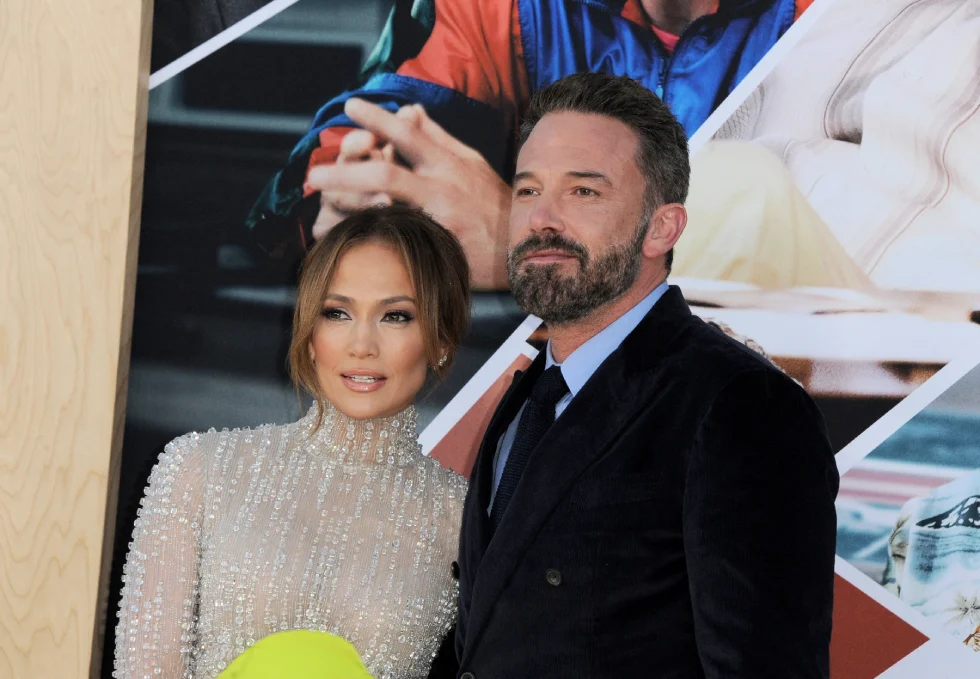

“Jennifer Lopez and new flame Ben Affleck kissed, cuddled and made goo-goo eyes at each other for hours yesterday as the Latina lovely was feted at a surprise birthday party.” So reported the New York Post on July 25, 2002. It was the first of countless stories about the couple known sometimes-affectionately as “Bennifer.”

Twenty-two years later, the news broke: Bennifer is over — again. In the interim, there had been an engagement, two marriages (to other people), five children, more than 18 new fragrance endorsements, a few box office bombs, several spells in rehab and an Oscar. And, for a while, the kind of media delirium that produces headlines like “BEN AND JEN: BODY LANGUAGE: WHAT IT MEANS,” “J.LO: ‘BEN DEFINITELY WEARS THE PANTS’” and “STRIPPER TELLS OF NIGHT WITH BEN.” Perhaps the most memorable was “BEN AND JEN SAY ‘NOT YET.’” In September 2003, Lopez visited her spiritual guide, spent two hours with her, then announced she was calling off her hugely publicized wedding with Ben Affleck. So the most recent breakup conjures a sense of déjà vu.

Here’s my question: Why? No, not why does this pair keep getting together, splitting up and then kissing-and-making-up before parting again? The more interesting question is: Why on earth are we so fascinated by them? For that matter, why are we fascinated by celebrity couples and their endless caprice?

Taylor-Burton: The beginning of celebrity couple coverage

Precedents can be found in the life of Elizabeth Taylor, whose combustible affair with Richard Burton imploded in 1974, after 12 years, only to regenerate itself in 1975. They married each other for the second time, but this marriage ended in less than a year. Taylor’s volatile romance is customarily considered the first modern celebrity coupling in the sense that it was copiously covered by the media. Because of this, it effectively promoted audience interest in how the other half love.

The Taylor-Burton amorous entanglement was a commodity — open, visible, public — compared to, for example, Ava Gardner’s erratic but essentially private romance with Frank Sinatra in the same period. With Gardner, the media were made to work for their stories.

Taylor, probably more than Burton, practically handed out press packs. Their relationship was a romance in the golden age of the American dream factory. As such, it was glitzy, glamorous and, at times, gaudy. There might have been some hesitance, perhaps even reluctance to stampede into Gardner’s and Sinatra’s private lives, especially as there were spouses and, more importantly, children to consider. Were the media likely to contribute to marital disharmony and even the sadness of innocent children merely by reporting the relationship? Taylor removed those kinds of uncertainties. She practically directed events, which involved double-home-destruction on a catastrophic scale.

Taylor, like Gardner, reminded the world that women could be and often were prime movers in relationships. Sinatra went on to become one of the preeminent entertainers of the 20th century. But during the marriage (1951-1957), Gardner, not he, was the main attraction. One inquisitive enquirer once asked her why she stayed with the 119-pound Sinatra. Gardner replied “Well, I’ll tell you — nineteen pounds is cock.”

Similarly, Taylor was the force field that pulled in media from all over the world. Being the consummate Hollywood star — Burton had learned his art on the stage — Taylor knew the value of ostentatiousness. She behaved as if she were always in front of a camera. She usually was.

Tabloids and the new voyeurism

There was nothing comparable until 1999, when Jennifer Aniston and Brad Pitt appeared together at the Emmys and announced a relationship that was, for all intents and purposes, conducted in front of cameras. This included a lavish Malibu wedding in July 2000. The marriage lasted until 2005, by which time J.Lo’s epic relationship with Affleck was known, had taken over as the celebrity coupling du jour and, in time, supplied a narrative of Homeric proportions.

There were other breakups that took the entertainment world by storm: Britney Spears and Kevin Federline separated in 2006. Justin Timberlake and Cameron Diaz broke up in 2007. But Lopez and Affleck was epochal: It characterized a period when the media’s interest in the unappetizing areas of celebrity life was rising and audiences gave their approval to the increased coverage. One way they did this was by buying tabloid magazines.

Sales of the likes of Us Weekly, People and Star have slipped in recent years as social media has become the main conduit of celebrity gossip. But their impact in the early 2000s was appreciable and played no small part in cultivating our near-voyeuristic interest in glamorous couples. It could be plausibly argued that there was little new in this. Some might maintain that audiences had long been attracted to dreadful experiences while they remained at safe distance. Living through awful times vicariously may have its rewards: Just imagining how others feel rather than actually feeling is a pain with its own analgesic properties.

The decision by Aniston and Pitt to split and Pitt’s subsequent romance with Angelina Jolie was the affair that shook tabloid journalism. It alerted editors that audiences enjoyed learning about how people who otherwise led charmed lives were just as susceptible to the same painful ordeals and privations as anybody else.

This is part of the reason for our prolonged captivation with Lopez and Affleck and, to a lesser extent, other celeb couples. We might envy their lifestyles and adulation. We might even engage in wish-fulfillment and imagine what the world must be like with an A-list partner. Yet, there is gratification in learning that even the world’s most fabulous couples experience mundane squabbles and domestic discord, reminding us that beneath the glamor, they too are just as human as we are.

Performative coupledom and authenticity

That’s not the only reason we’re drawn to celebrity couples. Harper’s Bazaar writer Marie-Claire Chappet uses the term “performative coupledom” to describe the way many couples like J.Lo and Affleck present themselves to the media for our delectation. Chappet argues that celebrity couples are not passive recipients: They pull out as many stops as they can to maximize the inquisitiveness of the media. Coupledom can be a valuable and highly commodifiable item.

Chappet also suggests there is a kind of synergy in performative coupling. “Just look at Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez,” she writes, “both huge stars whose wattage flickered all the brighter once they got back together. In fact, in many ways, this couple are the ultimate embodiment of this trend.” The colossal coverage given the latest breakup underlines her point.

Neither party swept gracefully upwards after the 2003 breakup. Affleck had scored a triumph with his Oscar-winning film Argo, but had featured in flops, too. He struggled with alcohol dependency and had at least three periods in rehab. Lopez’s career also seemed to spiral downwards when she appeared on the television series American Idol. But to her dubious credit, her Super Bowl halftime show appearance in 2020 elicited 1,312 complaints from viewers to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). She was 50 years old at the time and most of the complaints were about the sexual explicitness of her performance. The latest rift will surely regenerate interest in the ill-starred duo.

No celebrity couple is perfect. Even the best-matched partnerships hit unexpected and often hidden snags, obstacles that complicate or even destroy relationships. If a couple is seen as just too good to be true, the adage kicks in: It usually is. Celebrity couples must have the imprimatur of genuineness to captivate us. This means extremely short affairs, like Kim Kardashian’s 72-day marriage to Kris Humphries, are dismissed as stunts. Or, in the case of Britney Spears, whose marriage to Jason Alexander lasted 55 hours, they’re viewed as false-starts.

The seeming contradiction between an authentic relationship and performativity is smoothed over by audiences who like to see people at their best and worst. Today’s celebrity-savvy audiences suspect staging here and there and accept it. They are celebrities, after all. But couples must humanize themselves and remind audiences of their authenticity with everyday emotions, quarrels and fall-outs that serve to maintain captivation. An occasional rage helps, too.

J.Lo and Affleck may be waving goodbye to each other, but they might just as well be waving a banner bearing the slogan, “This is our pitch for immortality.” Individually, they’re probably worth a lot less than they are together. But even breaking-up unites them as far as the media and its audiences are concerned. The heartbroken pair appear to be marching toward celebrity immortality. Meanwhile, we wait for the reconciliation.

[Ellis Cashmore is the author of Celebrity Culture, now in its third edition.]

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment