War has remained a near constant and destructive force in the history of human development.

Background

According to Stephen Pinker, we live in the safest of times. In his book, The Better Angels of our Nature, he writes: “The decline in violence may be the most significant and least appreciated development in the history of our species.” That is, in the last 200,000-odd years of our existence on earth, we have now reached a point where governance, economic progress and education have brought us to the peak of humanity.

In the history of human development, war and conflict have remained a nearly-constant, destructive force ripping through the social fabric. According to some estimates, in over 3,000 years of recorded history, less than 300 years have been peaceful. Conquest, rebellion, civil strife, slave trade, wars of succession and secession, disputes over territory and natural resources, ideological struggle — these concepts have throughout the centuries trumped the value of human life, and continue to do so till today.

Pinker’s argument may be disputed, particularly if one takes into account that World War II was the deadliest conflict of the last 1,000 years, having claimed over 60 million lives in just six years. By comparison, Genghis Khan’s Mongol invasions, which ravished Eurasia in the 13th century, killed at least 40 million people in the course of a hundred years. Although estimates of this kind are predictably difficult, there have been suggestions that up to 4 billion lives were lost to war since records began. Between 1900-90 alone, over 40 million soldiers and 60 million civilians died in conflicts.

Yet there is a consensus nowadays that interstate and civil wars have declined since the end of the Cold War — the post-World War II period known as the “Long Peace.” The Upsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) estimates the average number of conflicts worldwide stand at around 33-37 in the past decade. These, according to data gathered by Pinker, claim less than 1/100,000 of the world’s population — a substantial drop from 300/100,000 during World War II or even the low teens in Vietnam.

Given the devastating death tolls of wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, with ongoing conflicts in Nigeria, Somalia, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ukraine and multiple wars between Israelis and Palestinians — among numerous others — it is difficult to buy into the idea that war is out of fashion. With the prevalence of 24-hour news and the uncensored freedom of the Internet, suffering is brought ever closer to us, and seems to be omnipresent in its horror.

The brutal conflict in the DRC, which has claimed over 5 million lives since 1998 — the largest death toll since the Second World War — received 16 minutes of coverage on CNN and 29 minutes on the BBC in the entire year of 2000, compared with over eight and nine hours dedicated to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the same period.

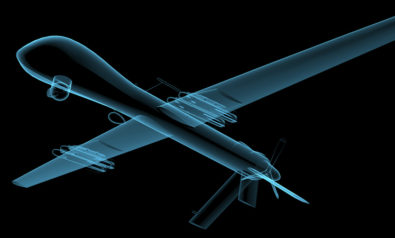

There have been many suggestions that these “new wars” of the late 20th century have signaled the death of modernity, as the failure of nation-states and the rise of identity politics are equated with the failure of Enlightenment thought. Globalization and the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) is often viewed as a new modus vivendi, one in which transnational actors mete out violence through technologically advanced weapons such as drones — a new, postmodern style of war that is more removed from the reality of horror and brutality, producing ever higher civilian suffering.

Former Secretary General of the United Nations Boutros Boutros-Ghali famously quipped that television has changed the way we react to crises. Indeed, the so-called CNN effect has been hotly debated, and widely credited with humanitarian interventions in places like Somalia.

Yet the majority of the world’s most devastating conflicts go largely unreported — with “silent emergencies” in places such as East Timor, Liberia, Angola or Sudan falling under the radar. The brutal conflict in the DRC, which has claimed over 5 million lives since 1998 — the largest death toll since the Second World War — received 16 minutes of coverage on CNN and 29 minutes on the BBC in the entire year of 2000, compared with over eight and nine hours dedicated to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the same period. Given that Africa constituted some 90% of combat deaths in the world a decade ago, with the balance shifting to the Middle East and Asia more recently, how much do we really know, or care, about the true extent of human suffering?

Why is the Issue of War Relevant?

War, as Carl von Clausewitz famously wrote, is “an act of violence pushed to its utmost bounds” and to “introduce into the philosophy of War itself a principle of moderation would be an absurdity.” Yet the liberal postulate that democracies do not wage wars against each other has, to a large degree, spared those of us lucky enough to have been born in the West from unthinkable misery of all-out war.

But if we consider the number of veterans of just the two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — 2.8 million in the US alone — the human cost of conflict is brought home to all of us with the tragedy of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dreadful injuries and social injustice. If we consider the 50 million refugees fleeing conflict zones worldwide, running from systematic abuse (some 48 women are raped every hour in the Congo), children orphaned and traumatized, the exorbitant military budgets begin to look not only questionable, but immoral. Since 2008, according to the Global Peace Index, 111 countries have seen levels of peace deteriorate, with only 51 nations seeing an increase.

Sigfried Sassoon, writing about his experience in the First World War, sneers at the crowd watching soldiers march by: “Sneak home and pray you’ll never know / The hell where youth and laughter go.” To this day, for a large part of the world’s population, this prayer goes unanswered.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Well written. Liked the analysis: The two World Wars were the last interstate conflicts where belligerents were more or less evenly matched. ….. ANd that: In the current conflicts that are raging, particularly in Iraq and Syria, the combatant/non-combatant distinction has more or less disappeared. Civilians have been targeted by belligerents. Looking forward to Part 2.