| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

Dear FO° Reader, I read a lot, as you can imagine, just to keep up with Fair Observer’s authors, and sometimes I find the time for a novel, a monograph and even poetry. During my reading, I found this: “Global academic freedom has declined over the past decade for the first time in the last century.” Let that sink in for a minute. I took it from this article from the University of Lund in Sweden. The empirical evidence suggests that improving academic freedom by one standard deviation increases patent applications and forward citations by 41% and 29%, respectively. The results hold in a representative sample of 157 countries over the 1900-2015 period. This research note is also an alarming plea to policymakers: Global academic freedom has declined over the past decade for the first time in the last century. Our estimates suggest that the decline of academic freedom has resulted in a global loss quantifiable with at least 4.0% fewer patents filed and 5.9% fewer patent citations. ArXiv.com Why? What happened? I see a few hypotheses from my home office under a wooden roof in Geneva. Managerial methods intrude in research financing and design, there’s a cultural impoverishment of meaning — knowledge is valued only if monetizable — a rise in authoritarian politics, and what is presented as culture wars, but is in fact a decline of the former, and then extreme ideologies don’t want to hear the other side’s opinions or criticism.

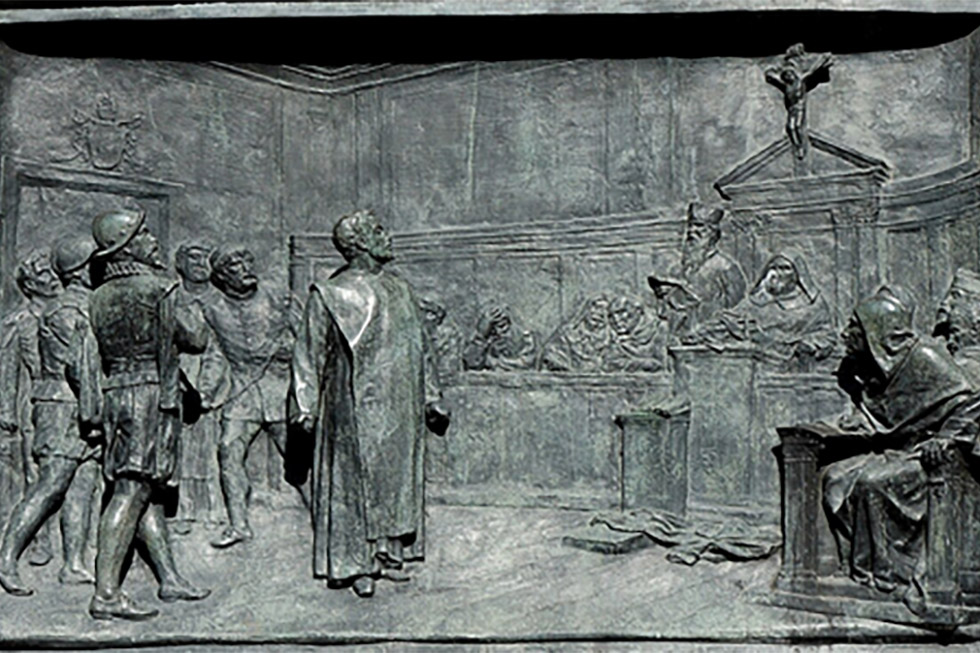

The trial of Giordano Bruno — Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist and esotericist — by the Roman Inquisition. Bronze relief by Ettore Ferrari (1845-1929), Campo de’ Fiori, Rome. The crisis of academic freedom So what’s driving this unprecedented decline? The causes are interconnected, but they begin with a fundamental shift in how universities operate.

Over the last three decades, universities have adopted corporate management models emphasizing productivity, accountability and quantifiable “impact.” While such metrics can improve transparency, they also discourage intellectual risk-taking and curiosity-driven research: the very foundation of innovation and critical thought. Some authors or politicians accuse young people of naiveté because they believe it’s stupid to get into debt for a degree in philosophy or anthropology. In my opinion, the problem lies in who finances universities and why state universities in the US are not more accessible. Europe has an interesting model for funding university education. “Neoliberalism and managerialism in academia — a parasitologist’s take” (Robin B. Gasser, Trends in Parasitology, 2024) is a short piece that shows how academia across disciplines is affected by performance metrics, administrative burdens and reduced freedom. But the problem goes deeper than management structures. These metrics reflect — and reinforce — a broader shift in how we value knowledge itself.

In a society obsessed with short-term utility, disciplines that do not immediately translate into marketable skills, such as philosophy, literature or anthropology, are increasingly dismissed as “unproductive.” This economic reductionism erodes the humanistic core of education, narrowing our collective capacity for reflection and meaning. This economic pressure on universities doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s happening alongside — and intertwined with — a global political shift.

As democratic norms weaken globally, universities are often among the first institutions to feel political pressure. Governments hostile to pluralism tend to restrict academic freedom, censor critical research or defund departments that challenge official narratives — from gender studies to environmental science. Yet it’s not only authoritarian governments restricting academic inquiry. Within democratic societies, a different kind of constraint has emerged.

Some scholars and journalists argue that “wokeism” — or what they call Critical Social Justice ideology — has hardened into a moral orthodoxy, narrowing the space for free inquiry. Others counter that these claims exaggerate rare incidents and distract from larger economic and political pressures on universities. What both sides agree on is that academic freedom now operates under intense cultural scrutiny, with fear and conformity replacing curiosity and debate.

As an example, Project Gutenberg was not born from a grant or corporate lab but from the spirit of public education. Michael Hart, a university student with access to a publicly funded computer network, decided to digitize great works of literature so that everyone could read them for free. Half a century later, that simple act of intellectual generosity remains one of the most radical knowledge revolutions ever made — a testament to what freedom, public access, and imagination can do. How does knowledge actually develop? To understand what we’re losing, it helps to step back and ask: how does knowledge actually develop? What conditions does it need? As humans, as a civilization, we gain greatly from the pursuit of knowledge. So how does it work? And why is it losing ground? Bruno Latour emphasized that knowledge arises through interaction between humans, instruments, institutions and the material world. It’s a process, not a product. And, managerial culture understands processes, so where is the problem? They still want a monetizable product, a final solution instead of a dynamic process. Science is not a set of statements about the world but a set of practices that make the world talk back (Science in Action, 1987). Tim Ingold, an anthropologist, sees learning as movement and engagement rather than accumulation — relational and temporal by nature. “Knowledge is not made but grown, along the paths we travel.” (The Perception of the Environment, 2000). These theoretical insights match what I’ve observed in my own work. In my experience, which is likely closer to yours, dear readers. I believe we can’t learn more about our world if we are not prepared to co-construct it with others, other human beings that experience it (everything) from another perspective. It takes patience and time to listen. But this kind of engaged, patient learning is precisely what’s under threat. John Dewey — the American philosopher, educator and reformer — said, “Every experience is a moving force. Its value can be judged only on the ground of what it moves toward and into.” That means an experience isn’t knowledge in itself — it becomes knowledge when we engage with it, reflect and integrate it into our actions. Watching a video or scrolling through an article is only the first fragment of that cycle. Moreover, all information coming through digital channels has been greatly compressed; digital bandwidth is but a small fraction of what a human can experience in real life. Similarly, engaging in debate is a great exercise, but it is not meant to be as constructive as dialogue can be. Debate is a fight, again a military-inspired tradition where the only possible outcome is the defeat of one of the two parties, or humiliation thereof. Dialogue, on the contrary, is an exploration that allows both sides or more parties to move forward, holding hands if you need an image. When any kind of ideology — whether managerial, religious or moral — takes hold of universities or governments, dialogue is the first thing to disappear. We start to measure, police and moralize rather than listen. In the United States, we’ve seen protests in support of Gaza and the Palestinians being restricted, and books removed from schools because they don’t fit a particular reading of the Bible. In other countries, research on gender or climate change is silenced in the name of tradition or economic interest — different motives, same result: less freedom to think, to question, to imagine alternatives. We’re sacrificing capacity, not comfort The paradox is that by trying to protect people from discomfort — that of questioning beliefs, grammar rules or science methods — or by defending one single truth, we end up making everyone more fragile. Without dialogue and difference, knowledge becomes static. It loses its capacity to evolve. Diversity — in ideas, in people, in methods — is not a threat to truth but its condition of possibility. When we allow many voices to explore the same question, the volume of understanding grows exponentially. So yes, dialogue takes courage. It’s slower than debate — which requires one side to win and overthrow or humiliate the other — messier and sometimes painful. But it’s also what keeps us alive as thinking beings. Every time we choose conversation over confrontation, curiosity over certainty, we protect something essential: our freedom to learn. Until next time, Roberta Campani Communications and Outreach Related Readings The End of the English Major | The New Yorker Academic_Freedom_Index_Update_2025.pdf

| ||||

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news

must

be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and

editors cost money.

So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

| ||||

| ||||

| About Publish with FO° FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact |

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment