The often-told narrative of the Middle East focuses on the rise and fall of empires like the Achaemenids, Abbasids and Ottomans. Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 330 BCE is another well-known chapter. Yet, a significant power that emerged in the wake of Alexander’s death — the Seleucid Empire — remains largely obscure.

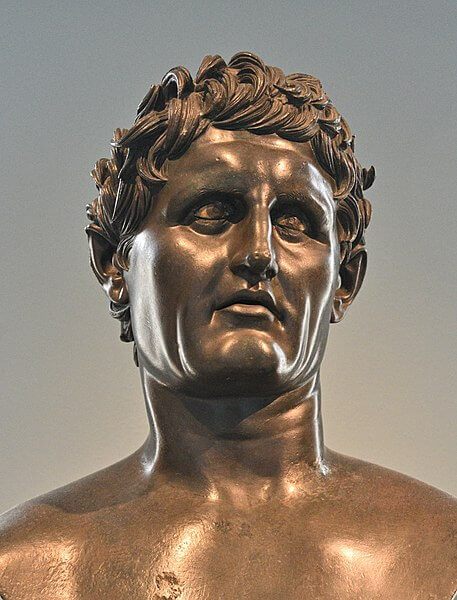

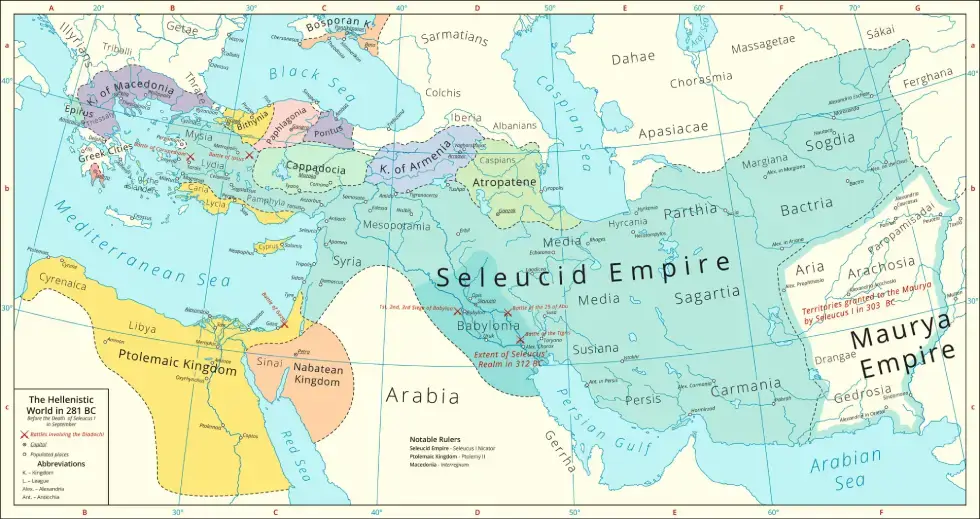

Founded by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander’s Macedonian generals, the Seleucid dynasty carved out a vast kingdom. They and Alexander’s other successors, collectively known as the Diadochi, vied for territory within the empire after Alexander’s chosen regent, Perdiccas, failed to hold onto power. When the dust settled, the Seleucids found themselves in control of the lion’s share of the empire. At its peak, the Seleucid Empire stretched from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) to the Indus Valley in India.

Despite its geographical dominance and lasting influence, the Seleucids are often relegated to a footnote in discussions about the Middle East. They are overshadowed by their Egyptian counterparts, the Ptolemies, who are famous in the West for collecting the Library of Alexandria and for the exploits of their last member, Cleopatra. The Seleucids enter Western narratives primarily in the context of their eventual defeat by the Romans.

This neglect has resulted in a significant gap in our understanding of the region’s development. The Seleucid Empire played a crucial role in shaping the Middle East, both culturally and politically.

Architects of the Hellenistic world

The Seleucids’ impact extended far beyond the battlefield. They played a crucial role in bridging the gap between Europe and India, fostering cultural exchange and inadvertently shaping the world through their interactions with other powerful empires.

The Seleucids were heirs to the vast Hellenistic cultural tradition. This influence manifested in their grand architectural projects, characterised by a blend of Greek, Mesopotamian and Egyptian styles. Cities like Antioch, their capital, boasted impressive public spaces, colonnaded streets, and temples adorned with statues in the Greek tradition.

Seleucid architects also played a key role in the development of urban planning, with a focus on geometric layouts and civic amenities. In philosophy, the Seleucids embraced the intellectual currents of the Hellenistic world. Epicureanism, Stoicism and Scepticism all flourished under their patronage, attracting scholars and fostering lively debates.

One of the most significant contributions came from Megasthenes, a Seleucid ambassador stationed at Pataliputra, the magnificent capital city of Indian monarch Chandragupta Maurya, in the 3rd century BCE. Credited as one of the first Europeans to write extensively about India, Megasthenes’s work, the Indica, became a cornerstone for understanding the subcontinent.

His accounts, despite potential biases inherent in any ambassador’s view, remain a valuable source of information. Megasthenes’s detailed observations on Indian society, including the complex caste system, the role of elephants in warfare, and the practice of sati (widow self-immolation), as well as politics and geography, provided a window for Europeans into a previously unknown world.

Megasthenes’s work wasn’t just a standalone account. It served as a foundation for later writers like Strabo, who used and interpreted the Indica. It shaped European perceptions of India for centuries to come. Strabo cited Megasthenes’ descriptions of outlandish creatures, likely misinterpretations of real animals or cultural practices, which fueled European fantasies about the exotic East.

The Seleucids may not be a household name, but their enduring legacy is undeniable. They were facilitators of cultural exchange, purveyors of knowledge and patrons of art, architecture and philosophy. Their influence transcended geographical boundaries and temporal limitations, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient world.

The Jewish rebellion against the Seleucids

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Seleucids, however, comes from their interaction with a small but ancient people in the southwestern corner of their empire: the Jews.

The Seleucids cast a long shadow over Judea in the 2nd century BCE. Under the oppressive reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who earned the punning epithet “Epimanes” (the Mad) for his increasingly erratic and oppressive religious policies.

Antiochus deeply offended his Jewish subjects. He desecrated the Second Temple in Jerusalem, erected a statue of Zeus, and mandated the worship of Greek gods. He sought to hellenize Judea by promoting the Greek language, customs and religious practices. This included the suppression of traditional Jewish practices such as circumcision and Sabbath observance, a direct assault on Jewish identity and faith.

This oppression ignited a rebellion. In the small village of Modin, a Jewish priest named Mattathias Maccabaeus and his sons refused to comply with Antiochus’ decrees. Their defiance sparked a wider uprising. Skilled fighters with unwavering faith, the Maccabees adopted guerilla tactics against the Seleucid army. Their deep familiarity with the Judean terrain and religious fervour proved advantageous, leading to early victories. Judas Maccabeus, Mattathias’ most prominent son, emerged as a charismatic leader, uniting diverse Jewish factions against a common enemy. His leadership and military prowess were instrumental in the early successes of the rebellion.

The Maccabean Revolt transcended the battlefield; it was a struggle for the very essence of Judaism. This period had a profound impact on Jewish thought and identity. The trauma of the Seleucid persecution prompted the creation of apocalyptic texts such as the Book of Daniel and the Book of Enoch. These works expressed themes of divine judgement, righteous suffering, and eventual deliverance, reflecting the anxieties of the Jewish people.

The Maccabean spirit of resistance against tyranny and unwavering faith in the face of oppression continues to resonate with Jews today. Their story serves as a potent reminder of the lengths to which communities will go to defend their beliefs.

Two books, now known as 1 and 2 Maccabees, became a part of the Christian canon of the Bible and told the tale of the Maccabean revolt to subsequent generations. Likewise, the Jewish tradition of Hannukah continues to commemorate the successful resistance of the Maccabees against their Hellenistic overlords.

The repercussions of the Maccabean Revolt extended far beyond Judea’s borders. The weakened Seleucid Empire presented an opportunity for the Romans, who exploited the conflict to expand their own regional influence. By using Judea as a pawn in their power struggle, the Romans undermined the Seleucids. By the 1st century BCE, the Romans had made themselves masters of Anatolia, Syria and Palestine.

While Judea dominates the narrative of the Seleucids’ struggles in the West, the empire’s eastern borders also faced challenges. In their Iranian territories, revolts aimed at reviving Persian customs posed a significant threat. Ultimately, the Seleucids failed to maintain control of Iran, paving the way for the rise of the indigenous Parthian and Sasanian dynasties.

This set the stage for a division of the Middle East between the rival Roman and Iranian empires, a pattern which would not be altered until the Arab Muslim conquest of the Levant and Iran seven centuries later.

[Ali Omar Forozish edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment