Banaras is a lifetime of experience, delving into its innermost social fabric. This deep plunge may leave one intrigued and enthralled, longing for a rounded definition to what Banaras is and its archetypal Banarasipan. Interestingly, this insistent inquiry compelled me to address the corollary question of identity.

There is no ultimate definition to Banaras.

There are encounters, connections, and entanglements between the historical and the cultural, the social and the religious, and imagined antiquity, in Banaras. It is not about an age-old city, but perhaps, most intricately, about its people and their practices, which have stemmed, been shaped and reshaped across time, marked by what is real, literal, and what has been represented. To understand these ever-engaging intersections, as it forms a unique spatial and cultural identity for its citizens, is a complicated task for outsiders. For many, Banaras stands bare in its ceaseless chaos and confusion and yet it is undying and meditative, rather layered, and hard to decipher. It continues to be an anagram for me, much like its source faith system, Swayambhu (the mythology of Shiva in Banaras), that is believed to have emerged on its own, powerful and overwhelming. The purely religious point of view is the widely accepted lens to decode Banaras and its people, and to that, Banaras is well defined; it does not hold any definition beyond being “holy.” The imperative conclusion would be thus of the people living here full of piety and of being the vanguard of Hindu sacred practices. However, this understanding is not enough for me.

What would be more interesting is to deconstruct the enmeshed elements of the political and religious with the sociocultural narratives of what is Banaras, who is a Banarasi, what Banarasipan is, and how it has emerged.

It all begins with the unique question of whose city it is. As it is believed by millions, the city belongs to Shiva. Banaras or Kashi is his choice of earthly residence, a beautiful location that parallels no other. For eons of time, Shiva has resided in this city, since even before the city was embraced by the Ganges. Why would the Vedic god choose Banaras as his site of abode on earth? Why would he even leave his celestial home in the sacred mountains?—the questions are many. And the answers are imagined and prescribed, both rooted through the eulogy literatures, as well as in the folk narratives.

At the core of Shiva’s concept lies the notion of a free spirited, content, carefree wanderer, who even within the gambit of cosmic institutions (structure of heaven) is an itinerant at heart, always rebelling against the norms. He is jovial, broad-hearted, and can be interpreted as a “khula dil” personality—an essential characteristic associated to a typical Banarasi.

Shiva’s description is complex and awe-inspiring in the texts. He is real, believable, and liberating, much like what Banaras and its people are.

He wanders naked or clothed in the bloody skin of a slain elephant or tiger. When he leaves the Himalayas to dwell in the heart of culture, he makes his home in the cremation ground. He anoints his body with the ashes of the dead from the cremation pyre. He wears snakes about his neck for ornaments. He rides upon a bull and carries a trident as a weapon. He has no wealth, no family, no lineage, nothing of worldly value to recommend him.

Shiva thus challenges any facile distinctions between the sacred and the profane, the rich and the poor, high and low.

Essentially, the credibility in the notion of Shiva is reflected in the Banarasi way of life, a strange undefined happiness, contentment, large-hearted, fun-loving group of people, who welcome all visitors who make it to their city. This could even lead to a metaphorical interpretation of Banarasipan, where the sacred and the profane coexist in the same breath, where there is no rich and poor or high or low, for all would love to seek the worldly pleasures of enjoying the savouries and sweets—the rabris, thandais, kachoris, and gilohrees, enjoying days of spring in Holi or Ramleela in autumn.

This sense of fulfillment in the little joys of life, which is also often termed as “small traditions” by the scholars of South Asian studies, cuts across boundaries of faith and class in Banaras. There is a profound connect that every Banarasi feels towards their city. From the chaiwallah on the ghats, to the old retired wrestler, to the third generation snack maker, to master Banarasi craftsmen, to the youngest assistant of the undertaker, to the veteran Sanskrit scholar, to the learner of Hindustani classical music, and the common man on the road, Banaras is conceived, cherished, and lived in the same way. A regular conversation is never steered by caste, religion, or ethnicity; the bigger identity of being a citizen of Banaras emerges first and foremost. Everyone residing in Banaras is a Banarasi. In death too, there is not much stratification among the rich or the poor, other than the differences in last rites.

And however sentimental it may read, the Ganges too belongs to all. Essentially, it acts as a leveller erasing the minutest of differences in the city’s complex social fabric. The river is revered and loved by all. A secular Kabir refers to the Ganges; a Brahmin scholar, Tulsi Das Goswami, creates his devotional book, Ramcharitmanas, on the riverfront; a repentant poet, Jagannatha Panditaraja, surrenders to the Ganges; a man of letters, Bharatendu Harishchandra, writes his novels on its banks. Much later, the famed exponent of Kathak, Sitara Devi, would swim across the Ganges; the maestro of shehnai, Bismillah Khan, would practice for hours on the ghats only. The urban lore says that Khan never left Banaras, citing the absence of the Ganges in any other city.

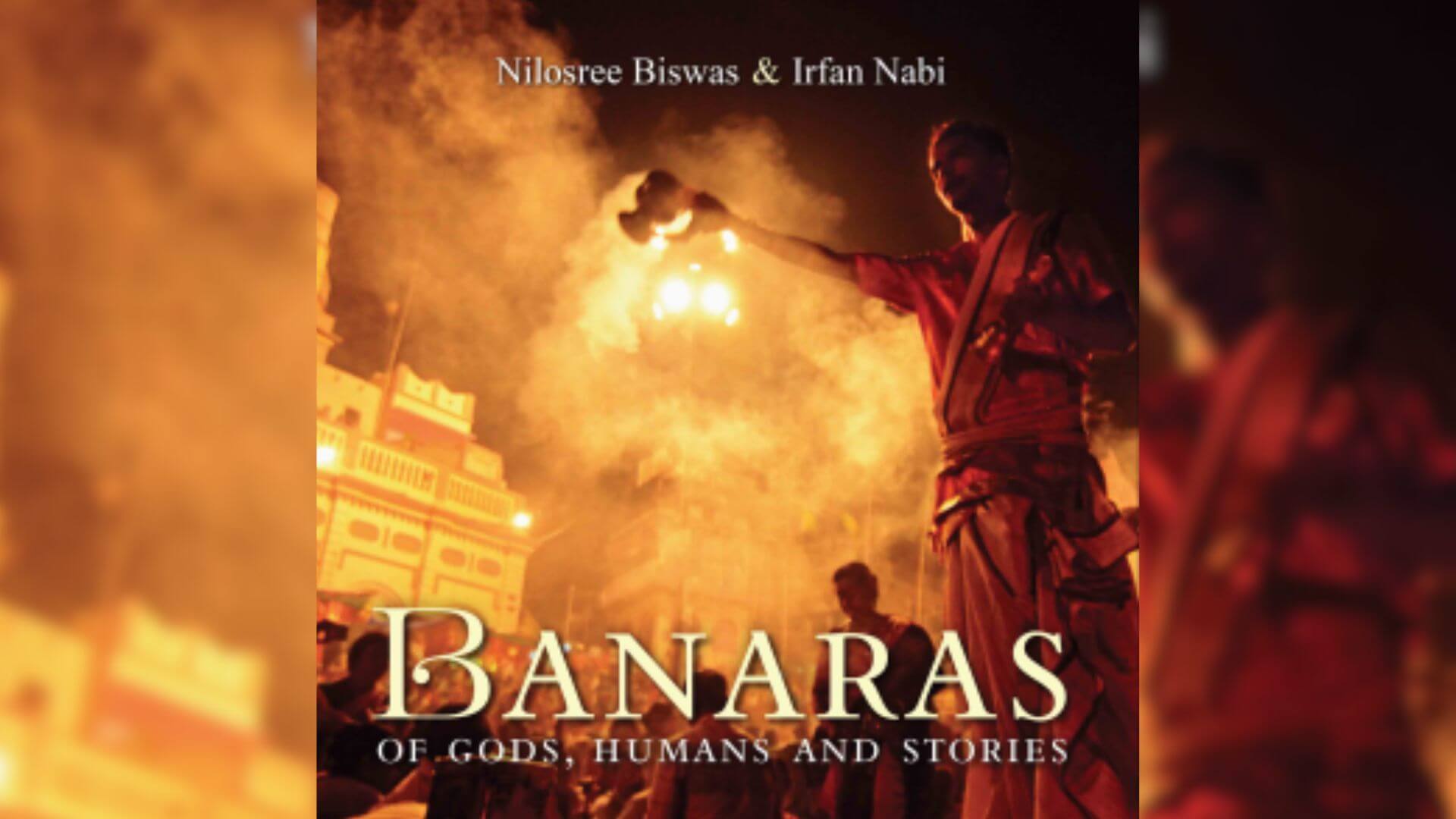

[Niyogi Books has given Fair Observer permission to publish this excerpt from Banaras: Of Gods, Humans and Stories, Nilosree Biswas and Irfan Nabi, Niyogi Books, 2021.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment