Our shared perception of Magna Carta owes more to events in the 17th and 18th centuries than the 13th.

English history is full of myths. That shouldn’t surprise us, because a large part of modern English national identity is based on what we collectively believe happened in the past, rather than on what actually did—at least, as far as we can tell.

The job of historians becomes harder still when there are fewer sources to deal with. It’s also challenging because the sources we do have come loaded with their own sets of problems. Bias, of course, is the best known. But there are others too.

Unfortunately, Magna Carta has several myths attached to it. Here are six of the most common, explained.

It Wasn’t Necessarily About Rule of Law

With Magna Carta, what we are essentially celebrating is the triumph of the rule of law over arbitrary power. Whether that power was abused by monarchs, heads of state or politicians amounts to the same thing.

This view has a long history. And it’s best expressed, I think, by an anonymous pamphleteer who saw himself as the voice of the people: Our ancestors had paid a heavy price in blood over hundreds of years to wrest these concessions from the crown, but what they got was part of their birth-right—namely a “brazen wall, and impregnable bulwark that defends the common liberty of England from all illegal & destructive Arbitrary Power whatsoever.”

Yet it’s telling that this quotation comes from 1646, during the height of the English Revolution. Because an appeal to this “Charter of our liberties” reveals how a particular sense of the past was used to great effect in contemporary political struggles at a crucial moment when parliament’s armies had defeated the royalists on the battlefields of England and Wales, but the way in which the kingdom would be governed was still up for grabs.

Indeed, I’d go further and suggest that the popular view of Magna Carta largely derives from the ways in which it was mythicized during these 17th century conflicts—first between parliament and the early Stuart monarchy, and then between those on the winning side.

It Wasn’t All About 1215

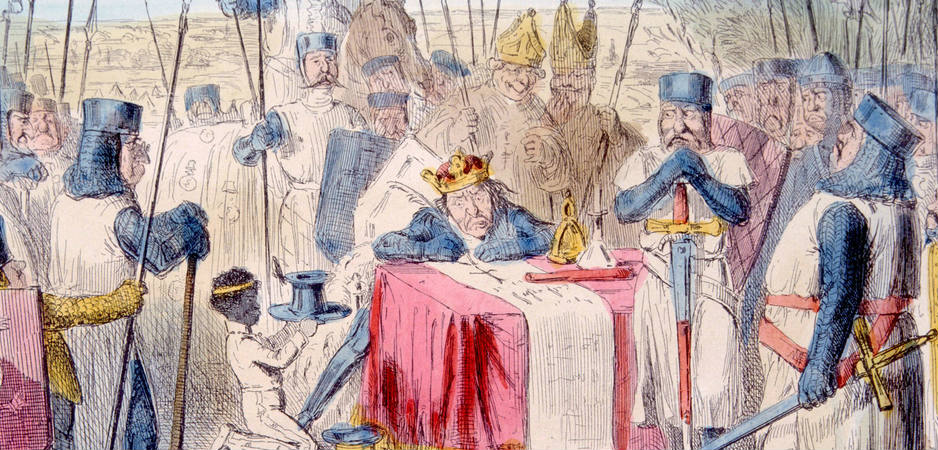

First, the facts: On June 15, 1215, King John granted a series of concessions to his rebellious barons at Runnymede. A formal royal grant based on these agreements became known as Magna Carta. But following John’s death in October 1216, and the accession of the child Henry III, the “Great Charter” was reissued by the regent with several significant modifications and omissions.

These changes restored a number of powers to the crown, including the right of taxation. Further changes were introduced in 1217, and again in 1225, when the original 63 chapters were reduced to 37. In 1297, Magna Carta was reconfirmed by Edward I, who directed his justices to administer it as common law.

Although the provisions of the charter became antiquated with the passage of time, they still remained in force. Indeed, they were seen as representing a fundamental and inalienable aspect of the law.

The Document Wasn’t Always Iconic

The transformation of Magna Carta from an important document into an iconic one was mainly the achievement of one man: the jurist Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634).

It was during a parliamentary debate in 1628, about mooted limitations to the Petition of Right—another landmark legal concession gained from the Crown—that Coke declared “Magna Charta is such a Fellow, that he will have no sovereign.” According to Coke, the charter functioned as the king’s conscience to check tyrannical impulses. Charles I understood this, and so prevented publication of Coke’s exhaustive commentary on the Magna Carta.

Consequently it remained in manuscript during the author’s lifetime, and it was issued posthumously by order of the long parliament (the English parliament summoned in November 1640 by King Charles I) as the first exposition of The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (1642).

All the same, it’s worth emphasizing that the charter Coke revered was not the original of 1215, but the amended 1225 version.

Not Everyone Regarded the “Grand Charter” as Every Englishman’s Legal Birthright

Coke’s views influenced a number of prominent lawyers. Echoes of them can be found in the writings of John Lilburne, an irrepressible, argumentative radical whose political movement—the Levellers—would be defeated, but whose ideas are still celebrated today.

Initially, Lilburne regarded the “Grand Charter of England” as every Englishman’s legal birthright and inheritance; a binding contract purchased by a sea of blood that maintained the boundary between sovereignty and subjection.

His enthusiasm, however, was to be tempered by the arguments of another future Leveller, William Walwyn. In an open letter addressed to Lilburne, published as Englands Lamentable Slaverie (1645), Walwyn warned that Magna Carta was misnamed: It was a deceitful and improper term to blind the people.

For Walwyn the charter constituted just an aspect of the people’s rights and liberties that had been wrestled out of the paws of kings. Drawing on another potent myth—that ever since the Norman Conquest the English people had lived under the weight of an arcane, burdensome and expensive legal system (the so-called “Norman yoke”)—he dismissed Magna Carta as but “a beggarly thing, containing many marks of intolerable bondage.”

Accordingly, Lilburne conceded that the great charter fell far short of the laws enacted before the conquest by Edmund the Confessor.

It Didn’t Necessarily Guarantee Trial by Jury to All Englishmen

Yet there remained something worth championing: the 29th chapter of the charter of 1225 (clause 39 in the original). For these few words, thought Lilburne, embodied “the liberty of the whole English Nation”: “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or disseised of his Free-hold, or Liberties, or free Customes, or be out-lawed, or exiled, or any otherwise destroyed: nor we will not passe upon him, nor condemne him, but by lawfull judgement of his PEERES, or by the law of the land.”

Coke’s reading of this clause had upheld the principle that commoners could only be convicted by their fellow commoners, or according to the law of the land. Lilburne agreed, citing this interpretation when brought before the House of Lords (he claimed that he could not be tried by peers of the realm, since they were not commoners).

It’s since become customary to read chapter 29 of Magna Carta as guaranteeing trial by jury to all Englishmen. As was pointed out in scholarly work to mark the 700th anniversary of the charter, however, the traditional interpretation needs to be modified. This is because the original Latin wording is ambiguous. Indeed, Coke’s interpretation was anachronistic, since he viewed early 13th-century law through a 17th century lens. If anything, this famous clause confused, rather than clarified, matters.

After all, judgment by peers or by the law of the land was not the same as judgment by peers according to the law of the land.

It Wasn’t Just an English Charter

The English Revolution may have ended in failure with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. Yet some of its dynamic ideology was transplanted to North America—both immediately and eventually, by way of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89.

When the American colonists came into conflict with the British crown, they drew on this heritage in their impassioned rhetoric. So we find the Stamp Act of 1765 denounced by the Massachusetts Assembly as being “against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen.”

And the great charter was invoked again in 1779 by John Adams, who would later become second president of the United States: “If, in England, there has ever been such a thing as a government of laws, was it not magna charta? And have not our kings broken magna charta thirty times?”

Even today, prominent legal historians have noted that Magna Carta continues to be widely cited in American judicial opinions—notably in the right to trial by jury; in the right to speedy and adequate justice; and on the question of proportionality in punishment.

Certainly, then, there is much to celebrate on the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta: namely vestiges of the 1215 charter that were incorporated into subsequent versions. But we should also accept that our shared perception of Magna Carta owes more to events in the 17th and 18th centuries than the 13th.

*[This article was originally published by BBC History Magazine.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Everett Historical / David Smart / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment