On February 21, one of the authors of this piece explained the backstory of the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict. Armenia was once a part of the Ottoman Empire, while Azerbaijan belonged to the Qajar dynasty of Iran. As both empires weakened and fell, Armenia and Azerbaijan ended up in the Soviet Union.

In 1991, the Soviet Union fell as well. Since then, Armenia and Azerbaijan have been at odds with each other over Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan. Until two months ago, Armenians lived in Nagorno-Karabakh, an area within Azerbaijan. Azeris still live in Nakhichevan, an area within Armenia that borders Iran and Turkey. Yes, this sounds complicated but so are most imperial hangovers.

On September 19, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh. This autonomous ethnic Armenian enclave called itself the Republic of Artsakh. Within 24 hours, this so-called republic ceased to exist. Now, Azerbaijani military forces control Nagorno-Karabakh. The Artsakh Defense Army stands disbanded and people who lived here for centuries, if not millennia, have fled to Armenia.

David J. Scheffer of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) states that Armenians are “experiencing ethnic cleansing at warp speed.” Others defend Azerbaijan and argue that its troops are only restoring sovereignty to territory that is rightfully theirs. Armenia had controlled Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding areas, all legally Azerbaijani territory, until a few years ago.

Azerbaijanis claim that this Armenian exodus is voluntary. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev promised to protect Armenian civil rights in Nagorno-Karabakh, but fleeing Armenians feared persecution and massacre “after years of mutual distrust and open hatred between Azerbaijan and Armenia.”

A complicated history that goes back centuries

Over time, various empires have conquered and controlled the South Caucasus. Generals like Cyrus, Alexander and Pompey swept through this mountainous region. In antiquity, winning in the South Caucasus was essential if you wanted to be called “the Great.”

Why is the South Caucasus so important for the likes of Cyrus or Alexander the Great? Geography provides us the answer.

The South Caucasus lies at the crossroads of empires. To its west, lies the Mediterranean Sea which was the locus of the Macedonian, Roman and Ottoman empires. To its north and east (beyond the Caspian Sea), lie the great Eurasian grasslands that were once dominated by the Mongols and now by the Russians. To the south of the South Caucasus lie the Tigris and Euphrates rivers — historically known as Mesopotamia — and the Iranian plateau that was the power base of the Persian Empire.

This mountainous region has been the meeting place for great empires and the battleground for great powers. Romans and Persians traded Armenia back and forth. Over the past five centuries, Safavid Persia, Ottoman Turkey and the Russian Empire have controlled different parts of this territory at different times. Their successor states still jostle over the South Caucasus today.

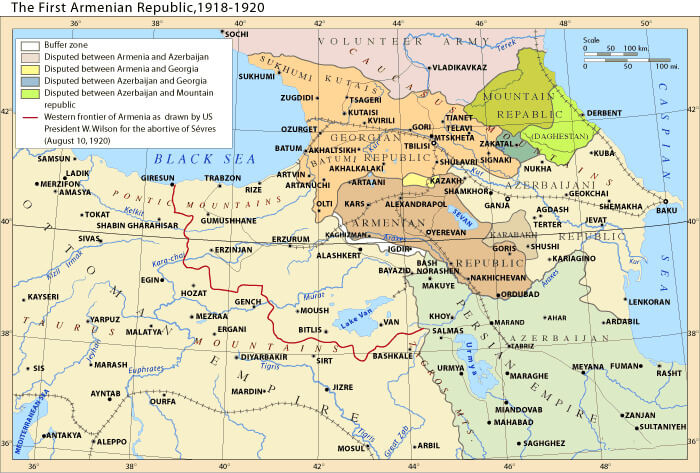

World War I was critical in forging modern South Caucasus. Tsarist Russia faced disastrous defeat. In 1917, a revolution erupted and Russian control of this region evaporated. Idealists forged the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, which disintegrated into Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia within five weeks. In this age of ethnic nationalism, a multiethnic state proved a bridge too far, especially for the fractious South Caucasus.

Like the Russians, the Ottomans fared poorly in World War I. Armenia took advantage of Ottoman weakness to take control over Nakhchivan. Rebellions by the local Muslim population followed but Armenia managed to retain control. In the case of Zangezur and Karabakh, Azerbaijan stood in Armenia’s way and both these young countries fought inconclusively.

When World War I ended, the Ottoman Empire collapsed as well. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk set out to create a modern Turkish nation state. Out went a multiethnic empire, in came a more ethnically homogeneous nation. The Turks expelled the Greeks and the Armenians from this new state. Modern Turkey was built through ethnic cleansing, although the Ottomans had set the ball rolling with the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

Atatürk was rebelling against the peace settlement imposed by the victorious allies in 1920. The Treaty of Sèvres wrested the Arab and Greek portions of the Ottoman empire from Turkish control. The British and the French divvied up the Arab lands between themselves. Along with Italy, they also carved Turkey into spheres of influence. Atatürk defeated the occupying forces, scrapped the old treaty and negotiated the far more favorable 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

The now largely forgotten Treaty of Sèvres provided for an independent Armenia. The idealistic Woodrow Wilson proposed that the US be the protector of this new Armenia. The 1920 treaty envisioned an Armenia four and a half times larger than the one today. Sadly for Wilson and Armenia, the US turned isolationist at the end of the war. The US Senate withdrew from the League of Nations and torpedoed Wilson’s plans for Armenia.

While the US turned inward, the newly formed Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), now better known as the Soviet Union, went back to its expansionist imperial Russian roots. As one of the authors explained in his earlier piece, the Soviet 11th Army took over the South Caucasus, including Armenia and Azerbaijan, in 1920 itself. The Treaty of Sèvres was stillborn.

For the next seven decades, Armenia and Azerbaijan were Soviet republics. Moscow drew their borders largely on ethnic lines. The USSR granted Zangezur to Armenia, Nakhchivan became an Azerbaijani exclave and Karabakh became an autonomous province within Azerbaijan. The Soviets dubbed Karabakh the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) because Nagorny Karabakh in Russian simply means the highlands of Karabakh.

The dormant Nagorno-Karabakh volcano explodes

By the late 1980s, the Soviet empire began disintegrating. The Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989. On December 31, 1991, the Soviet Union itself dissolved. Ethnic tensions held in check by communist repression erupted like a dormant volcano.

In 1988, ethnic Armenians living in the NKAO demanded their region be transferred from Soviet Azerbaijan to Soviet Armenia. Conflict exploded into all-out war when the Soviet Union collapsed. Fighting only ceased in 1994 and Armenia emerged as the winner. Armenian troops took control over Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent districts. Armenia now controlled 20% of Azerbaijan. An estimated one million Azerbaijanis became refugees and internally displaced persons. Armenia did not have it all its own way though. About 300,000–500,000 Armenians from Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan made their way to Armenia.

The end to war in 1994 did not lead to peace. Deadly incidents continued. Both sides used troops, special operations forces, artillery, other heavy weaponry and, more recently, drones. In April 2016, fighting broke out but stopped after just four days. Yet hundreds died on both sides. On the whole, an uneasy peace persisted until 2020.

During this uneasy peace, Armenia forged a security partnership with Russia while Azerbaijan developed a close relationship with Turkey. A shared Muslim faith and a common Turkic ethnic identity helped. Even though Armenia and Russia are part of the Oriental Orthodox Christian traditions, Moscow still sold weapons to Azerbaijan and played both sides.

Starting 2007, things changed dramatically. BP discovered gas at “a Caspian-record depth of more than 7,300 meters” about 70 kilometers southeast of Baku. Flush with gas wealth, the balance of power began to shift in Azerbaijan’s favor in the 2010s. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey rejected Atatürk’s secular European identity and embraced a neo-Ottoman foreign policy. Erdoğan’s political Islam led to greater military support for Azerbaijan and Baku’s geostrategic position improved. More gas money and Turkish military support gave Azerbaijan the edge over Armenia in the latest edition of South Caucasus geopolitical chess.

In late 2020, Azerbaijan made its decisive move and succeeded in reclaiming much of the territory Armenia had occupied since 1994. The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War lasted 44 days and left at least 6,500 dead. Azerbaijan was unable to break through the defenses of Artsakh and Russia brokered an uneasy truce. Nearly 2,000 Russian peacekeepers were to enforce the peace. These troops were deployed along the three-mile-wide Lachin corridor, the sole overland route connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

The ceasefire agreement granted Azerbaijan control of Nagorno-Karabakh’s cultural capital, Shusha, which Armenians refer to as Shushi, and several other towns. Azerbaijan also gained surrounding Azeri territories that Armenians had held since 1994. Local Armenians got to retain control of the northern half of the region, along with Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh. Future peace talks were to decide the final political status of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Azerbaijan grabs a historic opportunity with both hands

Needless to say, the peace did not hold. In December 2022, Azerbaijan closed off the Lachin corridor. The Russia-Ukraine War had broken out on February 24, 2022. The 2018 Velvet Revolution had ousted the Russia-friendly Republican Party that had been in power since 1999. After the revolution, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan took charge. Armenia began to extricate itself from the arms of Russia and started flirting with the US. This poked the Russian bear and earned Pashinyan’s Putin’s ire.

Azerbaijan had a once-in-many-generations opportunity and Baku seized it with glee. In December 2022, Azerbaijan violated the 2020 ceasefire agreement and closed off the Lachin corridor. This ten-month blockade denied 120,000 Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh food, fuel and medicine. Putin’s peacekeepers stood idly by and Artsakh’s fate hung in the balance.

By April, Armenians found themselves in a dire situation. Pashinyan dramatically relinquished Armenia’s claim to Nagorno-Karabakh in an effort to stop the long-running conflict. This failed to bring peace. On April 23, set up a checkpoint on the Lachin corridor, which was called “the road of life” for Artsakh. Neither Russian peacekeepers nor Western powers did much to help. By September, it was all over. Azerbaijan controlled all of Nagorno-Karabakh, Artsakh evaporated and Armenians fled to Armenia.

A little more than two weeks before Azerbaijan’s decisive move, Pashinyan had declared that “solely relying on Russia to guarantee its security was a strategic mistake.” History may judge his ill-judged statement as a historic blunder. Pashinyan turned to the West in general and the US in particular to guarantee Armenia’s safety. However, to paraphrase a Chinese proverb, the mountains were high and the emperor was faraway. The US had far too many pots on the boil to worry about Armenia.

Pashinyan forgot one simple fact: realpolitik is a rough game. The EU needs Azerbaijani gas after putting sanctions on Russia. In 2021, Europe imported 8 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas from Azerbaijan. This year, gas imports are expected to be 12 bcm and are on track to double by next year. Clearly, gas supplies trump the unity of Christendom for the EU. Post-Brexit UK is in the money because of BP. So, Armenia can expect little help from a land that was once the realm of Richard the Lionheart.

Azerbaijan has also been able to win over Israel to its side. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 13% of Israel’s arms exports were destined for Azerbaijan in the 2017-2021 period. They comprised more than 60% of Azerbaijani arms imports and included drones, missiles, and mortars. Furthermore, the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) reveals that 65% of Israel’s 2021 crude oil imports came from Azerbaijan.

Much more discreet than SIPRI and OEC figures are the close strategic collaboration between Israel and Azerbaijan for realpolitik reasons. Intelligence Online claims that Israeli military and intelligence contributed to Azerbaijan’s victory in Nagorno-Karabakh. Naturally, Israel has an ax to grind. Azeris comprise 16% of Iran’s population, three times the population of Azerbaijan. Although they have yet to rebel against Tehran, Azeris report widespread discrimination despite being largely Shias. By backing Azerbaijan, Israel is winning over Azeris and could foment trouble in the future against Iran. More importantly, Israel’s elite organizations — Unit 8200, Mossad and Sayeret Matkal — reportedly use Azerbaijan as a base of operations against Iran. For Israel, Armenia is eminently expendable in the pursuit of its national security goals.

For the US, Azerbaijan is of vital national interest because it borders both Russia and Iran, two key enemies. Washington cannot displease Baku too much and push it into the arms of Russia. Despite a powerful Armenian American diaspora that has historically backed the Democrats, the Biden administration turned the Nelson’s eye to Azerbaijan’s actions and did not back Armenia.

In contrast, Turkey is backing Azerbaijan to the hilt. Less than a week after Azerbaijan’s victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, Aliyev hosted Erdoğan in Nakhchivan. The two hailed this victory and signed a deal for a gas pipeline. Erdoğan was “very pleased” to “connect Nakhchivan with the Turkish world.” Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan paralyzes NATO, which cannot support Armenia. Most Muslim countries in the nearby Arab world to the more distant Pakistan, support Azerbaijan.

Poor Pashinyan is isolated. He has found himself with two not-very-useful friends: neighboring Iran and faraway India. Both are not powerful enough to stave off disaster for landlocked Armenia. Besides, the Israel-Hamas war raging has cast Armenia further into the shadows. No one is likely to act against further Azerbaijani aggression.

What happens next?

Erdoğan and Aliyev have clearly signaled that Nakhchivan is next on the menu. They fear that Armenia could do this 460,000 strong Azeri enclave what Azerbaijan did to the Armenian enclave in Nagorno-Karabakh. Ethnic cleansing is a game two can play and Azerbaijan must press home its advantage before the tide turns.

Therefore, Baku seeks the Zangezur corridor, a transport link through Armenia’s southernmost province Syunik to Nakhchivan. This landlocked Azerbaijani territory has a small border with Turkey and a much larger one with Iran. The former backs the Zangezur corridor while the latter opposes it. The descendants of the Ottomans and Safavids are clashing again in the South Caucasus.

Under Erdoğan, Turkey aims to breathe fire into the Organization of Turkic States, an attempt to bring together Turkic peoples all the way till Kazakhstan. Once Turkish horsemen dominated Central Asia. Today, Erdoğan is looking east and south, not west and north, to expand Turkey’s influence. Therefore, the Zangezur corridor is an opportunity to create a new trade route between Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and China.

Despite academics like Anna Ohanyan calling the Zangezur corridor a violation of Armenian sovereignty and a challenge to the global rules-based order, Yerevan and Baku are engaged in peace talks. On December 7, they agreed to exchange prisoners of war. After failed mediation by the EU, the US and Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan are engaged in direct bilateral discussions. Yet mutual distrust is high and both sides are unlikely to come up with a lasting peace deal.

So far, Armenia has played a weak hand badly. Pashinyan has lost much of the goodwill he gained during the Velvet Revolution. Even before Azerbaijan’s conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh, Pashinyan’s popularity was declining precipitously. Now, many Armenians revile him as a weak and ineffective leader who has led the country to disastrous defeat.

Pashinyan has continued to offend Moscow by refusing to allow Russian troops to conduct military exercises and declining to attend an alliance summit. Armenia has also joined the Treaty of Rome that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC has issued an arrest warrant for Putin. By joining such an organization, Pashinyan is spitting in the tsar’s face and inviting further Russian wrath.

Notably, Armenia is economically dependent on Russia. The country’s landlocked geography does not make things easy. Turkey lies west, Azerbaijan east, Georgia north and Iran south. Therefore, about 40% of Armenian exports make their way to Russia. Armenia depends on Russian grain, oil, gas and basic goods almost completely. Gazprom owns all of Armenia’s gas distribution infrastructure. The country depends on remittances from Armenians working in Russia. In 2022, $3.6 billion out of the total remittances of $5.1 billion came from Russia.

Armenia still remains a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization, Commonwealth of Independent States and Eurasian Economic Union. Since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine War, the Armenian economy has become even more dependent on its Russian counterpart. Currently, Pashinyan is visiting Russia, promising greater economic bloc cooperation but Putin is unlikely to give his rebellious satrap much of a break. Russia is grinding down Armenia into submission and will only relent when Pashinyan is no longer prime minister.

With little external support or internal legitimacy, Pashinyan is in no position to make peace. With Turkey’s help, Azerbaijan will put Armenia under duress and drive a hard bargain. If Pashinyan does not capitulate, Azerbaijani troops can drive home their advantage. This time, the conflict might draw Turkey and Iran into the fight. Russia will wait and watch but eventually intervene. Israel, NATO, the UK and the US might also find themselves sucked into this conflict. Yet again, the South Caucasus has become a powder keg but few are paying this region the attention it deserves.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment