Overall, the world is at serious risk of demographic non-replacement. According to recent UN Population Division data, the global average birth rate is 2.3. This average, however, masks a severe problem. Globally, the countries still above 2.0 children per woman are those in Sub-Saharan Africa, some in Asia and very few in Latin America. On the other hand, Europe, Russia, Australia, Japan and North America, including Mexico, are below 2.0. This means the 15 largest economies in the world have a birth rate below the replacement rate, with a ratio of 0.8 children under 15 for every person over 65. Today, people aged 65 and over represent 20% of the global population. In 30 years, that number will double, from 700 million to 1.6 billion people.

These demographic changes have profound implications for the labor market. Those unfamiliar with it often think of the market as something abstract, but we forget that the market is made by and embedded in society and thus influenced by political and social factors. An analysis of the business environment is expected to focus on economic factors: GDP, unemployment, balance of payments, exchange rate and inflation; social and political factors are wrongly left in the background.

For example, some societies are more productive than others. The reason is multifactorial; however, that answer cannot be merely economic because productivity is not only a function of available resources and their proper allocation. The productivity of an economy also depends on political and social factors; among these, it is essential to mention the customs and habits of a society, the work culture and the formal and informal rules that shape a given social environment.

Demographics are the most overlooked factor for understanding productivity, innovation and the direction of economies in the coming decades. What is the relationship between aging demographic trends and productivity and innovation in the context of the fourth industrial revolution? This is the central question of this article.

The dominance of 65+: the beginning of the silver economy

The labor force participation rate (among those aged 20–64) will decline in most member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), as well as Russia and China among non-OECD countries, in the coming years. By 2060, the number of dependents per 100 working-age people will increase from around 1:20 in 1980 to 1:58.

This trend will have the most acute effects in countries like Japan, Finland and Italy (the three aging the most), while other countries with accelerated aging will follow close behind. These countries include Greece, South Korea, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Brazil, China and Saudi Arabia.

The “demographic dividend,” broadly understood as the economic benefits of a demographic pyramid where the share of the working age population is much larger than the dependent population, is now ending. Baby Boomers are retiring. The benefits of the demographic dividend, such as high demand for goods and services, low interest rates, cheap labor and abundant liquidity for savings funds, are fading. When societies age, governments face unsustainable social and healthcare expenditures, and companies lose innovation and productivity.

Japan: a laboratory of the future to come

As previously mentioned, Japan is among the three oldest populations in the world: 30% of its citizens are already over 65 years old. According to projections, its labor market will lose eight million workers in the next six years. In 20 years, it will go from 67 to 52 million people working — in a country of more than 130 million inhabitants. By 2060, its population pyramid will look more like an obelisk. This is already evident as unemployment in Japan is at its lowest point in 26 years, with 1.5 job vacancies for every applicant.

The government recognizes that the country is aging and losing strength. However, the national development strategies seek to return to 4% productivity and growth above 3%. Japan aims to achieve this by relying more on advanced technologies, shoring up labor discipline and productivity, and adopting global best practices.

There are many exciting new technologies and practices in Japan that offer tailor-made solutions to the growing segment of the 65+ population. Curves International, Kozo SNS Village and Club Tourism offer leisure activities and travel packages that take into account the specific needs and interests of the “platinum segment.” Companies such as 7-once and Benry Convenience Services specialize in food delivery, home maintenance and daily errands. While these kind of solutions are valuable to society at large, they are particularly meaningful in case of the 65-and-older. Going out to do shopping, walking your dog or even taking the trash out may be a challenge for some elderly people. Whill Corporation provides short-distance automobility solutions. Whereas there are plenty of medium to long-distance shared mobility services to get to the airport, to the doctor or to your office, there are very limited transportation options when it comes to buying groceries in your convenience store “just behind the corner”. Whill’s solutions allow people to remain mobile, active and independent within a few miles around home. Mysteryminds offers inter-company mobility services, which become especially important when talent is scarce and there is a clear need to build highly flexible multi-generational teams that pool together different skills and experience.

If one sector in particular is changing dramatically, it is undoubtedly the health sector. Medical care is expensive, and hospital stays are often three times longer in Japan than the US average. Hospital treatments are not sustainable for either public or private spending, especially with chronic conditions. Increased robotization and automation of various tasks are necessary to meet the demand. Humanoid robots are being employed in remote patient management, assisting with self-medication and automating administrative support. The average nurse in a nursing home can take up to 90 seconds to move an older adult. With a robot to help stabilize hip issues and provide leverage, this goes from 90 to 40 seconds. In an aging society, the difference of 50 seconds adds up quickly.

Not having “healthy” demographics is a severe structural problem for the future of any country. Because the classic options such as pro-family, pro-equality and pro-immigration policies have not yielded significant results, Japan has moved from denial to correction, mitigation and adaptation. In the near future, the government will use technology to remain among the most advanced economies even with an inverted demographic pyramid.

Technology advances v social customs: an ongoing battle

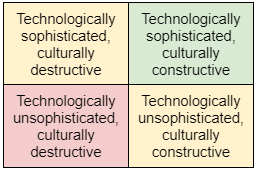

The case of Japan provides an insight into the relationship between society and technology, which can be both positive and negative. One way of looking at this relationship is a two-axis matrix. On the vertical axis is technological sophistication, and on the horizontal axis are the types of social uses and customs, from upbeat and creative to harmful and destructive. This combination gives us four quadrants.

Of course, it is not in any society’s interest to be in the quadrant with the double negative: low technological advances and, at the same time, destructive habits and customs. In the adjacent quadrants, there is a lack of alignment between the degree of technological advancement and the prevailing customs and practices, which prevents progress. For many countries, the challenge is that a lot of technology that could lead to more productivity is available, and yet society may reject those technological advances for fear of losing relative social status and acquired legal privileges.

What society wants may be very different from what the public sector sees as a national priority. The case of Japan is relevant here. On the one hand, there is the national agenda: Japan wants to remain among the seven most advanced economies in the world. On the other hand, there are the priorities and personal expectations of millions of people who want to retire, or work less which conflicts with that national agenda.

Because of this, Japan is a social experiment reshaping the society–technology relationship as a means of satisfying both sides. However, these complex issues such as the broader social contract in terms of public policy and social obligations will not be so easily solved. The public sector is facing the sociocultural limits of necessary reforms regarding gender parity, immigration and social diversity and pro-family policies. This is why other sectors, especially business, should be involved in mitigating the impacts of rapid aging and adopting the economy to a new social reality.

Lessons for the world

The social experiment conducted in Japan is a cautionary tale future economies should try to avoid. Although Japan seems to have the resources, know-how and political will to make the combination of aged society and advanced technologies work, the risks of failure are high. Advanced technologies are not an easy substitute for structural reforms. In an aging population, the state will probably have to privatize more and invite more foreign direct investment to have economic growth and maintain state revenues.

The silver economy will certainly have many new opportunities in terms of products and services. But in an aging society, there will be a risk of lower actual returns for investors because they have a smaller economy, less growth and fewer young people (who are more disruptive). That lack of dynamism can lead to capital outflows, lower dividends and financial crises.

The next decade or so will tell us whether technology will help Japan cope successfully with an aging population.

[Beaudry Young edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment