Information, as powerful as it is, belongs to everyone and can help in individual self-determination.

At the center of any WikiLeaks discussion lies Julian Assange, the platform’s founder who has been embroiled in scandals and accusations of misogyny, amongst all else. Lesser known is the story of the women involved in the WikiLeaks phenomenon, as whistleblowing is an area of activity that, as Renata Avila, Sarah Harrison and Angela Richter write in Women, Whistleblowing, WikiLeaks: A Conversation, is “widely perceived as heavily male dominated.”

This is because the mainstream media heavily focuses on key male players — not just Assange, but also journalist Glen Greenwald, whose work on the NSA surveillance disclosures by whistleblower Edward Snowden has brought them both into the international spotlight. Even Chelsea Manning, despite being a transgender woman, is often referred to as a “he.”

This is one of the notions brought up in the foreword of a book based on a conversation sparked between the women involved with WikiLeaks. Harrison, an acclaimed journalist; Richter, a Croatian-German theater director; and Avila, a celebrated Guatemalan human rights lawyer, are all women who have had prominent roles working within WikiLeaks. For instance, Harrison was at the heart of the Snowden revelations and accompanied him in his escape from Hong Kong to Moscow. Yet, as Richter points out in the foreword, instead of describing Harrison as a “brave, independent journalist,” she was often referred to in the media as “an ‘assistant’ or ‘friend’ of Assange.”

Whatever your thoughts on WikiLeaks, it’s undeniable that it is perhaps one of the most game-changing institutions of this century. Women, Whistleblowing, WikiLeaks, published by OR Books, at least attempts to throw some of the spotlight back onto the women who have had an active and prominent role in the unfolding of events that have changed national security discourse today.

A Conversation

So, what does a conversation look like between Harrison, Richter and Avila? While all three touch on the absence of women from coverage of WikiLeaks and the discourse surrounding it, this is not what dominates their conversation. They consider the broad foundational and structural problems facing society that has necessitated an organization like WikiLeaks, the challenges of achieving progress as well as having more nuanced discussions about privacy and surveillance.

First, talking about what got them involved in the organization, there appeared to be common ground that all three couldn’t see any effective way to implement change using the same tried and tested methods. While all three women came from different disciplines and backgrounds, the ineffectuality of traditional forms of protest hit a chord for all of them. As Richter explains: “I had become aware that the classical forms of activism just didn’t work anymore. It seemed to me that the Western governments will quite happily let the protesters demonstrate, knowing that such demonstrations will not be able to affect meaningful change.”

All three saw WikiLeaks as something new to shake up the old system. For Richter, the idea seemed simple and also powerful, to have an “anonymous portal” where people can safely post information.

For Avila, her experience growing up during the war in Guatemalan meant she had already seen one resistance movement buck the status quo. In the 1990s, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, after a successful uprising, regained control of land in Chiapas, Mexico. At that time, the Zapatistas were protesting against the North American Free Trade Agreement, which cancelled an article in Mexico’s constitution that protected native communal land holdings.

Alvera says that they galvanized international solidarity by using the internet to show evidence of what was happening in Chiapas, which she believed worked because it caught the world by surprise. She also believed that this was then achieved by WikiLeaks when it released the “Collateral Murder” video which depicts two US Apache helicopter crews indiscriminately shooting down several Iraqi civilians, including two Reuters journalists, in Baghdad in 2007.

For Harrison, the organization worked in the way she related to: using raw data, facts and documents and allowing these to empower people. WikiLeaks for all three women thus presented a new and possible way to affect change.

What Gets Out?

Another point not readily addressed in the mainstream media emerged during the discussion of the Snowden leaks. It showed that there is a divergence in opinion when it comes to the question of what to leak and who gets to decide that.

Got my own printed copy today! Thank you @orbooks.

“Women, Whistleblowing, Wikileaks” by @avilarenata, #SarahHarrison & me.

Available online here: https://t.co/i79IfIWWma… pic.twitter.com/i75HyIgDO8— Angela Richter 🐘 (@AngelaRichter_) February 14, 2018

The authors believe that the fact that journalists disclosing the leaks have held back material and heavily redacted what is published flies in the face of what Wikileaks is about. Referencing published articles that included some of the leaks, there was discontent that much of the information remains redacted and undisclosed. Harrison noted: “These journalists are assuming that the public needs a journalistic filter on information to which we are all entitled to have access. They even seem to be celebrating the fact that they redact the material they receive.”

Instead, Harrison, Avila and others believe that information, as powerful as it is, belongs to everyone and can help in individual self-determination. It’s the basis on what WikiLeaks is about and a point that has separated the organization from pursuing further media collaborations. But the point becomes pertinent when the authors talk of the cross-cutting issue of the “global south’s” role and the impact it’s felt from both disclosure and non-disclosure. In many ways, US journalists were concerned with the local struggle — the impact on Americans and looking at the leaks through the prism of US law.

Avila says that “with millions of documents pending publication, it is reasonable that journalists will wonder and seek access to those documents because, for Latin America, there is the possibility that there is significant material on the War on Drugs in the NSA documents. If the documents had been published in their entirety we could easily find out, but, instead, we are still awaiting publication.”

Latin Americans may not have shocked by the NSA revelations because, as Avila says, their rights have been eroded by the US Drug Enforcement Agency in the war on drugs. Also noting that there may not be anything in the documents concerning the war on drugs, Avila’s point is that they don’t know because the documents are not out there in their entirety. By choosing what is only of importance to the US, journalists appear to be ignoring what is of importance to everyone else — and they’re doing so through the prism of US laws and standards, in direct conjunction with their government.

Harrison says that “There’s real prejudice against non-Western countries … dissidents outside of the West are seen as unimportant ‘brown people.’” That the NSA leaks got so much traction could therefore also be down to the impact white males in the developing world felt on themselves. Rather than being responsible, selectivity of publication is actually discriminatory.

Is It Just Middle-Class White Men Who Suffer?

Unlike Assange, however, it appears at least that the women from WikiLeaks have avoided the pursuit of law enforcement. The reasons for this could be that they’re just too “cunning,” as Avila jokes in the book. But straight on from the joke, they talk about other marginalized communities, and that even though they are not talked about in the media, their struggle can be even greater and the consequences high too.

For instance, Avila draws a comparison between the two activists, Aaron Swartz — a middle-class white man from the US, and Bassel Khartabil — a Palestinian from Syria. The two men engaged with the same issues, working on open source information, and knew people in the same circles. However, when Swartz committed suicide, it became mainstream news, while Khartabil — the recipient of Index of Censorship’s Digital Freedom Award executed by the Syrian government in 2015 — garnered little media interest during his incarceration.

When it comes to women, the discussants agree that their contributions are often dismissed. This ironically plays into their favor, because it gives them greater room to act. Conversely it also means their sacrifices are not acknowledged.

Avila says that “in my country, the fight against the mining industry is led by women community leaders, and there are now attempts to charge them with sabotage and terrorism just for defending their territories … The story is not covered by the media because reporting on women fighting against mining corporations conflicts with the corporate capture of the media.”

From Facebook to Google and the dangerous power now held in Silicon Valley, the conversation between the three women, facilitated by Joseph Farrell, is one of speaking truth to power. It uncovers layers to the WikiLeaks debate, showing that activists still have their work cut out for them, and they’re continuously having to innovate and come up with creative and surprising ways to shock people into paying attention.

The premise of the conversation also highlights a key point: The fact that women are excluded from media conversations about WikiLeaks is another symptom of the endemic problem of social and economic inequality that sidelines women along with many other traditionally marginalized groups – minorities, those in the developing world, the poor. Ideas that appear to be solving problems, like WikiLeaks, need to be proactively inclusive, otherwise they could end up harboring those same inequalities.

The conversation isn’t a long one, but it may just draw you in and help you voice your own opinion.

*[Women, Whistleblowing, WikiLeaks is available from OR Books.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

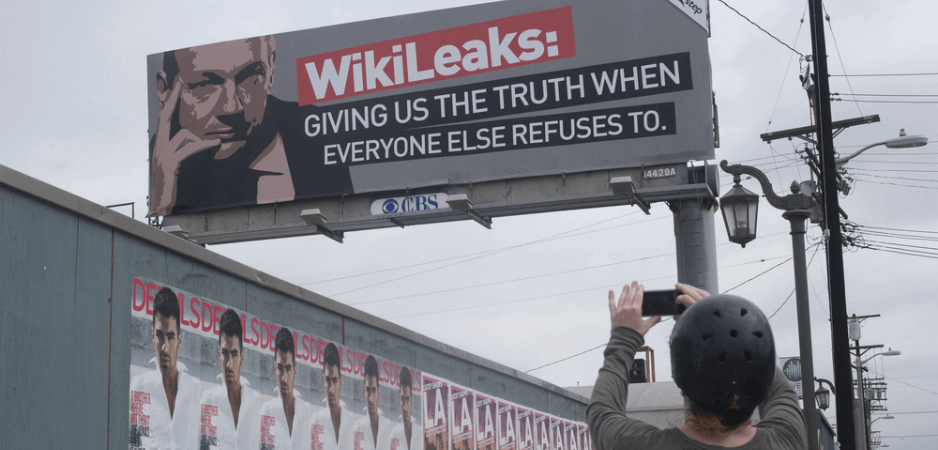

Photo Credit: Richard Frazier / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.