This is the first in a series of musings about the inter-relatedness of the ego, awareness, sense of self, cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Science is trying to solve the deepest mysteries and Benoit Wolff and Vaughn Gray bring us the latest on this.

It is in the center of our lives and yet fairly unknown: our self. At least from a scientific standpoint, the self remains a mystery that has lead to a never-ending scientific debate and countless pages of theory. Disciplines like philosophy, psychology, psychoanalysis and the neurosciences, to name only a few, have come up with a plethora of possible explanations concerning its nature and functioning.

Philosophy

On the philosophical scene, the self became prominent with René Descartes’ Discourse on Method (1637), which brought the dawn of modern, subject-centered rationalism. It introduced an unprecedented figure to Western thinking: the ego, an entity conceived as purely rational, yet not necessarily corporeal: “I think, therefore I am.” There’s ‘something’ doing the thinking; hence its existence, in a very broad sense, cannot be doubted, like that of one’s hair or colour of the eye. In the Frenchman’s reasoning, these properties could after all be a neat illusion caused by an ‘evil spirit’. David Hume (1711-1776), a Scottish empiricist, offered a radically conflicting concept of the self. According to Hume, sensory perception, not reason, is the connection between an individual and reality. With every sensory impression, a new world emerges. Consequently, the self, a part of that world, is not a single, uniform entity, but a bundle of multiple impressions brought about by our sensory apparatus; a fragmented thing lacking identity. From the Enlightenment on, German thinkers such as Kant and Fichte rehabilitated the self (“Ich”) by making it the absolute principle of thinking and, subsequently, understanding.

Psychology

With psychology’s rise as an academic and empirically scientific discipline throughout the 19th century, the self was soon tackled from other angles, with different approaches leading to new insights and theories. In Germany, Wilhelm Wundt (a physiologist and philosopher) and Gustav T. Fechner (a physicist) founded the Institute for Experimental Psychology; in the US, William James, the father of American psychology, drew extensively on the work of Wundt and Hume amongst others, the former of which was the author of numerous papers on the theory of sensory perception. Examining the theories of his German fellows, James himself aimed to provide a description of the self that differentiated between a “pure ego“ or “self as knower” (“I”) and an “empirical ego” or “self as known” (“Me”). He did not, however, leave it at this simple dichotomy, but further specified the known self, claiming that it is a complex compound with material, social and spiritual shares. Body, material goods, roles played in society, morals, beliefs – all of these, according to James, make up the self-knowledge each and everyone has.

Towards its end, the same century brought about a revolutionary explanatory model for the human psyche: psychoanalysis, as founded by the neurologist Sigmund Freud. It includes a structural theory of the ego, explained in the light of the unconscious and libidinal id (realm of the basic drives) and the equally unconscious, but criticizing and guiding superego (a sort of conscience). The conscious ego, ‘caught between’ two unconscious and antagonistic psychic poles and exposed to the id’s aggressive drives as well as the superego’s rules and bans, constantly struggles to maintain the balance between the two other forces. Basically, Freud viewed the ego as a mainly passive sense organ that relates to the outside world through perceiving and responding to external (as well as internal) stimuli. Only later did he grant the ego active power because it can control the id’s impulses.

Resuming Freud’s doctrine, several psychoanalysts, among others Freud’s daughter Anna Freud and the Americans René Spitz and Erik Erikson, developed ‘Ego psychology’, an independent branch of psychoanalysis dedicated exclusively to the exploration of the ego, its normal and pathological development, and its adaptation to reality. They greatly emphasized early-childhood experiences (Spitz), a factor considered relevant for understanding the ego’s complex nature. Also, Freud’s largely psychosexual model of the ego’s phases (such as oral, anal, oedipal, to name a few) was broadened by a psychosocial dimension (Erikson), taking into account socio-cultural influences that play a crucial role in the ‘shaping’ of the self.

Neurosciences

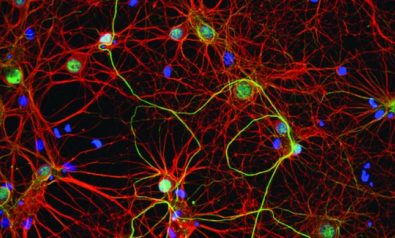

Neurosciences are relatively new in the field of ego research. The term refers to a large group of disciplines that investigate the structure and functioning of the nervous system. Brain research (with origins dating back to ancient Egypt 3500 BC) has lately achieved considerable success in ‘watching’ and localizing the process of decision making associated with the exertion of free will. This feat has largely been made possible by new screening techniques such as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imagining) which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s and has provided unprecedented insights into activities of the human brain. Speaking of which, consciousness is yet another area on which research is carried out intensively. ‘Neuronal correlates of consciousness’ (brain activities that correspond to conscious processes) are a main interest. So far, only very basic cognitive functions, like the perception of forms, can be related to brain areas successfully, and yet the method may one day link more complex functions like thinking – including thinking about oneself – to certain parts of the brain, thus maybe ‘materializing’ the ego. Brain research and neurosciences are an important counterbalance to the purely hypothetical and theoretical constructs of psychoanalysis and philosophy. The newer disciplines may decide on the credibility of those previous theories.

Beyond philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience, spiritual thinkers in the east and west have been interested in the idea of the ego for millennia. The central teachings of Buddhism revolve around the idea of a false self, which each of us believes is who we are. This false self is seen as the source of dysfunction and unhappiness in our lives and the spiritual practices of Buddhism are aimed at freeing our minds from our own false self. Ancient Hindu writings also allude to the idea of a false self – an identity we believe to be the essence of who we are but which is not who we really are. One way of understanding this is to consider the idea that our essence – our real reality – is our consciousness. Our ‘self’ (or ego) exists within our consciousness but is not a part of it. The ego is an object of consciousness, whereas the subject is consciousness itself – who we really are. The ego is simply something we perceive through our consciousness and is no more who we are than a table we see, a breeze we feel on our skin, or a song we hear. The only difference between our ego and a song we hear is that the ego is a thought experience in consciousness which contains the thought “this is really me“, whereas a song we hear is a sensory experience in consciousness with no message of selfhood contained therein.

In recent years scientists have begun to investigate the way spiritual practices change brain activity. Perhaps the day is not far off when scientists, philosophers, psychologists, and spiritual thinkers will arrive together at a single unequivocal conception of the self, and it will be clear that all had been moving towards the same truth all along.

Our Goal at Fair Observer

Together with Samuel Weber, a leading American thinker across the disciplines of philosophy and psychoanalysis at Northwestern University, we want to make sense of the ego from a Freudian perspective and tackle issues such as self-consciousness and the paradoxical ‘conscious unconscious’.

After this dip into the human psyche, Vaughn T. Gray, an American wellness entrepreneur with an MA in Human Sciences from Oxford University, will explore a broader concept of self-consciousness embracing sense perception and the idea of a self beyond the purely conceptual ego.

Disorders of the self, such as multiple personality, schizophrenia, and dementia will be explained by Elmar Kaiser, a German MD and specialist for psychiatry and psychotherapy at the university hospital in Heidelberg.

Benjamin Maier, an aspiring cognitive neuropsychologist with a BA in psychology from San Diego State University now studying at the LMU in Munich, will dig deep into the neuroscientific field. He will examine self-referential thought and brain areas that play a crucial role in processing information related to the self, thus investigating the cerebral realm of the self.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.