Euroskepticism is often discussed, particularly in the context of the ongoing Brexit debate, as a right-wing political cause. However, the recent maneuverings of the European authoritarian right ahead of the EU parliamentary elections in May suggest an attempt by the radical right to seize the institutional levers of Europe. Recent articles in The New Yorker and the New Statesman have warned of the development of a “pan-European” authoritarian right looking to reshape the European Union in its image. Former White House chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon’s Brussels-based The Movement was an attempt last year to coordinate such a constituency.

A historical precursor to these contemporary radical-right visions of Europe, and a British one at that, can be found in the shape of Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement (UM) between 1948 to 1973. The UM was the vehicle, at least for a time, of his attempt to return to politics following the Second World War. Despite the growing interest in transnational history and in non or anti-liberal internationalism, outside of the field of studies of fascism and the far-right the UM’s Europeanist vision often gets overlooked.

Europe, a Nation

As leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) from 1932 to 1940, Mosley was interned in May 1940 under suspicion that he might act as a potential fifth columnist. He was released from prison on health grounds in 1943. While some of his unrepentant followers returned more or less immediately to political activism, Mosley bided his time. Over the course of 1946 and 1947, he began to gather the disparate groups of his followers together.

In publications like the Mosley Newsletter and his second postwar book, The Alternative, Mosley set forth his revised creed. Mosley criticized interwar fascism as excessively nationalistic. The “National Socialist or Fascist movements” of the 1930s were indicted for their “narrow” focus “upon securing the interests of [their] own nations.” In the future, he argued, the goal should be to foster “the Idea of Kinship,” essentially cultural and racial solidarity between Europeans around the world.

In case this in any way resembled the sentiments of supporters of the League of Nations or the incipient UN, Mosley provided some clarification. This was not to be the “old Internationalism” which, according to Mosley, preached the doctrine of absolute equality between “the savage” and “the European.” Indeed, Mosley’s plan to unite Europe was to be based on the domination of the very people he considered “savages.”

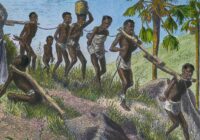

His European vision, referred to by the slogan “Europe a Nation,” was to be built on the intensified colonial development of Africa, which was to serve as “the Empire of Europe.” To an extent, this represented the extension of Mosley’s interwar plans for a “Greater Britain”: an economically unified British Empire insulated from the interference and crises of the international financial system. Now, the “Greater Empire” of Europe was to be governed along authoritarian lines provided with an “untapped” African source of raw materials as well as a guaranteed market for goods.

Graham Macklin has noted that Mosley’s “Euro-African” plans betray “the influence of the German Colonial Office and the geopolitics of Dr Anton Zischka, a Nazi ‘expert’ on Lebensraum.” Moreover, Mosley was theorizing about a European imperial revival at the same time as similar ideas were being considered by the postwar British state. Ernest Bevin, foreign secretary in the 1945-51 Attlee government, was keen to establish a united Europe under Anglo-French leadership, bolstered by the material resources of Africa, in order to check the influence of America and the Soviet Union. Beset by economic problems and poor relations with France, these plans were never realized.

While the Labour Party’s plans for Africa were based on Fabian ideas about colonial development and the gradual democratic political advancement of Africans, Mosley saw “Euro-Africa” as an authoritarian, white supremacist configuration. Macklin has aptly summarized the UM’s plans as “no more than a geographically enlarged National Socialism.” Britain, as Mosley rather crudely put it, had no “’sacred trust’ to keep jungles fit for negroes to live in.” He believed in trusteeship only in so far as it was “on behalf of White civilisation.” Britain was to conduct itself not in the humanitarian spirit of Fabianism, but in the bold and coercive spirit of Rhodes and other British imperial pioneers.

In collaboration with South Africa’s ex-government minister and Nazi sympathizer Oswald Pirow, Mosley formulated plans for a continent-wide extension of apartheid. The plan was to divide Africa into three parts: one for whites, the “central tropical” region for Africans, and a northern “Islamic Africa.” While Mosley and other UM members constantly maintained that this was to be an arrangement of separate but equal partners, they stressed the subordinate position of black Africans.

The precise way in which the African “cake” was to be cut was also unclear; Mosley maintained that “all of Africa where the white man can live belongs to the European.” The UM’s enthusiasm for “white” Africa later saw them support South African apartheid and back Southern Rhodesia when it withdrew from the Commonwealth in 1965.

Beyond Comprehension

As a political movement, however, the UM amounted to very little. Mosley’s followers — unrepentant fascists accustomed to the nationalism of the interwar BUF — were perturbed by his superficial internationalist turn. In his talk of going “Beyond Fascism, beyond democracy,” some of the old guard felt he had gone “beyond comprehension.” Mosley himself seemed to lose interest in the UM and, despite returning to stand unsuccessfully in a series of by-elections, spent much of his time abroad, moving to Ireland in 1951 and to France two years later.

Rather than heading a small movement struggling against anti-fascists on the streets of Britain, Mosley instead preferred to travel the world posing as a leading intellectual of the European radical right. To this end, he rubbed shoulders with Spanish fascists, exiled Nazis in Argentina and other European neo-Nazis, contributed to the European Social Movement’s journal Nationa Europa, and founded his own “high-brow” journal, The European.

In 2019, Mosley’s European vision does not feel so distant as current affairs increasingly come to resemble the darker parts of history. In Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Romania, the United Kingdom and elsewhere, populist right-wing parties are coming together ahead of the elections for the European Parliament. With the revelation that one in four Europeans votes populist, and that populism tending ever more toward the radical right, it remains to be seen how these elections will go. While a victory for the radical right is highly unlikely to result in a neo-imperial union of Europe ruling Africa, the consequences for people of color and migrants will no doubt be dire.

*[The Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right is a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.