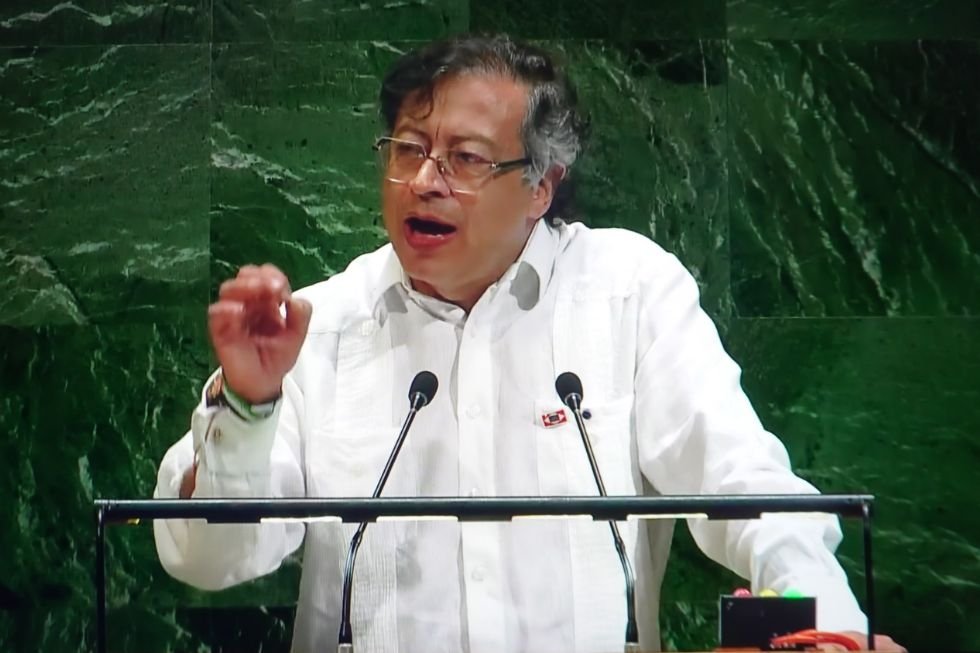

In September, Colombian President Gustavo Petro delivered two controversial speeches at the 2025 United Nations General Assembly in New York. The first was his speech at the podium to a crowd of international leaders, where he called for the creation of a UN army to liberate Palestine and denounced US attempts to intervene in Venezuela and Colombia.

Following his speech, he addressed a gathering of pro-Palestinian protesters and journalists outside the UN building using a megaphone, where he urged US soldiers to disobey President Donald Trump’s orders. His exact words were:

The people united will never be defeated. We are going to present a resolution ordering the United Nations to form an army to save the world, whose first task will be to liberate Palestine. From here, from New York, I ask all soldiers in the US Army not to point their guns at humanity. Disobey Trump’s orders, obey the orders of humanity.

Washington responds: visa revocation and diplomatic fallout

In response, the US State Department announced on X that it was revoking Petro’s visa due to his “reckless and incendiary actions.” This is the second time a Colombian president has had his visa revoked by the US. The first was Ernesto Samper during former US President Bill Clinton’s first term in 1996, due to his alleged connection to the Cali drug cartel and Colombia’s refusal to extradite drug traffickers. In August 2025, Arturo Arias, the ex-president of Costa Rica and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, stated that the US had canceled his visa after he voiced his criticism of Trump on the internet.

Petro’s visa cancellation appears to have added him to the list of current or former presidents banned from entering the US. This list also includes Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, who was unable to attend the UN assembly for this same reason.

A fractured relationship: Colombia and the United States through history

The revocation of Petro’s visa is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the United States’ decades-long challenging relationship with Colombia, a pivotal nation in the South American political landscape. This relationship is typically portrayed by endeavors to combat drug trafficking, the contradictory romanticization of figures like Pablo Escobar by popular culture — as depicted in the Netflix series Narcos — and the cloaking of the shared history of North and South American decolonial struggles for independence and the contributions of figures like Gabriel García Márquez (the Colombian Nobel Prize winner in literature in 1982 and author of One Hundred Years of Solitude [1967]).

More specifically, setting aside magical realism, the relationship between Petro and Trump has been brief yet intense, and it has been defined by a series of mutual accusations that began in January of this year.

Petro initially rejected two planes carrying Colombian deportees, arguing that they were not receiving dignified treatment. However, the two countries later reached an agreement amid threats of tariffs.

Petro’s rhetoric of resistance and the echo of Bolívar

Petro chose X to address the US president directly. In this missive, which begins with a confessional tone, he writes:

Trump, I don’t really like traveling to the US. It’s boring, but I must admit that there are some good things about it … I don’t like your oil, Trump. You’re going to destroy the human race because of your greed. Maybe someday, over a glass of whiskey, which I accept despite my gastritis, we can talk frankly about this. But it’s difficult because you consider me inferior, and I’m not, nor is any Colombian.

In his lengthy letter, Petro suggests taking a historical journey and recalls the US intervention against Chilean President Salvador Allende, which elevated Augusto Pinochet to power. He appears to be defending Colombia’s global standing, highlighting aspects such as “Colombia is the heart of the world, and you misunderstood that. This is the land of yellow butterflies, the land of Remedios’ beauty,” drawing a literary parallel to one of the most stunning scenes in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Among other references to the past struggles of the US civil rights movement, Petro contradicts his willingness to share a whiskey with Trump when he adds, “I do not shake hands with white slave owners. I shake hands with white libertarians, the heirs of Lincoln, and black and white peasant boys of the United States.”

In this X message, Petro uses the plural form of “Americas,” making it clear that Colombia will no longer look northward. He also mentions Venezuelan statesman and military officer Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), the hero of South American independence — also known as El Libertador, “the liberator” — highlighting the shared, collective and plurinational history of the Americas, which he believes Trump does not represent.

He draws attention to Trump’s immigrant past and lack of Native American ancestry, referring to him as an “immigrant” as well: “I raise a flag and, as Gaitán said, even if I am alone, it will continue to fly with Latin American dignity, which is the dignity of America, which your great-grandfather did not know, but mine did, Mr. President, immigrant in the United States.”

Although several months had passed and the scenario was different, Petro maintained the core sentiment of his aforementioned X epistle when he addressed the UN General Assembly. His speech was equally assertive and combative.

Climate, conflict and calls for a new world order

He addressed statements made by the US government one week prior to the assembly, in which they claimed that neither Venezuela nor Colombia was cooperating in the fight against drug trafficking.

These statements were made amid the sensitive situation involving the US troops’ launch of a missile at a small boat in Caribbean waters in early September. The US alleged that the ship was trafficking drugs. Standing before the UN, Petro shared that an investigation was underway to determine if Colombian civilians were aboard the boat. He stressed the importance of initiating due process against the US officials who ordered the missile strike.

From the podium, Petro provocatively proposed that “Drug traffickers live elsewhere. They live in New York, a few blocks away, and in Miami. They make deals with the DEA. They live in luxury, not poverty. Not in the Caribbean or Gaza.”

The Colombian President also devoted much of his speech to discussing the climate crisis and clean energies, such as green hydrogen and decarbonization. He praised the “enormous absorbent sponge of the Amazon rainforest”. He also accused the “most powerful government in the world” of not believing in science: “That is called irrationalism, and it was that same irrationalism that filled Hitler’s Germany.”

When it was his turn, Trump devoted a significant portion of his address to the UNGA to criticizing renewable energy and rejecting the scientific consensus on climate change. He claimed that clean energy sources, such as solar and wind power, are less effective and more expensive than fossil fuel alternatives.

Speaking from the UN podium, Petro adopted the tone of the Latin American independence heroes he mentioned in his January letter when he proposed the creation of a UN armed force. He made statements such as, “There is no superior race, gentlemen. There are no chosen people of God. Neither the United States nor Israel are chosen by God. Ignorant fundamentalists of the extreme right think that way. The chosen people of God are all of humanity.”

After this, he added that diplomacy had run its course and urged the UN to establish an armed force to protect the lives of Palestinians: “Words are no longer enough. It is time for Bolívar’s sword of liberty or death because they are not only going to bomb Gaza and the Caribbean, they already are, they are attacking humanity, which cries out for freedom.”

From Bolívar’s dream to a divided continent

In addition to his defiant tone toward Trump and his call for the US military to rebel against him, Petro’s recent public statements are notable for their repeated mention of Bolívar. During his visit to New York, he granted an interview to the BBC News World based in Manhattan. The words chosen for the headline of the interview’s video were “Trump has failed to understand that Bolívar’s children are not subordinates.”

Bolívar, the “Liberator of America,” fought against the Spanish crown for 20 years to achieve independence for Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Born in Caracas to a family of Creole nobility, Bolívar received a European education. He then brought what he had learned about liberation in France to the other side of the ocean.

In August 1819, Bolívar crossed the Andes mountain range and defeated Spanish troops in the Battle of Boyacá, achieving independence for the region of New Granada, now Colombia. Interestingly, in 1691, Palenque, located in present-day Colombia, was the first colonial settlement to free African slaves, who became the first officially freed black slaves anywhere in the Americas.

One of Bolívar’s greatest hopes was a grand confederation of all the former Spanish colonies in America, inspired by the United States’ model. To this end, in 1826, he convened the Congress of Panama to organize a confederation of American nations that would support and cooperate with each other for the common good. However, as we know, he did not achieve his goal.

Nowadays, the differences among countries in the region continue. In the current state of affairs, Trump is favored by Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa and Argentine President Javier Milei, who distance themselves from other regional leaders, such as Chilean President Gabriel Boric and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, who oppose US interventionism.

Domestic backlash and regional uncertainty

2026 will be a pivotal year for South American politics, with upcoming presidential elections in countries such as Peru, Brazil and Colombia. A map that has always been of strategic imperial interest to the United States, as evidenced by its long history of interventions in regime changes. According to the Harvard Review of Latin America, “In the slightly less than a hundred years from 1898 to 1994, the US government has intervened successfully to change governments in Latin America a total of at least 41 times.”

Since the late 20th century, the international relations between Colombia and the United States have been marked by bilateral efforts against drug trafficking, such as the Plan Colombia, signed in 1999 between the administrations of Colombian President Andrés Pastrana Arango and Clinton, who signed it into US law as an approval of an aid package to both keep drugs outside the US shores and “help Colombia promote peace and prosperity and deepen its democracy.”

A fundamental aspect of the Plan Colombia was indeed supporting the disarmament of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country’s largest insurgent group, founded in the 1960s, and the National Liberation Army (ELN), both designated as foreign terrorist organizations by the US State Department.

Álvaro Uribe, elected Colombian president in 2010, began formal peace talks with the FARC in 2012. It wasn’t until US President Barack Obama’s and Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos’s terms that the peace process actually reached its culmination in Colombia, after only four rounds of negotiations, and with the governments of Chile, Cuba, Norway and Venezuela as hosts, mediators and observers.

The peace agreement called for the guerrillas to hand over their weapons to a UN commission. It also contemplated that international aid, especially from the United States, would be needed to invest in neglected rural areas and create economic alternatives to drug trafficking.

Unlike the FARC, the ELN remains active, particularly along the Colombia-Venezuela border. During his presidency, Petro has pursued the idea of achieving “total peace” by disarming the ELN. However, negotiations broke down in July after the ELN attacked civilians in the Catatumbo border region.

Due to its involvement in illegal economies, peasant agriculture and the centuries-long indigenous struggle for land sovereignty, it seems that the ELN continues to hold significant social power.

Returning to Petro’s controversial visit to New York, during the BBC News World interview, journalist Tom Bateman asked Petro, “Are you concerned that taking this approach of resisting the US administration risks further isolating your country?” Petro responded that he believes it is President Trump who is isolating himself from the world regarding his position on the Palestinian genocide.

However, a quick review of mainstream Colombian media shows the opposite: the president is facing fierce opposition in his own country. Journalist Daniel Coronell claims that Petro is “building his pedestal as a martyr” and “dragging Colombia down with him.”

Former Foreign Minister Juan Carlos Pinzón told the Colombian media outlet Semana, “This country does not need clowns.” Pinzón, who is presenting himself as a potential presidential candidate and former ambassador to the United States, also said, “We will resolve the issue with Israel immediately.” The newspaper El Colombiano ran the headline, “Petro without a visa but with a megaphone.”

Francia Márquez, the current Vice President and representative of the Afro-Colombian community, is a prominent figure on the left in Colombia. However, in recent months, her relationship with Petro has been filled with disagreements, despite their cordial appearance together at the UN. Adding to the political tension, Manuel Uribe, a future Colombian presidential candidate, was shot and killed earlier this year. US Secretary Marco Rubio blamed Petro’s inflammatory rhetoric for the assassination.

Colombia clearly has its own internal and historical struggles to tackle. Only time will tell how Petro’s continued antagonism toward the United States will affect the Colombian general elections next year and how the region’s new leaders in 2026 will align with or oppose the United States’ imperialistic endeavors.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment