Some trade economists argue that moderate tariffs, when carefully calibrated, can enhance national welfare within specific limits. Tariffs increase domestic prices of imported goods and potentially create distortions by reducing import volumes and raising production costs for domestic industries. However, an optimal tariff rate can improve a country’s terms of trade by encouraging foreign suppliers to lower their export prices in response to the tariff. This analysis suggests that for the United States, an optimal tariff rate might be around 20%, with diminishing welfare gains observed beyond 50%. Thus, raising current low tariff rates closer to 17% could, in theory, improve US welfare by capturing terms-of-trade benefits, provided trading partners do not retaliate with their own tariffs.

The desire to reform the global trading system and establish fairer competition for American industries has been a cornerstone of President Donald Trump’s agenda, rooted in decades of advocacy. The current international trade and financial systems are on the cusp of generational change, with structural economic imbalances driving the need for reform. At the heart of these imbalances lies persistent dollar overvaluation, driven by the inelastic global demand for reserve assets. This phenomenon prevents the natural balancing of trade and imposes disproportionate costs on the US manufacturing and tradable goods sectors, which bear the brunt of financing reserve asset provision and defense commitments.

The optimal tariff argument seems to provide a strong justification for current trade policies, but it rests on critical assumptions that may not align with modern trade realities. These models often assume symmetrical trade, where exports are not used as intermediate goods in production. They also downplay the role of services in international trade. However, these assumptions overlook key dependencies in global supply chains, such as the US’s reliance on Chinese graphite and germanium for electric vehicle (EV) production. Without access to these essential inputs, producing EVs domestically becomes a significant challenge, exposing a critical gap in the argument. This highlights the importance of considering the interconnected nature of modern trade and the potential unintended consequences of protectionist policies.

Historic use of tariffs in US economic policy

The US has a long history of using tariffs as a tool for economic protection and policy, with notable examples being from the administrations of President William McKinley and President Herbert Hoover. McKinley’s Dingley Tariff Act of 1897 was designed to protect American industries during a period of rapid industrialization by imposing the then-highest tariffs in US history. The goal was to shield domestic manufacturers from European imports and foster economic growth within the country. This protectionist approach reflected the broader economic priorities of the late 19th century, where tariffs were a central strategy for supporting emerging US industries and securing economic independence.

Similarly, Hoover’s Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 was another significant moment in US tariff history, though its consequences were far more controversial. Enacted during the early years of the Great Depression, it raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to protect American farmers and manufacturers from foreign competition. However, this policy backfired by triggering retaliatory tariffs from other countries, leading to a collapse in international trade and exacerbating the global economic downturn.

Decades later, Trump’s first administration revived protectionist policies through tariffs, particularly targeting China, to address trade imbalances, intellectual property theft and currency manipulation. While Trump’s trade war was framed as a modern and bold strategy, it echoed these historical precedents, demonstrating that tariffs have long been employed as tools for economic protection and negotiation in US policy.

Dollar trends and fluctuations

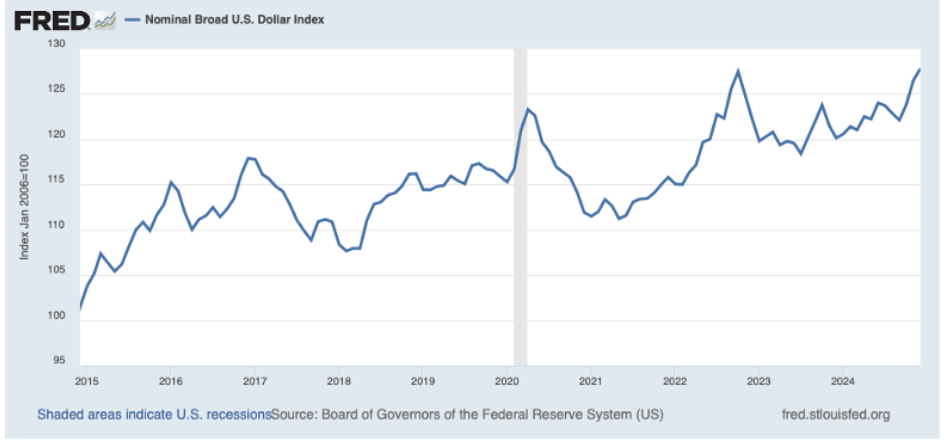

From 2008 to 2023, the US dollar experienced significant fluctuations driven by global crises, monetary policy shifts and geopolitical events. During the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the dollar strengthened as a safe-haven asset despite deflationary pressures. From 2008 to 2014, the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programs initially weakened the dollar before it rebounded in the mid-2010s, due to the US economy recovering more strongly than others.

From 2016 to 2020, the dollar saw notable volatility; the DXY index peaked at 103 in early 2017 after the US presidential election but weakened later that year as global monetary policies tightened. It regained strength in 2018, supported by Fed rate hikes, and remained stable in 2019 with the DXY around 96–98 amid trade tensions and steady growth. In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic caused the dollar to surge above 102 as a safe-haven asset, though it declined to 89 by year-end due to aggressive monetary easing.

By 2021, the DXY started near 89–91, strengthened to 96 by year-end amid Fed tapering signals. It peaked at 114 in September 2022 following rapid Fed rate hikes to combat 9.1% inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), in June. The dollar retreated to 103 by late 2022 as inflation cooled. In 2023, as rate hikes slowed, the DXY fluctuated between 100 and 105 amid improved global conditions, with brief volatility caused by US debt ceiling concerns.

Nominal Broad US Dollar Index (2015–2024). Via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

How tariffs drive inflation

The Trump administration’s trade policy marked a significant shift toward protectionism, with the imposition of tariffs on imports from key trading partners, most notably China. These tariffs were implemented under the guise of reducing trade deficits, protecting domestic industries and addressing unfair trade practices. By increasing the cost of imports, tariffs had a direct inflationary effect on goods that were either fully imported or relied heavily on imported components.

For example, a study by Amiti, Redding and Weinstein found that nearly the entire cost of the tariffs was passed on to US consumers and businesses in the form of higher prices. Consumer electronics, household goods and agricultural products were among the sectors most affected. Import-reliant companies faced increased input costs, which they often passed on to consumers. The inflationary impact was particularly pronounced for goods with limited domestic substitutes, such as specialized machinery or certain agricultural products.

The term “absurd inflation” might be hyperbolic in describing the overall economic picture during the Trump administration. However, it is applicable when considering specific cases where tariffs led to highly disproportionate price increases. Households reliant on tariffed goods bore the brunt of these effects. Studies estimated that tariffs cost the average US household between $800 and $1,200 annually during this period. According to the US Census Bureau, the median household income in the US was approximately $68,700 in 2019, so the cost of tariffs to US households was between 1.2% and 1.7% of annual income.

The mitigating effect of dollar strength

The dollar’s value during this period acted as a counterbalance to the inflationary effects of tariffs. The dollar maintained relative strength against other currencies, partly due to favorable interest rate differentials and the perception of the US economy as a safe haven. A stronger dollar makes imports cheaper, offsetting some of the cost increases caused by tariffs. However, the extent of this mitigating effect varied across sectors and depended on the elasticity of demand for specific goods.

For instance, while the strong dollar helped temper price increases in consumer electronics, where global supply chains are diverse, its effect was less pronounced in agriculture. Retaliatory tariffs imposed by China on US agricultural exports, such as soybeans, primarily reduced farmers’ revenue by making their products less competitive in the Chinese market. However, these tariffs also disrupted supply chains, forcing farmers to find alternative markets or adjust production strategies. These disruptions amplified costs for farmers through increased expenses for storage, transportation to distant markets, and inefficiencies in production. In turn, these elevated costs contributed to higher food prices domestically.

Considering the impact of US dollar strength on inflation, estimated at 40–70 basis points, tariff effects on CPI would range between 0.3% and 0.6%. Annual inflation, as measured by the CPI, ranged from 1.3% to 2.3% during the period 2016–2020. Under stable economic conditions, such modest increases are likely to be temporary, not leading to sustained inflation. Real prices remain unchanged, but weaker exporting-country currencies reduce their real wealth and purchasing power. American consumers’ purchasing power is unaffected as tariff effects offset currency movements. If fully adjusted, the US government could generate revenue from tariffs without triggering inflation, although exports may suffer. Policymakers could partially mitigate the adverse effects on exports through aggressive deregulation.

Impact of tariffs and currency depreciation on inflation

A comparative lens further illustrates the interplay between tariffs, currency value and inflation. Countries with weaker currencies relative to the dollar experienced heightened vulnerability to US tariffs. For example, emerging economies reliant on exports to the US faced not only diminished demand but also increased costs for imported goods priced in dollars. Conversely, US trading partners with stronger currencies, such as the Eurozone, found it easier to absorb some of the tariff-related shocks.

Inflationary effects from currency adjustments can be significant. The International Price System shows that a 20%-dollar depreciation raises CPI inflation by 60–100 basis points. If deemed transitory, the Fed might treat this as a price-level fluctuation. However, if it permanently affects inflation rates, the Fed may raise overnight interest rates by 100-150 basis points under standard Taylor Rule guidelines.

The tariff-dollar nexus: balancing trade and geopolitics

The dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency is central to international financial stability. However, this status also leads to sustained overvaluation, which widens trade deficits and imposes costs on US manufacturing and tradable sectors. Potential solutions include integrating the dollar into a broader adjustable currency basket or promoting the multipolarization of the international reserve currency system. These reforms could mitigate excessive reliance on the dollar and correct distortions in the US economic structure.

Prolonged trade deficits can undermine US national security. Declining strategic industries heighten supply chain vulnerabilities and reduce economic resilience in crises. Policies supporting domestic production in critical sectors and reducing external dependencies are necessary. In light of threats from geopolitical rivals such as China and Russia, the importance of a robust and diversified manufacturing base has been reaffirmed. National security depends on maintaining supply chains capable of producing essential weapons and defense systems.

The relationship between tariffs and the dollar reflects a complex interplay of trade policy, monetary strategy and geopolitical considerations. Advocates like Stephen Miran, a current member of the Council of Economic Advisers under Trump and a senior strategist at the hedge fund Hudson Bay Capital Management LLC (2024) argue that tariffs can correct the overvaluation of the US dollar, address trade imbalances and strengthen domestic industries. A devaluation of the dollar, achieved through currency and bond market interventions, could complement tariffs by making US exports more competitive globally.

However, such policies carry significant risks. Tariffs, particularly those applied in a “beggar-thy-neighbor” manner, can provoke trade retaliation and disrupt global economic stability. The Fed may need to intervene in bond markets to manage the inflationary and interest rate pressures resulting from such strategies. Furthermore, leveraging defense alliances — formal agreements or partnerships between the US and other countries to provide mutual security and military cooperation, such as NATO or bilateral defense agreements — to enforce economic policies could undermine global trust in US commitments, with implications for both economic and geopolitical stability.

Balancing currency policy and trade policy

If a currency agreement were reached, the removal of tariffs would likely act as a powerful incentive for trade partners to cooperate. A critical element of such an agreement would be securing the Fed’s voluntary participation under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). Historically, the Fed has deferred to the Treasury on currency policy, while the Treasury has respected the Fed’s autonomy on issues such as short-term interest rates and demand stabilization. Scholars have explored the history of currency agreements and their coordinated implementation, highlighting their theoretical potential to address imbalances. However, the question remains: What incentive does the US have to pursue such agreements when it can unilaterally influence the terms of trade through the imposition of tariffs? The ability to dictate trade shifts without negotiation may diminish the appeal of entering cooperative currency arrangements, particularly when tariffs have already proven effective in exerting leverage.

A coordinated currency agreement would require careful negotiation to align the interests of major economic powers. The Treasury and Fed would need to strike a balance between stabilizing exchange rates and maintaining domestic economic goals, such as controlling inflation and promoting employment. Ensuring that currency policies align with broader trade objectives, including tariff adjustments, would further enhance economic stability while reducing global trade tensions.

Proposal for the Mar-a-Lago Agreement

A multilateral currency agreement, similar to the Plaza Accord, could contribute to economic stability under specific conditions. However, in the current geopolitical climate, achieving such an agreement is challenging. To gain cooperation from major reserve-holding countries like China and Middle Eastern nations, a different diplomatic approach would be required.

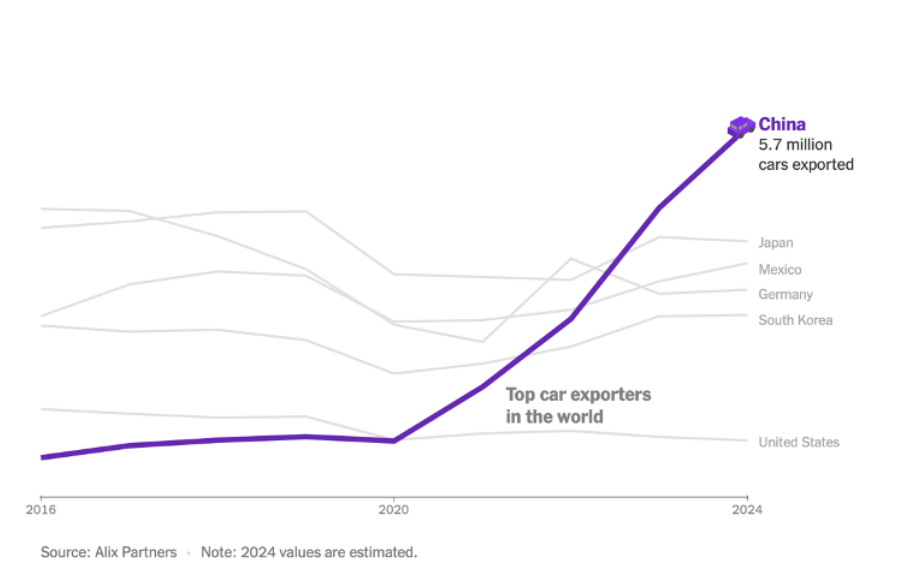

Globally, Europe and China show limited willingness to coordinate on currency policies. Europe faces sluggish growth, and protectionist measures dominate its response to Chinese export competition. Meanwhile, China’s weak domestic growth compels it to reinforce its export-driven model. Notably, China has emerged as the world’s largest car exporter, intensifying global trade tensions.

Top car exporters in the world. Via The New York Times.

China’s dominance in the global EV market is a result of strategic government support, economies of scale and advances in automation. These factors have enabled Chinese companies to produce EVs at competitive prices, making them attractive to global consumers. Simultaneously, with weak domestic demand, China’s excess capacity has been absorbed by export markets. The country’s EV exports have grown significantly, with Chinese brands like BYD gaining recognition worldwide. This trend is expected to continue, solidifying China’s position as a leader in the global EV market.

By contrast, nations like Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada and Mexico may be more open to cooperation but lack sufficient influence to drive global outcomes. The Trump administration’s strategy of using tariffs as leverage could potentially lead trade partners to agree to currency pacts in exchange for reduced tariffs.

A potential agreement, the “Mar-a-Lago Agreement,” might resemble historical precedents like the Plaza Accord but would require “harmony negotiation” in the spirit of a former Secretary of State and Treasury James Baker, rather than a blunt “carrot-and-stick approach,” given today’s complex financial landscape. This scenario differs significantly from the Plaza Accord era, as Japan’s trade relationship with the US then was largely centered on exporting finished goods. Currently, tariff policies also impact US manufacturers and retailers, highlighting underappreciated complementarities that are often overlooked in the present discourse.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment