| ||

| ||

| ||

Dear FO° Reader, As our homes in Switzerland and Washington, DC, combat the last month of frigid autumn weather before winter, conditions across California continue to make us jealous. With that said, Canada’s largest province, Québec, is attempting to defy natural law with its own unprecedented political heatwave. On October 9, 2025, the government of conservative, Québec-native Premier Francios Legault tabled a new draft constitution, which some liberal readers called political theater on paper. While advocating for secularism, gender equity and abortion rights, among others, are not what make this copy extreme, its resentment toward Canadian multiculturalism as well as English monarchical rule certainly does. Sources: Quebec Constitution Act of 2025 – National Assembly of Quebec 2025 Constitution Act overview – The Canadian Press Liberal view of 2025 Constitution Act – CBC News Prejudiced components of the 2025 Constitution Act – Policy Magazine of Canada Local support of these controversial tenets has started to rekindle a cause dormant for almost five decades: Québec’s independence. Despite its central location in the country, several natives suggest their language and culture have been slowly cast aside over many years, risking complete erasure if like-minded legislation is not soon accommodated.

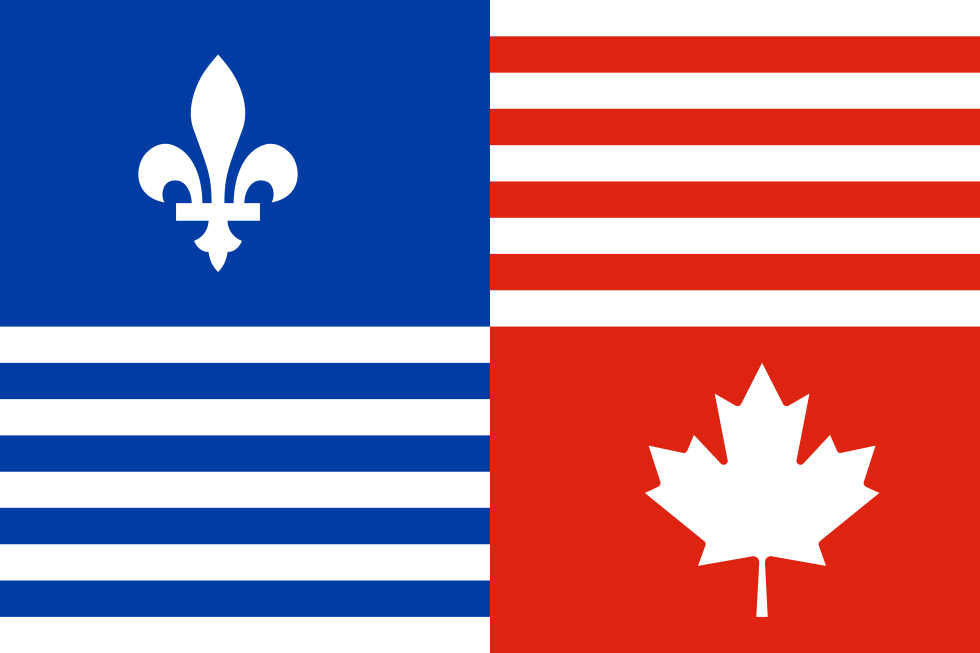

Graphic representation of the Canadian and Québécois flags. Sources: Why youth support Quebec’s independence – France24 The narrow passage into a new world On July 3, 1608, French explorer Samuel de Champlain founded a North American settlement along the St. Lawrence River that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean toward four of the inland Great Lakes. Named “Kepek,” an indigenous Algonquin tribe phrase that referenced said “narrow passage,” but later rendered as Québec of New France, became a valuable trade destination well into the next century. Sources: Biography of Samuel de Champlain – Canadian Museum of History Founding of Quebec City – Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, Canada St. Lawrence river and seaway – The Great Lakes Commission Origin of the name – Canada.ca Epicenter of trade – National Geographic The cost of rights and war Nonetheless, this vast economic gateway, stretching from northeastern Québec to the eventual southwest city of Windsor, Ontario, would promise France no extensive peace. Growing English territory beyond Canada’s present-day Newfoundland and Labrador province, King Charles I handedly defeated troops for the territory in 1629, but returned it to French King Louis XIII during the fall of 1632, after signing the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Sources: English settle in Newfoundland – Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, Canada Fall of Quebec – The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum Biography of King Charles I – The Royal Family Biography of King Louis XIII – Palace of Versailles Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye – The Canadian Encyclopedia As English lands continued expanding, however, concessions in this pact would only last so long. By 1759, the global Seven Years’ War (1754-1763) had driven British colonists to seek sanctuary in the French-controlled Ohio River Valley, but they met swift resistance from the indigenous Algonquin and Huron tribes. After learning that similar partnerships could help them challenge France, Britain allied with the massive Iroquois Confederacy, resulting in the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Sources: French and Indian War/Seven Years War, 1754-1763 – Office of the Historian, US Native American involvement with French and British – Milwaukee Public Museum Following their defeat, France again relinquished authority over Québec to England, signing the Treaty of Paris in 1763. While this agreement likewise gave Britain majority control of French holdings across the region, colonialists fortunately did not prohibit Québécois from using their own language and religion, as guaranteed by the Québec Act of 1774. Sources: The Treaty of Paris, 1763 – The Avalon Project The Quebec Act of 1774 – UK Parliament These appeasement policies were more likely strategic than diplomatic, though. As British troops may have feared a French uprising inspired by the 1775 American Revolution, such legislation certainly did better to keep even more radical Québécois emotionally content. French-Canadian tolerance for English rule would, regardless, be tested again under the Constitutional Act of 1791, further reducing Québec’s domain to Lower Canada, while Ontario remained susceptible to British mediation in the country’s upper half. Sources: Canada and the American Revolutionary War – Museum of the American Revolution Constitutional Act of 1791 – Legislative Assembly of Ontario Turning over a new leaf Notwithstanding this contemporary blow to nationalist pride, Canada’s economy began to gradually flourish into the next century of colonial oversight. Partially stimulated via British demands for timber during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and the development of a public railway system, the country was on a fast track toward self-governance, which it finally secured through the 1867 British North America Act. Sources: Effect of Napoleonic Wars on Canada – The Canadian Encyclopedia British North America Act, 1867 – Government of Canada Adapting to this new autonomous responsibility was no easy task in the twentieth century, however. Since many older conservative Québécois promoted an insular, anti-abortion state whose government was one with the church, a majority of younger liberals would not be submissive in opposition. When left-leaning Jean Lesage was elected as Premier in 1960, he became an inadvertent patriarch of Québec’s Quiet Revolution (1960-1970) for change and wasted no time in office. Ensuring the availability of government-subsidized healthcare, secular education and state-owned power companies in just four years, Lesage redefined the strength of his state. Sources: Divorce in Quebec, 1841-1968 – The Government of Canada The Quiet Revolution – Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages Biography of Premier Jean Lessage – Dictionary of Canadian Biography Wishing you a thoughtful week, Nick St. Sauveur and Team Assistant Editors | ||

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news

must

be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and

editors cost money.

So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

| ||

| ||

| About Publish with FO° FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact |

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment