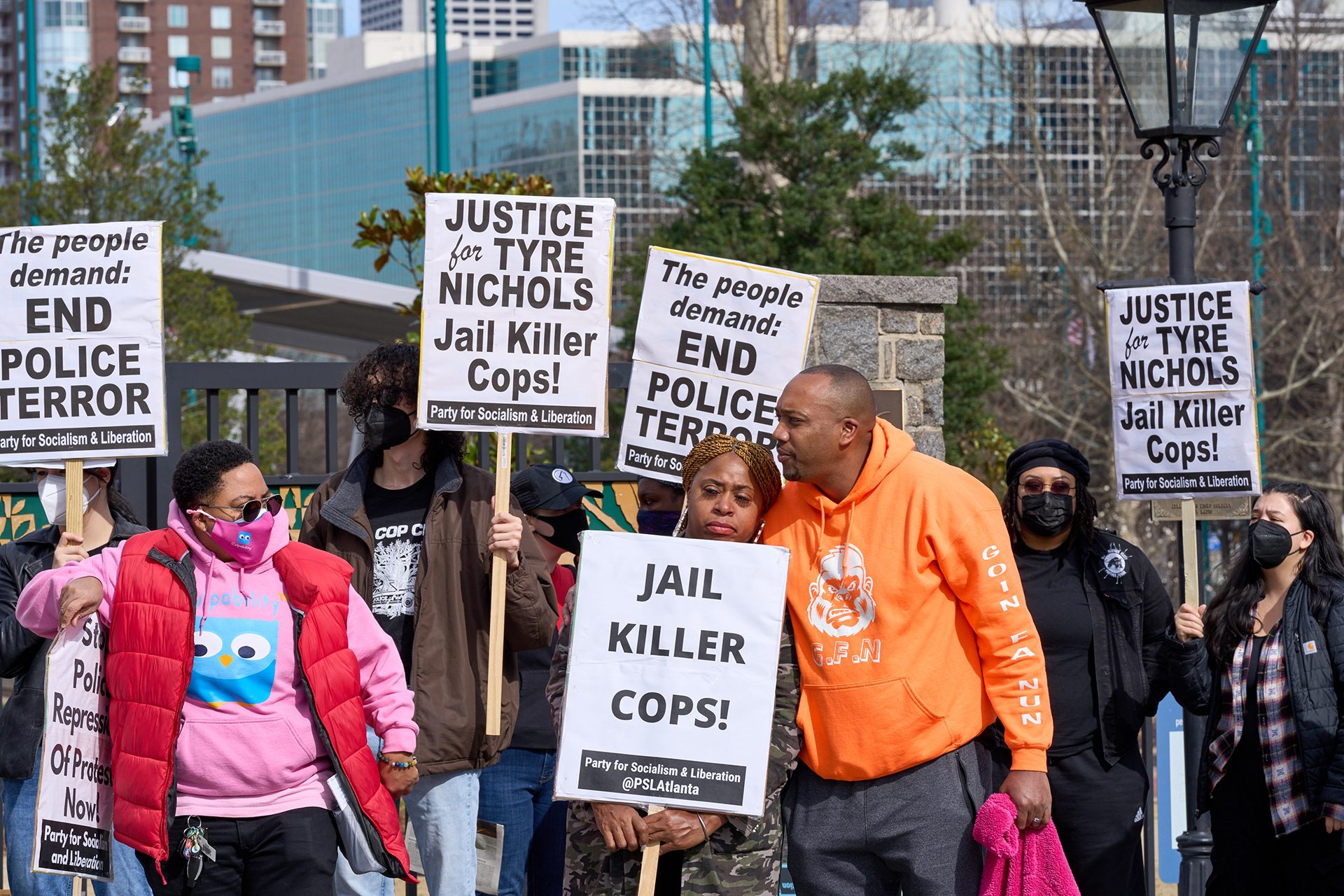

The term institutional racism is, as a matter of course, invoked to explain the persistent pattern of behavior. No amount of hand-wringing, policy directives or even new presidents seems to make much difference. But the killing of Tyre Nichols will make a difference. It is a killing that will leave a searching and complicated legacy — and I mean legacy, not just influence, because it will shape the way we make sense of institutional racism and perhaps wonder if this is a meaningful explanation after all.

The five officers involved in the beating — Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr. and Justin Smith — were indicted on various criminal charges, including second-degree murder. They are all African Americans. How can this be institutional racism, or any other kind of racism? The reverberating questions have no ready answers.

Some might insist liberal hypocrisies have disguised subterranean racism for decades and whites remain in charge of everything, including the way we all think. A form of co-optation, appointing and promoting blacks to positions of relative privilege, has served to distract everyone from who rules. Cerelyn Davis, a black woman, is the chief of police in Memphis, Tennessee, where the killing took place.

Undernourished Aspirations

Little in this world is as potent a consensus: Everyone agrees that institutional racism is a force in today’s society. So, what exactly is it? The term itself was introduced in 1967 by black activists Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. Racism is “pervasive” and “permeates society on both the individual and institutional level, covertly and overtly,” they wrote.

Later writers, like Douglas G. Glasgow, sought to restrict the use of the concept to express the fact that, in the 1960s and 1970s, “The ‘for colored’ and ‘whites only’ signs of the thirties and forties had been removed, but the institutions of the country [United States] were more completely saturated with covert expressions of racism than ever” (in The Black Underclass). Glasgow wrote further: “Institutional racism (which involves ghetto residents, inner-city educational institutions, police arrests, limited success models, undernourished aspirations, and limited opportunity) does not only produce lowered investment and increased self-protective maneuvers, it destroys motivation and, in fact, produces occupationally obsolete young men ready for underclass encapsulation.”

On these accounts, institutional racism is camouflaged to the point where its specific causes are virtually undetectable, but its effects are evident in the procedures of industries, political parties, schools and police forces. Defining it as inclusively as this made institutional racism a resonant term and one which has gained currency of late. But its generic status invites criticism about its lack of specificity and its limits as an explanation of such a wide range of social processes.

A Collective Failure

In the UK in 1999, a well-intentioned report into the murder of black London teenager Stephen Lawrence used the concept as a kind of secret weapon. “A collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their color, culture, or ethnic origin. It [institutional racism] can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes, and behavior which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.”

The Macpherson report, as it was known, concluded that London’s Metropolitan Police was guilty of carelessness though not deliberate (“unwitting”) racism. “It persists because of the failure of the organization openly and adequately to recognise and address its existence and causes by policy, example and leadership.”

Countless British organizations put their hands up and acknowledged they propagated institutional racism. After all, if it was unintentional, or inadvertent, no individual or single department was to blame and everyone went scot-free. Even “enlightened” organizations, such as religious and educational institutions could own up to racism with relative impunity. This, it could be argued, was the fatal flaw: Every time, someone claimed institutional racism, it was nobody’s fault. Or, if individuals were to be blamed, it’s because they behaved consensually in a way that doesn’t upset the “system.”

By capturing the manner in which whole societies, or sections of society, were and still are affected by racism, or perhaps racist legacies, long after racist individuals have disappeared, we approach racism’s emergent property — it comes into being through the interactions of people and stays long after those people have disappeared. The racism that remains may be mostly unrecognized and unintentional, but, if never disclosed, it continues uninterrupted.

Imperishable?

Critics insist that institutions are, when all is said and done, the product of conscious human endeavors and, no matter how deeply entrenched, it’s an error to suppose that institutional racism is a cause of behavior. Humans, not institutions, attack other humans.

This makes the Nichols case especially troubling: If we acknowledge the formidable, persistent power of racism to affect practically every feature of modern western society, then we’re forced to reckon with our apparent helplessness to subvert it: Every effort over the past 60 years since civil rights appears to have crumbled.

On the other hand, if we remind ourselves that humans ultimately wield the batons, what do we make of blacks mercilessly assaulting other blacks? Are we still going to call it racism? Because, if we are, it changes the word’s meaning and somehow diminishes its impact. Whites no longer have sole culpability and maybe they never did. In fact, an acknowledgement of the presence of institutional racism does no harm and may even burnish self-righteous liberal credibility.

Conceptual criticism apart, institutional racism has demonstrated a practical value in highlighting the need for continuous, relentless action in expunging racist discrimination rather than assuming it will just fade away. Its mention in the same discourse as the Nichols death should also unsettle us because it reminds us of the almost imperishable capacity of racism to distort modern life in ways we never imagined.[Ellis Cashmore’s latest book is The Destruction and Creation of Michael Jackson.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.