The sitcom format may have had its heyday, but in recent years it has enjoyed a revival, with new and complex twists.

Back in the eighties and nineties sitcom entertainment was one of the major early evening television entertainments on the big TV channels. Popular series like “The Cosby Show”, “Married…with Children”, “The Golden Girls”, “Who’s the Boss?”, “Home Improvement”, “Roseanne”, “Seinfeld”, “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” or “The Nanny” were the canon of TV shows to know. The series shared several features which revealed their specific genre as soon as you switched on the TV and watched just a couple of minutes: the setting of the events normally consisted of one or two rooms in a residential house (most commonly its living room and kitchen), which served as the general meeting point for the inhabitants. The typified characters were the members of the residential (upper) middle class family, consisting of a father, mother, 2-3 children (although, like in the Cosby family, this number could reach up to five), sometimes including cousins, aunts, uncles or the older generation of a grandfather or grandmother. A variation of this setting could be that the plot was taking place in the flat of a circle of friends who stood in close or special relation with their neighbors. Additionally, the shows could easily be identified by the studio setting with mostly multi-camera setup and – if no real audience was present – an added laugh track to support verbal jokes or physical slapstick. Although a general storyline and ongoing characters were featured, every episode was more or less self-contained and the overall plot was rather simply structured, so no previous knowledge was necessary to understand the ongoing events and enjoy the show. Conflicts were built up and solved during one 22-minute long episode and only some sitcoms used story arcs to develop an issue over a longer time span. Typical issues to deal with were juvenile love which had to be restricted by parental supervision, other love affairs, inner-familial conflicts, social events like visits to the theatre or from distant relations, monetary issues, school work or other everyday problems of minor significance.

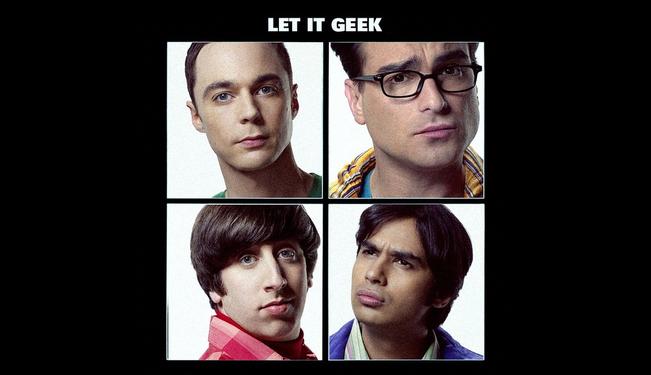

Although several of these traditional elements can still be found in contemporary series and several sitcoms still work the same way as their precursors from the 20th century do, two exceedingly popular shows break through this well-known form of using stock family characters, stereotypic plot elements and commonplace themes. Warner Bros.’ “The Big Bang Theory” and 20th Century Fox’s “How I Met Your Mother”, both broadcasted by CBS in the US and Pro7 in Germany, tread slightly, or rather fairly, different paths in storytelling, and thus introduce a “new complexity” in situation comedy. While the two series do not work in the same way, both are using new forms of comedy. They both have special features which make them appealing to a rather intellectual clientele.

“How I Met Your Mother”, running in the US since 2005 and in Germany since 2008, has been and still is one of the most popular sitcoms today. This is documented by the huge number of awards it has been nominated for and has won since the start of its first season: besides Emmies, one Golden Globe and several nominations, this year the show won (amongst others) the People’s Choice Award for the “Favorite TV Comedy” in the US – although it has already been on air for 7 years. So what exactly is it that makes this show so immensely popular?

The most striking feature of this comedy show is its playful use of narrative strategies. In contrast to other sitcom series, the narrative arc is not merely a minor element, but one major feature of the plot: as the series’ premise is that Ted Mosby is telling his kids the story how he met their mother, one of its basic features is that the audience does not know who she is and that the mystery is not going to be solved until the final season(s). This form of plot is a tricky combination of two ways to create suspense in a narrative: first, the synthetic structure by which suspense is steadily built up by who Ted is finally going to meet and marry; and second, the analytical procedure of explaining how it has come to the point in the future where the story begins. In a series of flashbacks, Ted’s past is revealed bit by bit and it soon becomes clear that meeting the mother is not the most important part of the story, but rather all the experiences Ted and his friends had when they were young.

But this overall structure is not the only thing adding to the complexity of the narrative form of the show. Even within each single episode the story is rarely told in a chronological order: mostly, the audience has to reconstruct the storyline by cognitively rearranging the events because of frequent flashbacks and flash-forwards. Sometimes important information is left out by explicit ellipses (for example, when Ted has to drink five Tequilas, blacks out and wakes up in the morning with an unknown girl in his bed and a pineapple on the table; here, Ted and the audience together have to find out what happened, piecemeal); sometimes multiple perspectives of different characters tell completely different stories of the same event, showing that the characters’ memories are not always as reliable as they would wish them to be (e.g. if Ted and Lily really made out in their first year at university); sometimes events are told differently from how they must have taken place, showing that narrators are deliberately not always sticking to the facts (for example when Ted calls marijuana joints “sandwiches” in order to protect his kids’ innocent minds). So both the overarching storyline and each individual episode demand a great deal of attention and cognitive effort of the audience to follow the story that is told. This is enhanced by the careful construction regarding plot and characters: tiny details which are mentioned in one episode are not dealt with until they fit the story and turn up only weeks later (like the episode with the goat: it is not explained why the goat was standing in the bathroom until several episodes later) or marginal character traits are developed further and further over a long period of time (like Robin’s former success as a 90s teenage pop star in Canada). Thus the major elements of comedy in this show consist of its cleverly devised plot construction and its richness in detail, both of which cannot be appreciated by watching only one episode. This creation of humor sets itself apart from the low comedy of older series that mostly drew on verbal and physical jokes. A cliffhanger using Barney’s running gag line “It will be legen- wait for it, wait for it -dary” split into two halves between two whole seasons as artificial plot device shows the witty narrative construction of the series which surely has a lot of surprises to come.

Another form of complexity can be traced in “The Big Bang Theory” which – just like “HIMYM” – has had awards heaped on it since beginning in 2007 (and 2009 in Germany). Besides nominations and awards in major categories, the show’s lead actor Jim Parson has won awards frequently (in 2009, 2010 and 2011). This points to why this show is so popular: here, it is not the narrative structure of the discourse which is the most crucial thing, but the characters. The dramatis personae deviate from the ordinary circle of people presented in these shows: families or circles of friends which are average men, women, teenagers and children from the social and intellectual middle class. In “TBBT” these are replaced by a group of young scholars who are praised for their high IQ and outstanding achievements in science (even the hard sciences physics and mathematics). Although the characters get a flavor of mediocrity when depicted as “nerds” who are not able to talk to women (Rajesh), to stick to or understand social norms (Sheldon), to move out of their mother’s house (Howard) or who heavily suffer from lactose intolerance (Leonard), the thematic orientation of the series strikes as being highly intellectual and sophisticated. In the pilot episode for example, Leonard and Sheldon compete for attention of their new neighbor Penny by showing her their complicated calculations of a difficult physics problem. On their home blackboards they show off their work on quantum mechanics and string theory, and Sheldon explains to her his spoof of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. Similar to Penny, most of the audience probably cannot follow their explanations but gain amusement from this complexity. So, although the characters come from a very exclusive social group of people and use a very elaborate code of communication, the setting in this social environment seems to work perfectly, precisely because of the audience’s comical distance to the character’s behavior.

But not only the professional discussions add to the elaboration of the show’s content: even in their “nerdiness” the characters are highly intellectual when talking about comic books, blockbuster movies or computer games, normally seen as low culture products. A complex net of intertextual references – i.e. quotations or analogies referring to former “texts” like comics, films or computer games – adds to the comic effects the series achieves by wordplay or slapstick (for example, Sheldon’s obsession with Mr. Spock or Sheldon and Leonard’s guess that William Shatner holds the record for being named “People magazine’s sexiest man alive”). This intertextuality is at its peak in the episode where the characters find the one ring from Peter Jackson’s blockbuster movie “The Lord of the Rings” (which means they find one of the props used in the production process of the film). This episode becomes highly meta-fictional, because the boundaries of the series reality blur with the meta-level of the fantasy film: the guys act exactly like the characters in “The Lord of the Rings” do. Like Smeagol and Boromir, the nerds fight for their ring and Sheldon even turns into Smeagol in his dreams. This form of complexity emerges mostly from the contextual knowledge of the audience. Without it, the jokes would be senseless. Thus again, a certain degree of general knowledge is the precondition to create comic effects.

These two examples of a “new form” of the sitcom genre show developments found in postmodern texts evolved during the 20th century. The emphasis of achronological discourse, multiperspectivity, unreliable narration, intertextuality, anti-heroes as characters (Sheldon/ Barney) are all features prominent in postmodern (often high culture) texts. Maybe these two entertainment TV series show the permeation of complex, form-sensitive structures into a medium and genre which for a long time has not been regarded as the beacon of good taste and high culture. But, as in postmodern times the borderline between high and low culture has started to dissolve, this development only shows what we have already stated on an intellectual level, but have lacked to admit in everyday life: that high and low culture cannot be differentiated at all – not even in ordinary TV entertainment today.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment