| ||

| ||

| ||

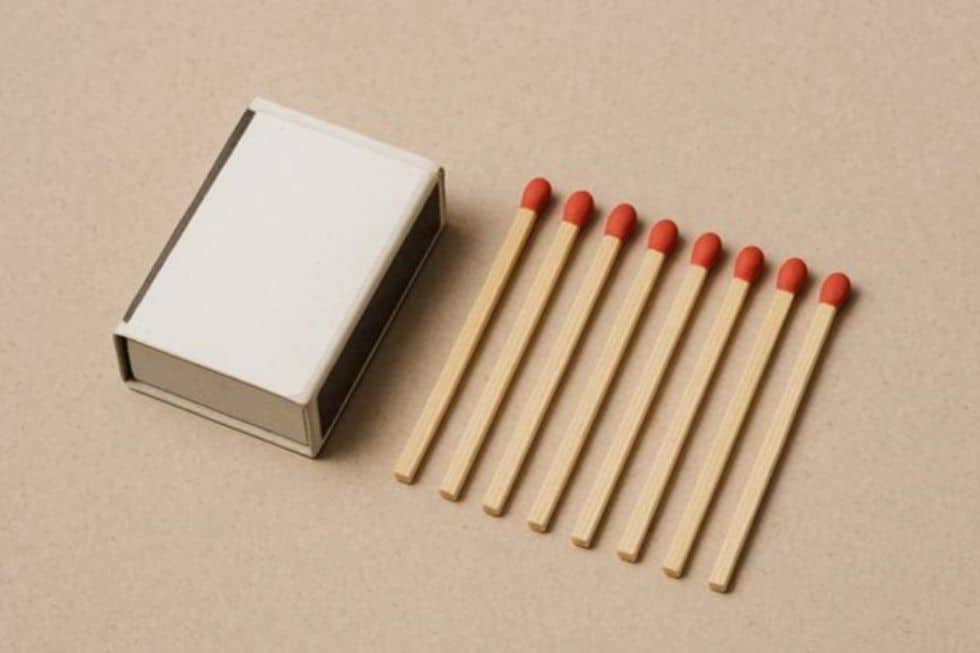

| Dear FO Reader, Humans have long been collectors of numbered truths: The seven deadly sins neatly catalog our moral failings, ten commandments promise divine order, four noble truths map the path to enlightenment. These lists offer comfort in a world that resists such tidy accounting. The laundry multiplies when we’re not looking, work expands to fill every hour, and the news cycle churns without pause. Faced with this beautiful chaos, we become meaning-making machines — and when meaning proves elusive, we invent it. This is where Umberto Eco’s brilliant concept of cogito interruptus becomes illuminating: a rhetorical sleight-of-hand in which reasoning is left deliberately unfinished, and a symbolic cue stands in for a complete argument.  The Alchemy of Seven Matches In one of his essays, Eco asks us to consider a humble matchbox from which exactly seven matches have spilled. For one person, this ordinary event reveals an ill portent: “Seven! The number of divine plagues! The end times are upon us!” For another, the same seven matches shimmer with promise: “Seven! The sacred number of completion! A new cycle begins!” I remember Eco unpacking such examples in his Bologna lectures during my student days in the early 1990s, his eyes twinkling with the delight of revelation. He called this phenomenon cogito interruptus: the moment when a speaker presents a symbolic fragment — like the spilled matches — fixes the audience with a meaningful look, and invites them to supply the ominous or beatific conclusion themselves. Remember the fortune teller at the fair?  The Plagues of Egypt from the Toggenburg Bible, showing humanity's ancient habit of pattern-seeking. This rhetorical strategy drives everything from ancient prophecy to modern conspiracy theories, from New Age synchronicities to polarized political narratives. The same technological breakthrough can appear as either an existential threat or a salvific promise, depending entirely on the symbolic framework through which it is interpreted. Eco’s insight was to recognize that both apocalyptic doom-sayers and utopian visionaries share a common habit: they abandon the discipline of reasoning in favor of symbolic storytelling, equally unwilling to confront ambiguity or complexity. Editors put writing through the crucible of logic and meaning At Fair Observer, we make the tension between semiotic meaning and logical rigor central to our editorial training. Our interns learn to navigate the space where symbols and arguments intersect — where the poetry of meaning-making meets the prose of factual accountability. When faced with a headline like "Policy Change Sparks Crime Wave," they learn to question what causal connection is implied through symbolic framing, rather than simply accepting what is demonstrated by evidence. When editing a politician’s carefully trimmed statement, they develop the instinct to ask what context might restore the full meaning. The past two sessions of the Saturday Editorial Workshop were on logic, led by our trusted Chief of Staff, Anton Schauble. This training produces editors who understand that journalism operates in the challenging space between how things are represented and how they actually are. It teaches that every fact is wrapped in layers of cultural meaning, and that separating truth from its symbolic packaging requires both rhetorical and logical tools. Today, to simplify the process, we can use Large Language Models (LLMs) to help extract arguments or research sources. But we are still learning to use them effectively.  Squid Ink Pasta, by Joy under Flickr Today’s digital dilemma is the rise of the semiotic squid The advent of large language models has given Eco’s warnings new urgency. We’ve unintentionally created what I’ve come to call “semiotic squids” — systems that generate vast clouds of interpretive ink without any substantial framework beneath. Present our seven matches to such a system, and it can just as easily spin them into signs of impending doom or symbols of hope, citing sources and crafting plausible narratives for either position, without any real belief in either. These systems subtly align with the biases of the person entering the prompt — like a faithful servant, they never question the motives. The danger lies not in any particular position these systems might take, but in how perfectly they mimic cogito interruptus — how convincingly they present suggestive fragments and invite us to complete the reasoning according to our own predispositions. In an information ecosystem already drowning in unfinished thoughts, these tools threaten to become engines of mass persuasion, presenting plausible narratives with no actual substance. For readers who value Fair Observer's commitment to nuanced understanding, this analysis gets to the heart of our contemporary predicament. We are living through a crisis of unfinished reasoning, where social media rewards symbolic punches over developed arguments, where political discourse favors meaningful nods and winks instead of completed thoughts, and where even journalism often prioritizes compelling narratives over messy factual complexity. This is why our internship program places such emphasis on cultivating both logical rigor and semiotic awareness. Our trainees learn to recognize when arguments are replaced by symbols, when reasoning is swapped for rhetoric. They practice the difficult art of sitting with uncertainty while still striving for clarity. Join us in this essential work We’re building a community of readers and supporters who recognize that, in an age of fragmented reasoning, we need those who can carry thoughts to their completion more than ever. Your engagement helps us expand this crucial work — whether by participating in our public workshops, supporting our internship program, or simply bringing a spirit of rigorous inquiry to your own reading and sharing of information. Roberta Campani Communications and Outreach P.S. For those who wish to explore these ideas further: Dive into Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality to explore the original formulation of cogito interruptus and much more. Join one of our upcoming workshops on media literacy and critical thinking, or reach out to discuss how you can support our training initiatives. Together, we can build a community that values completed thoughts in an age of convenient fragments. In a world awash in interpretive ink, we must preserve the bones of true understanding. | ||

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news

must

be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and

editors cost money.

So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

| ||

| ||

| About Publish with FO° FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact |

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment