Fair Observer Founder, CEO & Editor-in-Chief Atul Singh speaks with cultural anthropologist and historian Steven Huyler about his multi-decade connection with India. Huyler reflects on arriving in India in 1971, the hospitality he received and the ways his experiences transformed his life and work. Together, they explore Western misconceptions, India’s diversity, the contrasts between North and South and the enduring complexities of caste and identity.

India–Pakistan 1971 war

Huyler recalls arriving in India on his 20th birthday, October 27, 1971 — just before the Indo-Pakistani War. He had traveled overland by local transport through nine to 11 countries, including Pakistan, before crossing the tense border into India. He describes soldiers, camouflage, armaments and propaganda signs — “Crush India” on one side, “Crush Pakistan” on the other. This stark moment was his first objective impression of India, framed by war.

India’s hospitality

On entering India, Huyler bicycled a rickshaw himself out of empathy for its elderly driver. His first night was at the Golden Temple in Punjab, where he felt dazzled by the atmosphere and devotion of the community. Soon afterward, in Delhi, he met Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Mahatma Gandhi’s associate, a freedom fighter and founder of India’s cottage industries program. Through her, he gained introductions to more than 60 families across India, each instructed to “take care of this boy.”

This opened the doors to Indian homes where he observed daily life and family dynamics. He was particularly moved by the intimacy between grandparents and grandchildren, and by the centrality of the pooja room (a room dedicated to religious rituals and prayer), which he came to see as the cornerstone of family life. Families treated him as an uncle, a gesture of intimacy that warmed his heart and helped him learn to quiet his own presence as a tall American outsider.

Transformed by India

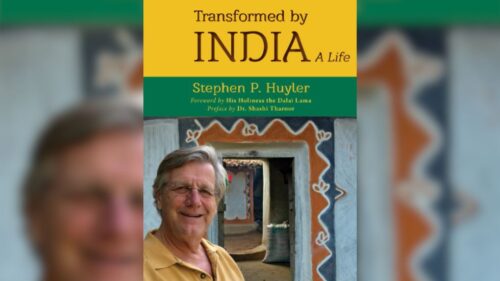

These early encounters became the foundation for his book, Transformed by India: A Life. Huyler describes the work as chronological storytelling, infused with humor, beauty and joy, but also “stark horrors.” He insists that it would be wrong to leave out the difficult aspects of India, because they too shaped his transformation.

Over decades, Huyler has written seven books, curated 25 major museum exhibitions and led tours of India. He sees himself as a “bridge of understanding between the West and India,” or what he calls a “cross-cultural surveyor.” This gives him both breadth — an overview few others share — and limitations, as he remains an outsider without the deep immersion of a specialist.

What the West gets wrong about India

Huyler believes such a bridge is essential because of persistent Western ignorance. For the first 30–35 years of his work, he rarely found India mentioned in history or art history books, except superficially. In his experience, many in the United States reduce India to stereotypes of gurus, Sanskrit and Hinduism. While he acknowledges that Brahmanical Hinduism is part of the picture, he emphasizes that India’s broader culture is built by hardworking people whose contributions are often overlooked.

To ignore India, home to one in five human beings, is in his words a “disservice” to history. He argues that Western civilization has long been interwoven with Indian culture, whether or not it has been recognized. He aims to amplify those overlooked voices.

Why India is different

For Huyler, India’s staggering diversity is its defining quality. He considers it “far more diverse than Europe,” pointing to differences in music, literature, physical traits, food and language. Tamil literature and Carnatic music, he notes, are entirely different from their North Indian counterparts. He highlights how most foreigners think of Punjabi cuisine as “Indian food,” a misconception akin to equating English cooking with French or Italian.

Despite the differences, India has always nurtured interrelationships across its cultures. This constant exchange and adaptation is, in his view, what makes India so unique and endlessly fascinating.

India’s North–South identity

Huyler describes sharp contrasts between North and South India. South India, he says, has historically been less patriarchal, more literate — especially in women’s education — and more protective of women’s creative traditions. The North, by contrast, has endured a more violent history of invasions, partition and trauma, which has left deeper divisions.

At the same time, similarities remain. Across both regions, women are seen as the nucleus of the home, and their creative expression is valued, even if in different forms. Today, Huyler observes cultural cross-pollination everywhere: Southern cuisine like dosas and momos are moving north and northern foods like roti are appearing on southern thalis (meal platters).

Caste and identity

Huyler emphasizes that India’s identity is not disappearing but constantly redefining itself. He acknowledges that urbanization and English education among elites have shifted traditions, but insists that the masses continue to sustain their cultures. He admires how even in Mumbai’s slums, people retain identity and resilience, contrasting this with Western communities where victimhood and a sense of loss often dominate.

He regards caste as deeply complex. It has horrific aspects but also provides continuity and cultural grounding across all Indian religions. Singh points out the injustices of hereditary positions, such as unqualified priests in the city of Varanasi. Both speakers note communities — like Marwaris (an ethno-linguistic group in India’s Marwar region) in business and Tamil Brahmins (an ethnoreligious community in the state of Tamil Nadu) in intellectual life — that have benefited from caste traditions. Huyler admits there is no clear solution to balancing justice with cultural continuity.

Huyler closes with self-reflection: striving to step off his American “high horse,” decode his Western privilege and minimize the distortion of his outsider’s lens. His latest book, Transformed by India: A Life, is available now.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment