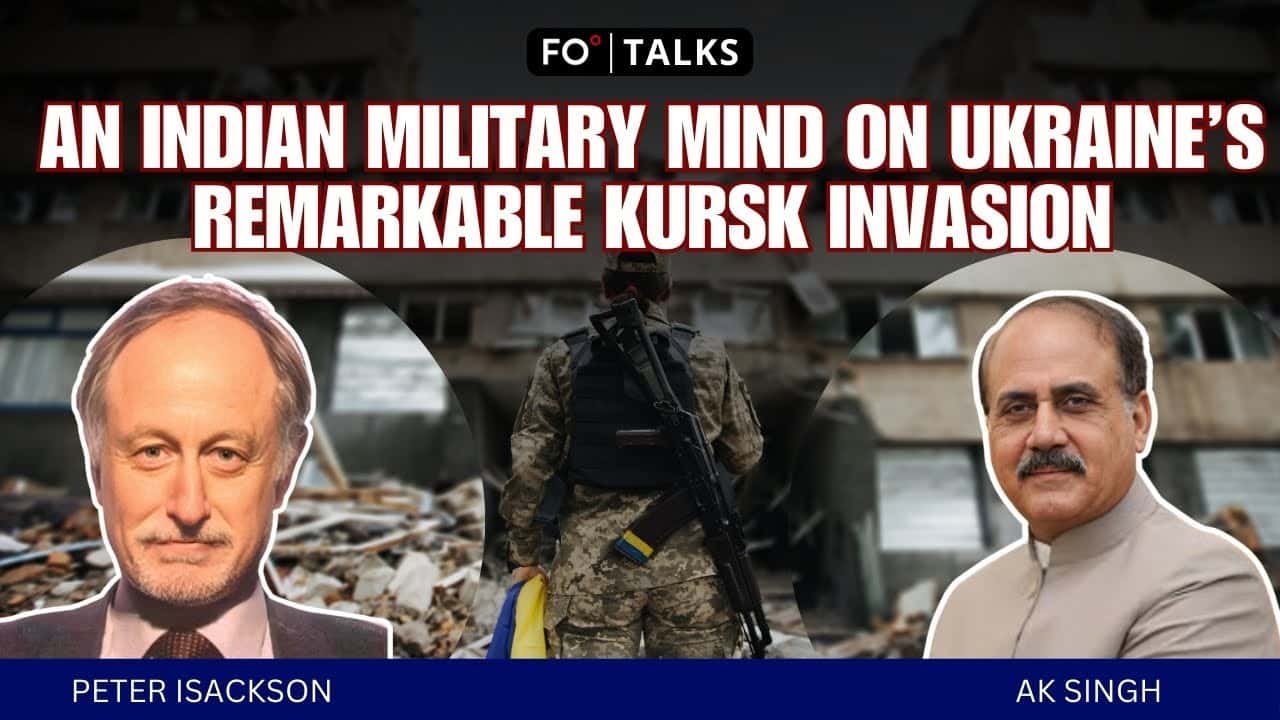

This conversation between Fair Observer Chief Strategy Officer Peter Isackson and retired General AK Singh, a seasoned Indian military commander with deep ties to Soviet, NATO and Russian commands, offers a wide-ranging strategic assessment of the Ukraine conflict. Singh’s insights explore not only the war’s military dimensions but also its geopolitical roots, global ripple effects and what it reveals about shifting power structures.

A war that “should not have been”

Singh opens with the assertion that the Ukraine war was avoidable. He blames “international centers of compellence” — namely, US neoconservatives and a compliant EU/NATO bloc on one side, and Russia on the other. Ukraine, he argues, is the real victim: a “means” caught in the middle and devastated. He criticizes Western media for shaping public perception and pressuring social media platforms to take sides. He questions the West’s moral consistency, citing the unequal outrage over civilian deaths in Ukraine versus Palestine, Afghanistan, Syria or Libya.

In terms of economic warfare, Singh calls sanctions a “double-edged” tool that is ineffective against Russia’s resilient “fortress economy.” He points out that India has drawn lessons from the conflict, bolstering its defense self-reliance and maintaining a pragmatic foreign policy. Isackson agrees that the war could have been avoided and faults Western media for ignoring the historical buildup.

Red lines and long-range risks

The discussion turns to a crucial question: Should the West authorize long-range strikes into Russian territory? Isackson asks what this would mean for the war. Singh calls it a “critical juncture.” European countries may support the move, but the US remains cautious due to Russia’s vast nuclear arsenal and doctrine that allows using “all means” if the state is threatened. He warns that such attacks could corner Russia, potentially triggering a drastic response. Still, he expresses hope that cooler heads will prevail.

Politics and the path to escalation

Isackson raises the role of US politics in shaping the war’s trajectory, especially in the face of the US’s 2024 elections. He suggests efforts may be underway to prolong the conflict until November. Singh agrees, calling the presidential election an “overbearing influence.” He notes internal US divisions, with the Pentagon and Department of Defense reportedly opposed to escalation, while the State Department and intelligence agencies push for it. He expresses concern over CIA Director William Burns’s support for risky decisions, despite his understanding of Russian red lines.

Singh emphasizes that Ukraine’s fate is tethered to US decisions, not Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s leadership, which he calls “delusion” in the eyes of the Global South. He doubts the strategic value of delivering F-16 fighter aircraft or launching operations like the Kursk incursion, asserting that “everybody understands that Russia cannot be defeated.” The key question is how much Russia will gain — especially securing Ukraine’s Donbas region and halting NATO expansion — before the war ends.

Propaganda, publics and power

Isackson challenges the disconnect between Singh’s assessment and official Western rhetoric that insists on Ukrainian victory. Singh points to internal Russian unity, comparing current public support for Putin to wartime solidarity in World War II. He urges the West to stop chasing illusions and instead pursue backchannel diplomacy — especially between the US and Russia. He criticizes Western narratives that paint negotiation as “appeasement,” stifling chances for real peace.

Singh stresses that basic trust between Russia and the US has eroded. Citing retired German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s remarks that the Minsk Accords merely “bought time,” he argues Russia will not fall for such tricks again. He anticipates a turning point within months, as Ukraine’s capacity to sustain the war continues to weaken.

Kursk: tactical gain, strategic mistake

Isackson and Singh sharply analyze the Kursk operation. Singh doubts Ukraine could have launched it without Western backing. Though Ukraine gained territory, he sees no strategic benefit. With no coherent defensive line and mounting casualties, Ukraine faces a dire choice: entrench and risk losing supply lines, fall back to a shallower position or try to rescue troops from Donbas. He highlights the importance of the Ukrainian city of Pokrovsk as a logistical hub.

Isackson mentions that Western officials justify Kursk as a “morale boost,” but Singh sees it as a mistake without a defined “end state.” He contrasts MI6’s more cautious tone with Burns’s more hawkish stance. While the US offers rhetorical support, he argues that Ukraine bears the actual costs — “half a million dead,” mass displacement and destruction — while the US risks little.

Regime change fantasies and geopolitical blindness

Talk of regime change in Russia is brushed aside. Singh sees strong support for Putin and no viable challengers. Isackson compares this to Vietnam, where the US prolonged an unwinnable war. Singh says the US elite isn’t being honest with the public and that sanctions have failed to hurt the average Russian. He laments a lost opportunity for post-Cold War reconciliation with Russia, which instead “was poked” into closer Chinese ties.

He argues that US foreign policy is captive to the military-industrial complex, which profits from prolonged conflict. He contrasts this with India’s emphasis on peace and diplomatic flexibility. Drawing on his experience with both Soviet and NATO forces, Singh finds it surprising that so few retired US military officials publicly challenge prevailing policy.

The rise of BRICS and a multipolar order

Isackson brings up BRICS and its growing appeal. Singh says the Global South no longer wants to be pulled into superpower rivalries. BRICS, representing a large share of the global population and GDP, offers an alternative where their interests are better safeguarded. He predicts that US unilateralism will recede and sanctions will push countries toward a new parallel economic system.

India’s decision to buy Russian oil is cited as pragmatic and in its national interest. Isackson notes BRICS’s challenge to the dominance of the US dollar. Singh adds that the outdated structure of institutions like the UN Security Council must change. It’s “scandalous,” he says, that India still lacks a permanent seat.

A final warning: eyes on the Middle East

In closing, Singh argues that Ukraine is unlikely to cause a global catastrophe, but the Middle East might. He warns that one incident involving Israel and surrounding powers could escalate uncontrollably. Isackson says that today’s youth seem desensitized to nuclear threats — unlike his generation, which was shaped by events like the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Singh praises Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán for bluntly acknowledging the risks and criticizes other European leaders for underestimating the dangers. Isackson agrees and sees leaders like Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as more volatile than Zelenskyy. He warns that both are trying to draw the US deeper into their wars.

Singh closes by noting Putin’s restraint — seen by some as fear, but which he views as a deliberate effort to avoid crossing a dangerous line. Isackson recalls that Putin once proposed a security framework to avoid war, which the West has largely ignored.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment