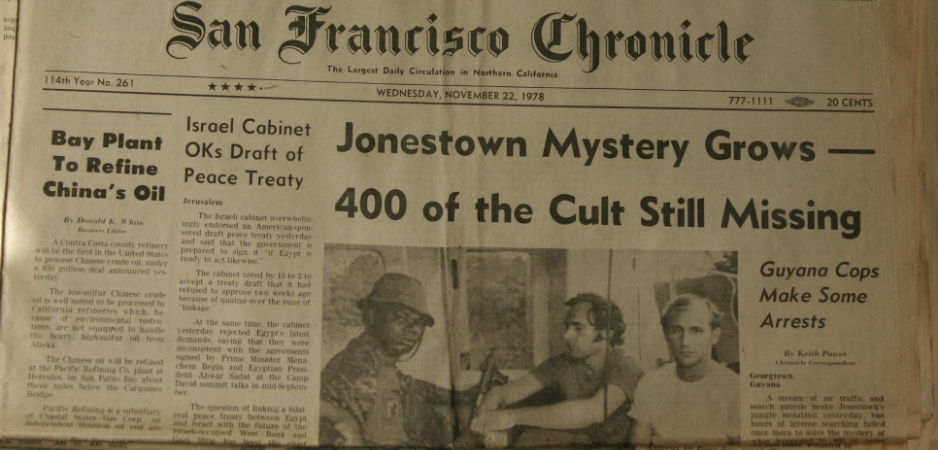

On November 18, 1978, Jim Jones, a charismatic leader, ordered the followers of his People’s Temple to kill themselves, in what would become known as the Jonestown Massacre.

The 1970s was the decade when civil rights came of age, in all its imperfections. Legislation in 1964 and 1965 was intended to guarantee the rights of all citizens to political and social freedom and to end discrimination. Ten years later, the keys to paradise were nowhere to be seen. African-Americans were, in material terms, no better off. Riots along the length and breadth of America, and the rise of dissident groups like the Black Panthers were reminders that the US was still a nation divided racially.

So when Jim Jones, an evangelist from Indiana, promised a new heaven on earth, a self-sufficient egalitarian community that was independent of white America, his proclamation reached receptive ears. There were was no shortage of communes, cooperatives and other kinds of settlements at the time, many inspired by visions similar to Jones’. But his vision had clarity. There was an almost Nietzschean logic to his message: The master morality of America would maintain whites’ domination over blacks, who were destined to remain subservient no matter what legal or cultural change lay ahead. His alternative was to relocate physically to Guyana, a country on the northeast coast of South America. Here he intended to create his new heaven on earth.

On November 18, 1978, Jones ordered his followers to drink a cyanide-laced drink, resulting in the loss of 909 lives. In addition a politician, three journalists and a defector were shot on Jones’ orders. Having watched the dystopian implosion of his hopes, Jones turned a gun to his head and killed himself, bringing a nightmarish conclusion to one of the most perplexing and harrowing episodes in history.

Barely Comprehensible

It was barely comprehensible: over 900 suicides. There were no precedents to aid understanding, only unreliably chronicled events either side of the common era suggesting that comparable events had happened in antiquity. In 1802, about 400 followers of Leo Delgrès, who led a resistance movement against slavery in Guadeloupe, are thought to have ignited gunpowder stores rather than surrender to French militia. In 1945, some 700-1,000 residents of Demmin, in Germany, killed themselves after pillaging by the Soviet Red Army. Civilians hanged themselves, slit their wrists, shot themselves and their family members, and ingested poison. Jones’ followers were not under threat, however, although it’s conceivable he imagined they were.

Jones’ original intentions appear honorable: In the 1950s, he angered conservative members of his Indiana congregation by advocating integration. America was legally segregated at the time according to the provisions of what were known as Jim Crow laws. Among the programs of his own movement, Wings of Deliverance, was work with the homeless. In the early 1960s, he served as director of Indianapolis’ Human Rights Commission. Then Jones seems to have had a vision. It’s thought that an Esquire magazine story on December 6, 1961, caught his eye. It reported that a survey of nuclear war dangers had indicated that the Californian town Eureka was one of the safest places in the world. Jones moved his family and his congregation to Redwood, just over 100 miles away from Eureka, in 1965. Later, in 1971, he transferred 26 miles north to San Francisco. Wings of Deliverance had by this time become the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ.

Exactly when the inspiration occurred isn’t clear, but shortly after his arrival in San Francisco, Jones seems to have become acutely aware that only a physical separation from America would suffice. Then in his early forties, Jones seems to have decided the struggle for equality and citizenship was futile given the institutional arrangements in the US. There were several racist-motivated uprising, or riots as many called them during 1970-73, from New Mexico to New Jersey.

There was also a major crisis over the schooling of black children, many of whom were “bused” — transported to a school where a children from other ethnic groups were predominant in an attempt to promote integration. The surge of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1960s died away in the next decade, though the racist organization aligned itself with neo-Nazi movements. David Duke, who was later to become the Klan’s grand wizard, in 1970 formed a student movement called the White Youth Alliance. There may also have been a more prosaic reason for Jones’ decision to leave the US: There were rumors of his misappropriation of church members’ money — only rumors.

The more compelling argument is that Jones had some kind of epiphany and discovered he could affordably buy land in the rain forests of Guyana, a country with a population of less than 800,000 at the time, which was settled by the Dutch in the 17th century and occupied by the British from 1796, until independence in 1966.

Peoples Temple

In 1977, over 1,000 acolytes followed Jones and started building the new settlement. There was no coercion; Jones, it seems, was spellbinding. He told his disciples to work long hours, obey his commands and mistrust anyone apart from him. This included fellow Jonestown residents. Despite efforts to restrict communication with the outside world, accounts of wrongdoing filtered back to the US, particular San Francisco, where Jones was once based. Leo Ryan, a California congressman, felt concerned enough to launch an investigation and, in November 1978, flew to Guyana with 17 relatives of Jonestown settlers and a media delegation.

Ryan reached Jonestown but was never allowed to return. The visit appears to have gone without significant problems at first, though Ryan, it seems, was accosted by a Jonestown resident. While boarding a plain bound for the US, Ryan was shot dead, along with the other members of the delegation — presumably at Jones’ behest. The disaster then took an even grimmer turn, when, back at the settlement, Jones gathered his followers, including 200 children, and ordered them to drink a deadly mix of cyanide, sedatives and powdered fruit juice. A total of 909 died, all but two from cyanide poisoning. It was the largest mass suicide in modern history and resulted in the greatest single loss of American civilian life in a non-natural disaster until September 11. Just 87 members of Peoples Temple who were in Guyana survived, the majority because they were away from the settlement on the day.

The scarcely believable news defied rational analysis. The world had become accustomed and perhaps anesthetized to the sight of soldiers being hastened along the road to hell; the Vietnam War had ended only three years before. Perhaps the Korean War held more clues: It was thought that China’s communists had learned how to penetrate and control the minds of American prisoners of war. The technique was called “brainwashing,” and it was suspected Jones might have perfected this to the point where he was able to construct a totalitarian state where his followers were as pliant as Pavlov’s dogs. Much the same simplistic explanation was employed to comprehend the behavior of Charles Manson’s followers, who carried out a series of murders, including that of actor Sharon Tate, in 1969.

Jonestown provided a perverse template for later religious movements. In 1994, devotees of Joseph Di Mambro followed his example and committed suicide in an attempt to “Escape the world to a higher dimension.” The remains of a total of 74 members of what was known as the Order of the Solar Temple were found in Canada, Switzerland and France.

A similar form of demagoguery was afoot in Heaven’s Gate, a movement based in San Diego, under the leadership of Marshall Applewhite, who interpreted the arrival of the Hale-Bopp comet, which passed close to the Sun in the spring of 1997, as a sign of the apocalypse and a cue to leave the “human world.” Thirty-eight disciples believed him and consumed lethal amounts of poison in applesauce.

Solar Temple and Heaven’s Gate undermined any thoughts that history couldn’t repeat itself. There’s no evidence that their followers were inspired by anything remotely like Jones’ vision of a race-free utopia — if, indeed, that’s what he promised. But we know they were all reared in a world where the appeal of remembrance or impending ideal can make many prioritize a vanished past or promised future over the immediacy of the present.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.