Politics changed forever 27 years ago. No election, assassination or international summit marked the shift. No tanks rolled, no walls fell. Yet a transformation occurred, not in America’s laws or institutions, but in how power was experienced, watched and consumed. Politics shed its sacred aura, became disconcertingly familiar and began to feel unmistakably like the kind of entertainment we were used to watching on television.

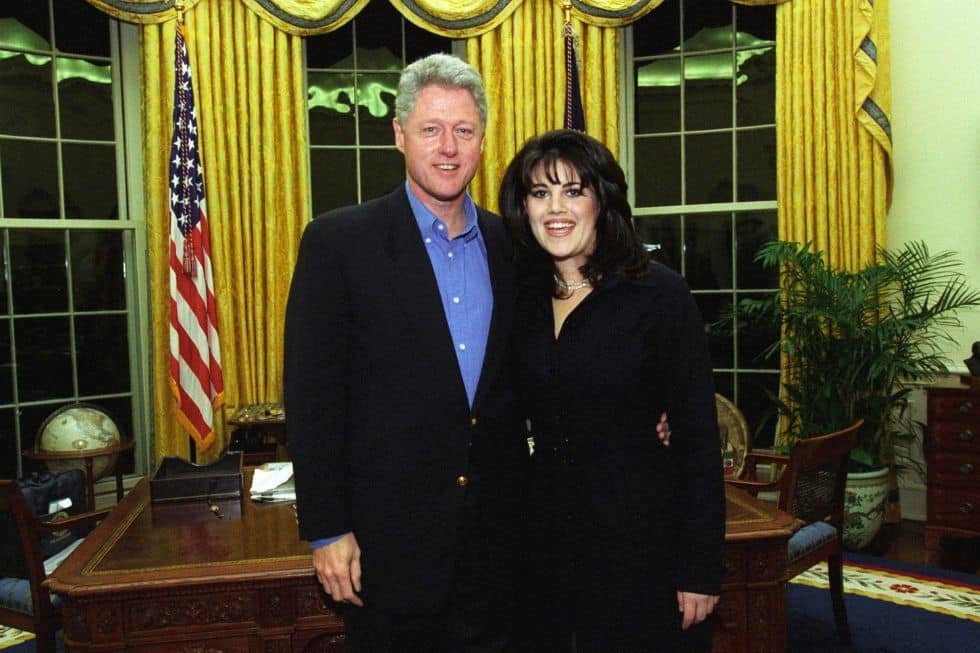

On August 17, 1998, after months of denials, US President Bill Clinton admitted to a grand jury: “I did have a relationship with Ms. [Monica] Lewinsky that was not appropriate. In fact, it was wrong.”

Sex scandals in American politics were certainly nothing new. President John F. Kennedy’s affairs remained whispered rumors, never televised. Gary Hart, daring reporters to follow him, sank like a stone when they did. Even Clinton himself had navigated earlier allegations from women, namely Gennifer Flowers and Paula Jones, that might have ended another politician’s career. But Monica Lewinsky was a different proposition. She wasn’t merely another woman; she was the central, unwitting protagonist in an international psychodrama.

What set her affair with Clinton apart wasn’t the sex, juicy as that was. It was the unprecedented, raw access: the leaked transcripts, the damning voicemail, the infamous navy blue dress. This wasn’t just a scandal; it was a high-definition spectacle, delivered directly to every household and in real time.

Accidental celebrity

Clinton made history by becoming the first sitting president to testify before a grand jury as the target of a criminal investigation. The questions were deeply personal and, at times, vulgar; the setting borderline surreal. Beamed from the White House via closed-circuit TV, Clinton answered prosecutors’ questions with lawyerly evasion and painstaking, almost excruciating, phrasing.

In one memorable exchange, the prosecutor asked: “Mr. President, do you understand that the statement that there ‘is’ no sexual relationship, an improper sexual relationship, or any other kind of improper relationship, could be false if indeed there was one, even though it’s in the past?” Clinton’s convoluted response became an instant cultural touchstone: “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is. If the—if he—if ‘is’ means is and never has been, that is not—that is one thing. If it means there is none, that was a completely true statement.”

Following his grand jury appearance, Clinton delivered a televised address to the nation. It was short, stiff and heavy with legalisms. He admitted the relationship had been “not appropriate” and that he had misled people, including even [his] wife.” He appeared unsettled yet spoke with an underlying defiance. The nation and indeed the world remained transfixed, unsure how to feel — disgusted, tantalized or simply impressed by Clinton’s audacious bravado.

Three days later, on August 20, American cruise missiles struck targets in Sudan and Afghanistan. Officially a response to the East Africa embassy bombings, Operation Infinite Reach was immediately dubbed a distraction. Jokes were made comparing these events to the previous year’s comedy film, Wag the Dog; in the film, a government spin doctor (Robert De Niro) and a Hollywood producer (Dustin Hoffman) work to fabricate a war in Albania to distract the public from a presidential sex scandal. It was, perhaps, the first time in history a significant international military action found itself relegated to a mere footnote in a domestic sex scandal.

What held this entire spectacle together, making it so utterly compelling, was Clinton himself. He wasn’t imposing like President Ronald Reagan, patrician like President George H.W. Bush or saintly like President Jimmy Carter. Clinton was fundamentally different. He possessed the easy manner of a man you might chat with in a Walmart supermarket checkout line — someone seemingly knowable, perhaps even someone who might flirt with you. His flaws, his all-too-human messiness, ironically, made him the first truly relatable president. That quality, once unthinkable in a commander-in-chief, now became an unexpected asset.

The age of the spectacle

By the end of that August, America’s political culture had undergone a quiet yet profound and lasting transformation. The presidency, once associated with distance and solemn dignity, had become a pivotal component in the nation’s entertainment machinery.

By the late 1990s, America was already a nation expertly “trained in watching.” Talk shows routinely blurred the line between confession and performance. Paparazzi relentlessly pursued not just film stars, but increasingly, reality TV personalities. Shows like Jerry Springer packaged dysfunctional families as primetime entertainment. Stores now offered more than groceries — they stocked America’s new unholy secular scriptures: glossy weekly gossip magazines like People and National Enquirer. Into this readied landscape stepped Lewinsky: intern, lover, national punchline and, ultimately, a reluctant protagonist in the most-watched real-life soap opera the world had ever seen.

But to grasp how Monica became Monica™ — a name that, for a time, needed no surname — we need a brief glance at the preceding cultural landscape. Few figures shaped that terrain more dramatically than Madonna. Throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, the diva transcended mere pop stardom; she was a cultural agent provocateur who taught audiences how to look, how to stare and, crucially, how not to look away.

She turned taboo into a trending topic years before hashtags even existed. Whether simulating masturbation on stage, publishing her explicit 1992 book, Sex or using the word “fuck” repeatedly on the Late Show with David Letterman, Madonna didn’t just push boundaries — she dissolved them. More significantly, she made it respectable, even desirable, to gaze intently… and to enjoy the spectacle.

By the time Clinton’s affair was exposed, the public was ready. What once might have been muttered discreetly became common watercooler chat. And the media, by then no longer deferential gatekeepers but increasingly predatory content chasers, knew how to satisfy the appetite for tittle-tattle. Monica™ was like a gift from heaven.

Clinton’s scandal wasn’t merely covered; it was serialized. It possessed a clear structure, escalating suspense, compelling secondary characters (like civil servant Linda Tripp and attorney Ken Starr) and even unexpected wardrobe plot points. Lewinsky’s semen-stained blue Gap dress transcended mere evidence, as did a cigar Clinton used as a sex aid. They became pervasive cultural references, almost sacred objects in a new age of scandal. The narrative had sex, power, concealment, betrayal and a president who, with every denial, seemed only to get more intriguing.

In an earlier era, shameful exposure meant indelible disgrace, dishonor and often everlasting stigma. But shame was in the process of being redefined. It might still have felt temporarily humiliating, but it carried no lasting loss of respect or esteem and the disgrace was far from indelible: It was quickly effaced. But, with the rapid ascendance of celebrity culture, shame seemed oddly out of place. Becoming famous by any means necessary was quickly becoming a legitimate career aspiration and shame, at times, was simply accepted as collateral damage.

Lewinsky became an accidental celebrity: a woman who, by her own later admission, lost not just her privacy but her “reputation and dignity and … almost [her] life.” Clinton, meanwhile, seemed to waft above it all, protected less by institutional power than by his sheer attractiveness, an undeniable charisma and an audience seemingly too rewarded by his very human antics to abandon him.

It’s easy to categorize the scandal as purely political, and of course, it did have political consequences. But at its heart, it belonged less to Washington, DC, than to global popular culture. The public wasn’t shocked by what Clinton did; it was utterly captivated by the unprecedented access. People were allowed to watch it all unfold. The real revelation wasn’t about morality; it was about media. The affair didn’t signal the fall of a president; it heralded the rise of the culture of spectacle.

Scandal fatigue

“If you can’t trust the president to tell the truth, who can you trust?” an incredulous reporter asked. But for much of the public, that question entirely missed the point. By then, Clinton was no longer being measured by old-fashioned virtues like trustworthiness or reliability, but by his performance.

Remarkably (perhaps), his approval ratings spiked after he admitted to the Lewinsky affair. This wasn’t despite the scandal: it was, in a perverse way, because of it. His transgression became fused with his relatability, even his disarming authenticity. The public was so exhausted by the continual prurient allegations against the president that what might have started as shock or indignation became an agreeable distraction. “Scandal fatigue” was the term used to describe the cultural desensitization.

He lied, he squirmed, he strangled grammar (as demonstrated previously when he defined the word “is”). But he did it all in plain sight. For a public raised on The Oprah Winfrey Show, The Geraldo Rivera Show and the confessional stylings of reality TV, that transparency almost felt honest. (Today, of course, we are all habituated to US presidents who lie, squirm and strangle grammar.)

Lewinsky, meanwhile, was publicly and savagely destroyed. “I was patient zero of losing a personal reputation on a global scale,” she reflected years later, keenly aware of the Internet’s embryonic yet devastating role in her humiliation. Her name became a cipher for shame, a global punchline in a thousand late-night monologues. Yet, in time, she courageously reclaimed her voice, emerging not as an object of scandal but as a speaker, writer and advocate against cyberbullying. If Clinton represented the survival of political power through personal disgrace, Lewinsky came to represent something arguably more modern and profound: the possibility of a woman surviving a potentially ruinous global scandal and, in the process, discovering agency.

The end of privacy

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of August 1998 wasn’t political or purely personal. It was cultural: the irrevocable departure of the concept of a “private life” for public figures and, eventually, for virtually everyone. Clinton’s affair and the ravenous media machinery it cranked into life were features of a nascent era in which visibility became permanent, intimacy became endlessly shareable and secrets became monetizable. And everyone was left asking and answering a question: If the most powerful man in the world couldn’t conceal an affair, who the hell could?

Fast-forward to July 2025. At a concert performed by rock group Coldplay in Foxborough, Massachusetts, the jumbotron’s kiss-cam pans to a couple sharing what appears to be an intimate moment. The image flashes on massive screens across the stadium. The woman recoils, visibly embarrassed, as she realizes she’s been caught on camera. Coldplay frontman Chris Martin even comments on the scene. Within hours, the video of the brief encounter goes viral across social media. Reddit threads speculate wildly about a potential affair as TikTokers frantically try to identify the pair. X explodes with memes. No one, anywhere, pauses to ask if this exposure was fair or proper. The story wasn’t about morality.

That fleeting moment, brief yet dramatic and seemingly random, is connected to August 1998 by a kind of molecular chain. It serves as a gentle reminder that the rules, such as they were, have fundamentally changed. There is no on-stage versus off-stage anymore. No quiet corner of life remains immune to broadcasting. There is no longer true privacy. We are all potentially “that woman” or “that man” now — framed, packaged and offered for the casual delectation of anyone. We are all shareable now. And today, we are so accustomed to it, we don’t notice. And, if we did, large demographics wouldn’t care. Generations Y and Z are products of the post-private era.

Clinton was the first president of that era. He was a politician who smudged the demarcation lines between statesman and spectacle, between leadership and sheer likeability. He didn’t fall from grace so much as slide into a new kind of fame, the kind in which the fall itself was an essential part of the entertainment. The sleazy kind.

Lewinsky, more than anyone, bore the cost. She didn’t crave celebrity status; it was affixed to her. The affair, the dress and the endless denials weren’t just political moments. They were cultural markers, showing the world that no one, not even the president of the US, is exempt from unwelcome, permanent exposure.

[Ellis Cashmore’s “The Destruction and Creation of Michael Jackson” is published by Bloomsbury.]

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment