How nice it would be to continue pretending that Trump didn’t win in November.

Two days before the November elections, Elizabeth Moreno was driving to the Democratic Party headquarters in Manassas to pick up a list of addresses. She was planning to spend another day of canvassing to get out the vote for her candidate Hillary Clinton. Elizabeth had taken off a full week from her job at one of Washington’s premier foreign policy thinktanks to devote herself to electing the first woman president. She was only two years younger than Hillary Clinton, but she considered the former secretary of state her mentor. Elizabeth Moreno would do anything to get her elected.

Two blocks from party headquarters, as she was gliding through an intersection, Elizabeth took her eyes off the road to glance at an incoming text on her phone resting in the cup holder. It was the latest polling data giving Clinton a 75% chance of winning the election. Just as she was digesting the good news, a jogger wearing headphones crossed against the light in front of her. Elizabeth, her eyes darting back to the road, turned the steering wheel hard to the right even as she was stepping down on the brake. The car skidded and slammed into a concrete divider.

Four months later, Elizabeth Moreno opened her eyes.

In her hospital room, four people were watching her intently. Her son Alex stood at the foot of the bed, gripping the metal railing. By her side sat her daughter Maggie, holding her hand. A nurse was monitoring the vital signs. A doctor stood back a few steps, arms folded above her stethoscope.

“Mom?” Maggie asked as she watched her mother’s fluttering eyelids. “Can you hear me, Mom?” “She’s going to be confused,” the doctor warned in a whisper. “She might not recognize you.” “But this is good, right?” Alex appealed to the doctor. “She’s can’t slip back into a coma, can she?”

“Mom, it’s Maggie. Your daughter.”

Elizabeth Moreno’s eyes focused on her daughter. She licked her lips, and the nurse leaned over to offer a small chip of ice.

“We don’t want to put any stress on her right now,” the doctor added. “We’re right here, Mom,” Alex said, raising his voice. “You’re going to be okay.”

Elizabeth Moreno sucked on the ice. She blinked several times.

“It’s important that we don’t do or say anything that could upset her,” the doctor was saying in a low voice. She hadn’t initially thought that Elizabeth Moreno would survive the head trauma and the heart attack, not at her age, so she’d been only cautiously optimistic with the children.

Elizabeth focused on her son at the foot of the bed. Then she turned her head slightly to address her daughter. “Hillary,” she said.

“No, Mom, it’s Maggie. Your daughter, Maggie.” “As I said,” Dr. Kim began.

“Hillary,” Elizabeth said again. She raised her head slightly from the pillow. “The election.”

Maggie looked at her brother. Alex looked at the doctor. The doctor looked at the nurse. The nurse looked away.

“Is the election … over?” Elizabeth said. “Did Hillary win?” “We can talk about that later,” Maggie said. Alex tightened his grip on the smooth metal frame of the bed. “Of course, Mom,” he said. “Of course, Hillary won.”

Maggie turned her head sharply toward her brother, a look of horror on her face. But Alex was focused on his mother. “You did good, Mom,” he said and he watched with relief as his mother relaxed back into her pillow and closed her eyes.

Scene Two: In the Cafeteria

“Are you out of your mind?” Maggie asked her brother. They were sharing a cup of coffee and a packaged crumb cake.

“You heard what the doctor said.”

“You lied to her!”

“Didn’t you see that German movie? What was it called Good Bye, Lenin, I think. The mother goes into a coma before the fall of the Berlin Wall and wakes up afterwards. Same situation. Doctor says the kids musn’t do or say anything to shock her. The mother’s a true believer in communism, so her kids have to pretend that East Germany still exists. They have to find all the old food she liked. Dig up some old newspapers. I figure that it’ll be easier for us. All we have to do is pretend that Hillary won.”

“And how are we going to do that? Bring Mom to a silent retreat center in Antarctica? Transfer her to a bunker somewhere and give her nothing but the boxed set of Mad Men to watch?”

“Look, it was the first thing that came out of my mouth,” he said. “I haven’t really thought about next steps. Beyond removing the television from her room.”

“Easy enough for you,” Maggie said. “You’ll go back to Colorado and I’ll be the one who has to tell her the truth.”

Alex patted her arm. “Mom’s a pretty no-nonsense gal. She’s the one who told us that Santa Claus didn’t exist. Dad couldn’t bear the thought of destroying our illusions.”

“Yeah, but we weren’t at risk of having a heart attack when we learned that it was Dad who put the presents under the tree.”

“I’ll stick around for another week. I also know a guy who can get us a lot of that Clinton inaugural swag for next to nothing. We can decorate the apartment.”

“What about her friends? What about the newspaper? What about the internet?”

“It’s not forever,” Alex said. “Just until she can sustain a shock like that.”

“I’m not sure I’ve handled the shock yet,” Maggie said, ruefully. “And I wasn’t in a coma.”

Scene Three: Back Home

“Look at all those women,” Elizabeth Moreno said, gazing at the photograph on Maggie’s iPad. “I wish I could have been there.”

They were sitting together in the living room, Maggie and Alex on either side of their mother’s wheelchair, looking at a selection of carefully cropped photographs of what they told her was the inauguration.

“It felt very empowering,” Maggie said. Here, at least, she was telling the truth. The gathering of a million women in Washington DC on the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration had felt empowering. Just not empowering enough.

Elizabeth raised her head to look at the Clinton mug on the coffee table, the Clinton/Kaine Mylar balloon tied to the standing lamp, the President Clinton bobblehead on the mantle above the fireplace. She felt good about contributing to a great step forward for women, for the United States, for humanity.

But she also felt disoriented. Entering the last days of the election campaign in 2016, Elizabeth had been an energetic 68-year-old who continued to put in 10-hour workdays and play golf on the weekends. She’d lost more than just weight and muscle tone during her coma. Everything that had previously seemed so clear now felt imprecise, fuzzy. Catching a glimpse of herself in the bathroom mirror that morning, she was practically unrecognizable, someone who had aged 10 years in the space of a few months.

“I wish I could at least watch television,” she said in what had become the new normal: The slow, quavery voice that had replaced her confident baritone.

“Not until the ophthalmologist gives the okay,” Alex said. “You don’t like hearing us read the newspaper to you every morning?”

Elizabeth had come home from the hospital three days before. For the first couple days, it had not been difficult to put off discussions of politics until Elizabeth was “more robust.” That morning, however, she’d woken up with something resembling her old energy. She wasn’t satisfied with the expurgated version of the news that her children read to her: “Dow surges to new high” or “Firemen rescue cat from mountain lion.” Alex had come up with the idea of showing her pictures of the “inauguration.”

But now their mother had foreign policy questions, particularly about the Middle East, her specialty. The family had spent four years in Cairo during Elizabeth’s Foreign Service posting in Egypt. Alex and Maggie, both in elementary school, had picked up Arabic, and their father, as they only learned much later after the divorce, had picked up his first mistress. It was yet another reason why Elizabeth felt an affinity for Hillary Clinton.

By pre-arranged plan, since she was a journalist on the State Department beat, Maggie fielded all the diplomatic questions. Alex, a financial planner living in Boulder, would handle economics.

“Has she followed up on the Arab-Israeli peace talks?” Elizabeth asked.

“The United States stood aside in the Security Council when it voted to condemn Israel’s settlement policy,” Maggie said. “Israel was very unhappy.” What she didn’t say was that President Trump’s rejection of a two-state solution, his appointment of a lunatic ambassador, and his decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem amounted to thwacking the hornet’s nest of the Middle East with a big stick. Maggie knew that information about the current state of affairs between Israel and the Arab world would administer an even greater shock to her mother’s system than even Trump’s victory.

“Finally, someone with the balls to stand up to Netanyahu,” Elizabeth said. “Now, what about Syria?”

“A fragile ceasefire is holding,” Maggie said, feeling like a White House spokesperson. Best not to tell her mother how a trio of autocrats—Assad, Putin, and Erdogan—was turning Syria into a wasteland with the blessing of the White House.

“Oh, that’s good,” Elizabeth said. “Is she holding her own with Russia and China?”

“She has pushed back against the neocons who supported her during the campaign,” Maggie said, indulging in a bit of wishful thinking. “You know our Hillary: Ms. Smart Power.”

Certainly she wasn’t going to tell her mother that tensions were building with China over a number of slights and that Trump was burning bridges with Europe over his bromance with Putin. It was so bad that one prominent foreign policy pundit had joked about asking doctors to put him in an induced coma for the next four years. Would her mother regret waking up when she learned the truth?

Elizabeth smiled. “Tomorrow, let’s set up the computer with that voice-activated program. I’d like to hear my emails.”

Alex and Maggie exchanged glances.

“Actually, Mom,” Alex said, “we’ve arranged tomorrow to go out to that Korean spa you love so much. Doctor’s orders!”

In the kitchen, Maggie said to her brother, “Korean spa? Where did that come from?”

“We’ve got to keep her away from the computer.”

“What if she talks to someone? Or sees the TV?”

“We’ll ‘forget’ to bring her glasses. And there’s not going to be anyone there who speaks English.”

“But why the spa of all places?”

Alex grimaced. “Because I need some serious R and R after this charade.”

Scene Four: At the Spa

On the car trip from Elizabeth’s apartment in Dupont Circle to the spa in Virginia, Maggie scrutinized the landscape that streamed by her window. She was the designated spotter. If she saw any sign of Trump’s presidency—a billboard, a poster—she was to engage her mother’s attention before she could see the telltale evidence. They’d failed to prevent her from bringing along her glasses. Their mother was determined to begin her reintegration into society as soon as possible.

Yet there were no external indications of who’d won the November election. Maggie had noticed the opening of a couple new steakhouses, and the Trump hotel downtown was doing brisk business. His appointees had bought up the most expensive houses on the market. But unless you were working in the policy world, you could easily ignore what the new administration was doing. Covering the State Department, however, Maggie had a front-row seat to watch the growing centralization of power, the incompetence of the new appointees, the coarsening of language inside the Beltway. She’d already put in for a transfer to a different beat.

“I don’t know what I expected,” Elizabeth said, staring intently out her passenger side window. “People are just going about their business as if we didn’t just change the course of history.”

At the spa, Alex went directly to the whirlpool while Maggie accompanied her mother to her body scrub appointment. They’d spoken with the management of the spa to ensure that the personnel working with their mother were not fluent in English. At first Maggie had been worried when her mother started asking the Korean woman wielding the loofah about President Hillary Clinton. Middle-aged and powerfully built, the woman just smiled and went about her work rubbing away Elizabeth’s dead skin. After a while Maggie relaxed, and her mother fell asleep.

They met up for lunch in the common room, three big bowls of bibimbap with little plates of Korean pickles. They chose a table far from the TV sets and positioned their mother’s wheelchair so that she faced a wall that had nothing but scrolls of calligraphy.

“I had a great workout,” Alex said, digging into his bowl of rice and vegetables. “How was your body scrub?”

Maggie looked over her mother’s shoulder at a distant TV showing Donald Trump’s face. It was everywhere. How could they hope to protect their mother from it?

“Oh, it was fine,” Elizabeth said. “But I just don’t understand why people are not more excited about Hillary.”

At the aromatherapy appointment after lunch, Maggie was horrified to see that masseuse was not Korean.

“Tatiana,” the statuesque blonde introduced herself. She had a slight Russian accent. “Mrs. Kim had a family emergency.”

Maggie was about to cancel the appointment when her mother stopped her. “I’m sure I’ll be in good hands,” Elizabeth said.

And for the first 15 minutes, Maggie was relieved to see that Tatiana kept her interactions with her mother to a professional minimum. The masseuse was rubbing a mix of essential oils—lavender, peppermint—gently into her mother’s muscles. Elizabeth’s eyes were closed.

Then, without opening her eyes, Elizabeth asked, “How do you feel about President Clinton?”

Before Maggie could react, Tatiana said, “I was not in this country when he was president.”

Elizabeth laughed. “Oh, no, I mean Hillary Clinton.”

Maggie interrupted in a panic, “Mom, don’t put Tatiana on the spot.”

“Why not? I’m sure she has an opinion of the first woman president of the United States.”

Maggie tried to catch Tatiana’s eye, but the masseuse was focused on her work. She didn’t say anything for a long time, and Maggie concluded that she wasn’t going to reply. Then Tatiana stood up straight and wiped her hands on a cloth looped around her belt.

“She did the best she could,” the masseuse said. She took out another vial of essential oil and prepared to go back to work.

That was the end of Elizabeth’s questions, and Maggie was happy that the rest of the session passed in silence.

Later, as they were driving out of the parking lot, Alex asked, “You okay, Mom?”

“Thank you for taking me to the spa.”

“We could get a pizza on the way and bring it home for dinner,” Maggie suggested.

“If you like.”

They rode in silence for a few miles.

Then, Elizabeth said in a small voice, “You lied to me.”

“What are you talking about, Mom?” Alex said, hands tightening on the steering wheel.

“Don’t lie to me, Alex,” Elizabeth said softly. “You either, Maggie. I expect better from you both.”

Neither of them replied. The silence hung heavy in the car.

“I was in a coma for four years,” Elizabeth said. “Not four months.”

“What?!” Maggie blurted.

“The Russian woman. She said that Hillary did the best she could. I must have missed the whole Hillary Clinton administration!”

“Mom, wait, we wouldn’t …” Alex began. Without taking his eyes off the road, he dug his phone out of his pocket and passed it to her. “Look at the date. It’s still 2017.”

Elizabeth stared at the phone for a long time. Then she let her hand fall to her lap.

“Your email,” she said.

“What about my email?” Alex asked.

“There were several messages about President Trump.” Elizabeth made a small choking sound. “She lost.”

“Oh, God,” Maggie said.

Alex pulled off the road and into the parking lot of a bank. They all sat quietly.

“That German movie,” Elizabeth said.

“You saw it?” Maggie asked.

“This is different,” her mother said, wiping her eyes with a Kleenex. “This isn’t about getting used to an irreversible reality, like the collapse of East Germany.”

“Yes, but—” Alex began.

“You want me to get stronger, don’t you? You want me to get my fighting spirit back, right?”

Her children nodded.

“Then we can’t stick our heads in the sand and pretend that we didn’t just elect the worst candidate in the history of this country.”

“We were just doing what we thought was best for you,” Maggie said.

Elizabeth took a deep breath. Her heart seemed to beat as before. She was feeling more clearheaded than she had in days. “I have a lot of catching up to do.”

“But the doctor—” Alex began.

“Doctors are as bad as pollsters. I don’t intend to listen to either of them ever again. Let’s get that pizza and go home. We have a lot of work to do.”

Elizabeth sank back into her seat.

“Goodbye Clinton,” she whispered to herself.

*[This article was originally published by FPIF.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

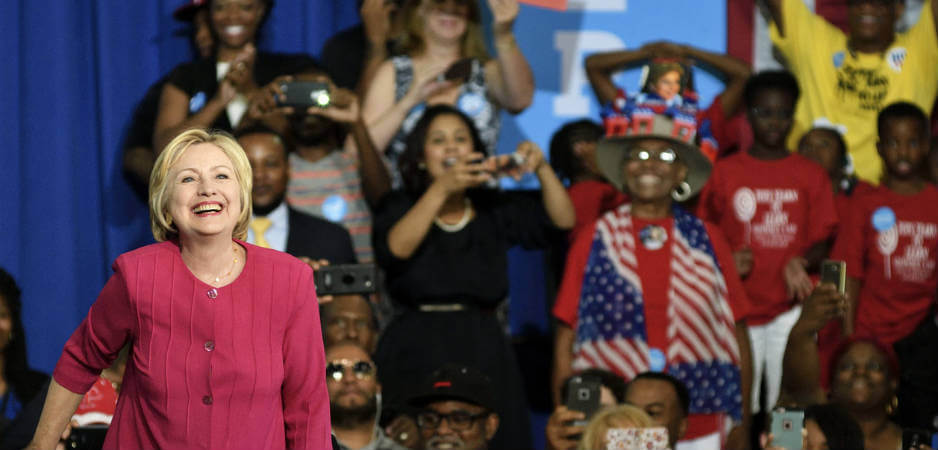

Photo Credit: BasSlabbers

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.