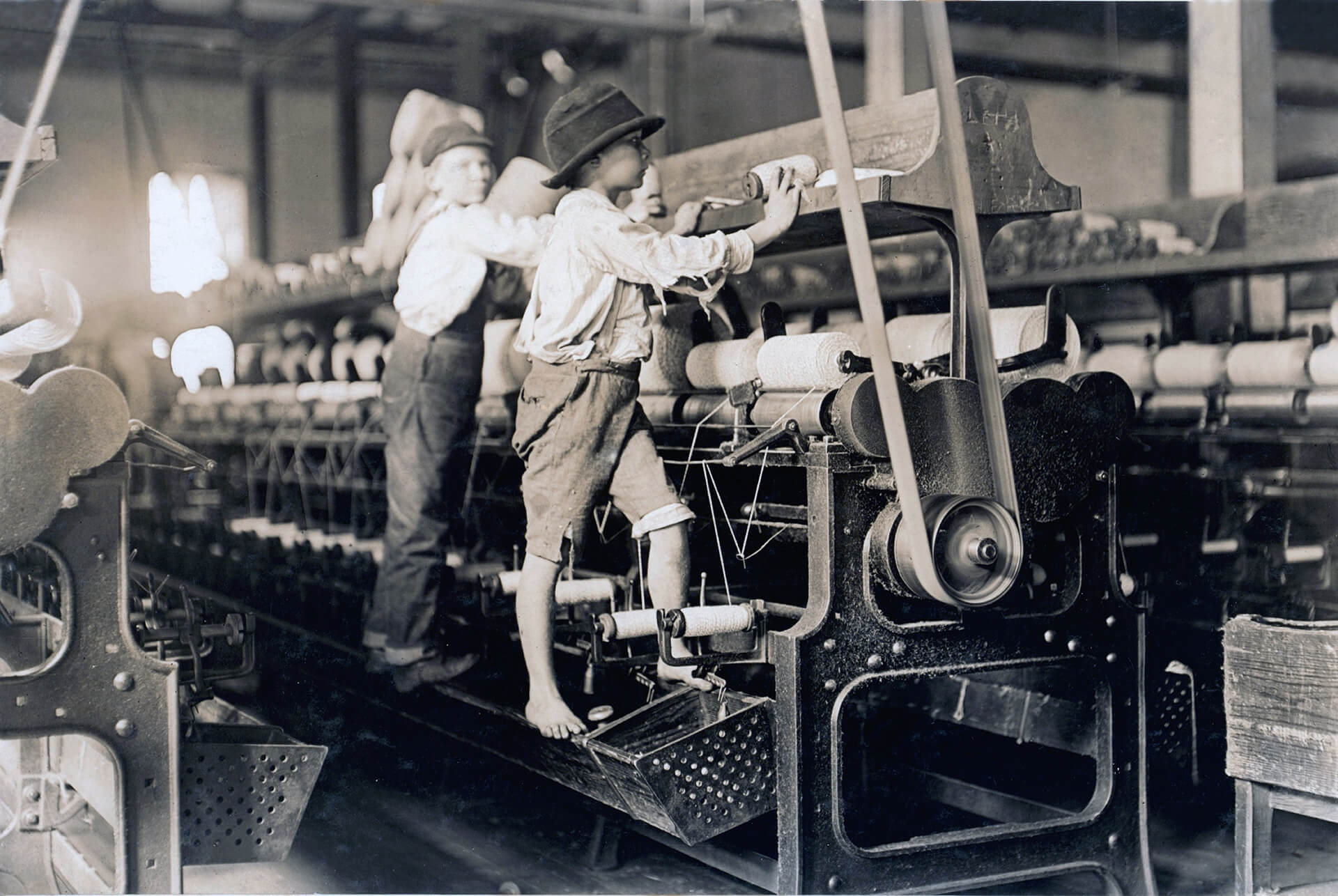

An aged Native American chieftain was visiting New York City for the first time in 1906. He was curious about the city, and the city was curious about him. A magazine reporter asked the chief what most surprised him in his travels around town. “Little children working,” the visitor replied.

Child labor might have shocked an outsider, but it was all too commonplace then across urban, industrial America, as well as on farms, where it had been customary for centuries. Well into the twentieth century, industrial capitalism depended on the exploitation of children who were cheaper to employ, less able to resist, and until the advent of more sophisticated technologies, were well suited to deal with the relatively simple machinery then in place.

In more recent times, however, it became a far rarer sight. The Progressive movement and the labor unions combatted child labor until President Roosevelt made “oppressive child labor” illegal with the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The practice has since come to be seen as something repulsive. Law and custom, most of us assume, drove it to near extinction. Our reaction, if we were to see it reappear, might resemble that chief’s: shock and disbelief.

You might be in for a rude awakening: Child labor is making a comeback with a vengeance. A striking number of lawmakers are making concerted efforts to weaken or repeal statutes that have long prevented, or at least seriously inhibited, the possibility of exploiting children.

A nationwide campaign for child labor

Take a breath and consider this: The number of kids at work in the US increased by 37% between 2015 and 2022. During the last two years, 14 states have either introduced or enacted legislation that rolled back regulations governing the number of hours children can be employed, lowered the restrictions on dangerous work or legalized subminimum wages for youths.

Iowa now allows those as young as 14 to work in industrial laundries. At age 16, they can take jobs in roofing, construction, excavation and demolition and can operate power-driven machinery. Fourteen-year-olds can now even work night shifts, and once they hit 15 can join assembly lines. All of this, of course, was prohibited not so long ago.

In 2014, the Cato Institute, a right-wing think tank, published “A Case Against Child Labor Prohibitions,” arguing that such laws stifled opportunity for poor — and especially black — children.

The Foundation for Government Accountability, a think tank funded by a range of wealthy conservative donors including the DeVos family, has spearheaded efforts to weaken child labor laws. Americans for Prosperity, the billionaire Koch brothers’ foundation, has joined in.

Nor are these new laws confined to red states like Iowa or the South. California, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota and New Hampshire, as well as Georgia and Ohio, have been targeted, too. Even New Jersey passed a law in the pandemic years temporarily raising the permissible work hours for 16- to 18-year-olds.

Legislators offer fatuous justifications for such infringements of long-settled practice. Working, they tell us, will get kids off their computers or video games or away from the TV. Or it will strip the government of the power to dictate what children can and can’t do, leaving parents in control — a claim already transformed into fantasy by efforts to strip away protective legislation and permit 14-year-old kids to work without formal parental permission.

Children work throughout the economy

At this point, virtually the entire economy is open to child labor. Garment factories and auto parts manufacturers like those that supply Ford and General Motors employ immigrant kids, some for 12-hour days. Many are compelled to drop out of school just to keep up. In a similar fashion, Hyundai and Kia supply chains depend on children working in Alabama.

It’s an open secret that fast food chains have employed underage kids for years and simply treat the occasional fines for doing so as part of the cost of doing business. Children as young as 10 have been toiling away in pit stops in Kentucky, and older children have been working beyond the hourly limits prescribed by law. Roofers in Florida and Tennessee can now be as young as 12.

In Vermont, “illegals” (called this because they’re too young to work) operate milking machines. Children help make J. Crew shirts in Los Angeles, bake rolls for Walmart and produce Fruit of the Loom socks. Danger lurks.

Recently, the Labor Department found more than 100 children between the ages of 13 and 17 working in meatpacking plants and slaughterhouses in Minnesota and Nebraska. And those were anything but fly-by-night operations. Companies such as Tyson Foods and Packer Sanitation Services (owned by Blackstone, the private equity firm) were also on the list.

As the New York Times, helping break the story of the new child labor market, reported last February, underage kids, especially migrants, are working in cereal-packing plants and food-processing factories.

Journalist Hannah Dreier has called it “a new economy of exploitation,” especially when it comes to migrant children. A Grand Rapids, Michigan, schoolteacher, observing the same predicament, remarked: “You’re taking children from another country and putting them almost in industrial servitude.”

Child labor is a sign of a system in moral decline

American capitalism is a global system, and its networks extend virtually everywhere. Today, there are an estimated 152 million children at work worldwide. Not all of them, of course, are employed directly or even indirectly by US firms. But they should certainly be a reminder of how deeply retrogressive capitalism has once again become both here at home and elsewhere across the planet. We have turned back the clock by over eighty years.

Boasts about the power and wealth of the American economy are part of our belief system and elite rhetoric. However, life expectancy in the US, a basic measure of social progression (or retrogression), has been relentlessly declining for years. Health care is not only unaffordable for millions, but its quality has become second-rate at best — if you don’t belong to the top 1%. In a similar fashion, the country’s infrastructure has long been in decline, thanks to both its age and decades of neglect.

Think of the United States, then, as a “developed” country now in the throes of underdevelopment. In that context, the return of child labor is deeply symptomatic. Even before the Great Recession that followed the financial implosion of 2008, standards of living had been falling, especially for millions of working people laid low by a decades-long tsunami of de-industrialization.

That recession, which officially lasted until 2011, only further exacerbated the situation. It put added pressure on labor costs, while work became increasingly precarious, ever more stripped of benefits, and de-unionized. Given the circumstances, why not turn to yet another source of cheap labor — children?

The most vulnerable among them come from abroad, migrants from the Global South escaping failing economies often traceable to American economic exploitation and domination. If this country is now experiencing a border crisis — and it is — its origins lie on this side of the border.

In addition, the Covid pandemic of 2020–2022 created a brief labor shortage, which became a pretext for putting kids back to work (even if the return of child labor actually predated the outbreak). Consider such child workers in the twenty-first century as a distinct sign of social pathology. The United States may still bully parts of the world while endlessly showing off its military might. At home, however, it is sick.

[TomDispatch first published this piece.]

[Erica Beinlich edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment