| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Dear FO° Reader, Greetings from the Ozarks. Today, as the Islamic Republic of Iran is descending into a wave of protests and violence with the real possibility of armed US intervention, I want to talk about the “Islamic” part of the republic. We rarely hear about the “Islamic” part in Iran’s official name. We often take it for granted, assuming Iran is the same kind of Islamic as the rest of the region. In fact, it is vastly different and represents a distinct political project. The Islamic Republic of Iran was founded in 1979 based on the political-theological thesis developed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the first Supreme Leader of Iran. He articulated his thesis, commonly known as Velāyat-e Faqīh (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), most clearly in the 1960s. It relies on Twelver Shia, a religious sect that believes that the last of the twelve spiritual successors of the Prophet Muhammad will return alongside Jesus (Isa) and begin the Day of Judgement.

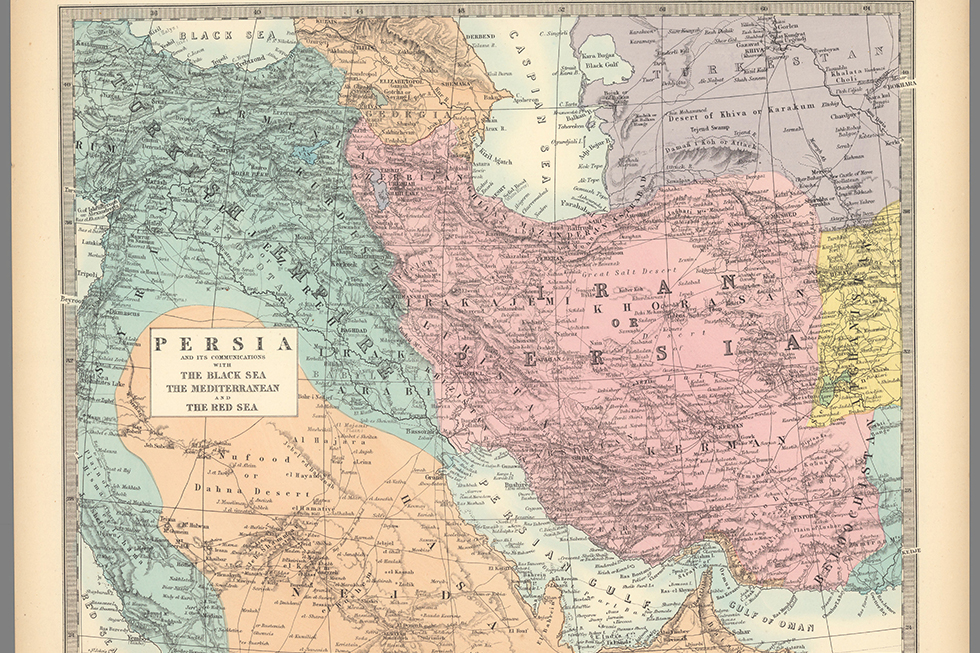

Iran or Persia with part of the Ottoman Empire, 1872 The belief is that the Twelfth Imam, the Imam Mahdi, is currently in occultation, or concealment, by God. During the absence of the Imam Mahdi, Velāyat-e Faqīh dictates that an Islamic jurist should assume political authority. In Khomeini’s framing, this system was meant to prepare society for the Mahdi’s eventual return. Sources: Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist | Wikipedia For centuries, mainstream Twelver Shia clerics largely stayed out of direct politics, believing that legitimate political authority could only be exercised by the infallible Imam. Many Shia scholars have argued that clerics should focus on jurisprudence, community guidance and moral authority rather than ruling. Political power, in this view, would fully return to Islam only upon the Imam’s reappearance. Sources: The Return of Political Mahdism | Hudson Institute Islam in Iran x. The Roots of Political Shiʿisms | Encyclopaedia Iranica Enter Khomeini, enter revolution Khomeini, however, having been exiled multiple times and witnessing what he perceived as the political marginalization of Shia communities and the dominance of secular or authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, proposed a radical departure from this tradition. He argued that Shia clerics must seize political power to protect Islam, implement Islamic law and actively prepare the ground for the Mahdi’s return. This marked a decisive break from classical Shia political quietism. Sources: The Iranian Revolution in the New Era | Hudson This logic is strikingly similar to Marxism and its later interpretations. Karl Marx argued that communism would emerge organically through historical processes and class struggle. Vladimir Lenin, however, rejected this passive expectation and insisted that the proletariat must seize political power first to bring about communism. In a comparable way, Khomeini — himself a Twelver Shia scholar — argued that Muslims must establish an Islamic state as a temporary but necessary mechanism until the Hidden Imam reappears. In this framework, the Islamic state functions as a holding authority, preparing society to assist the Imam when he emerges, including what Khomeini and later Iranian narratives describe as the liberation of Jerusalem. Sources: The State and Revolution | Marxists.org Ideology of the Iranian Revolution | Wikipedia What Is Velayat-e Faqih? | Tony Blair Institute for Global Change In sum, the “Islamic” character of the Iranian state is not a generic label but a deliberate political‑theological project rooted in Khomeini’s interpretation of Velāyat‑e Faqīh. By granting a senior cleric supreme authority, the regime fuses Shia eschatology with modern governance, using the promise of the Mahdi’s return to legitimize its domestic control and its regional ambitions. A shift in religion, a shove in politics The structure of this system is a theocracy, meaning that the leader of the country holds both religious and political authority. In Iran, the Supreme Leader is the head of state as well as the highest political-religious authority, typically an ayatollah with a recognized clerical following. While this role is sometimes loosely compared to the Pope, the comparison is limited: unlike the Pope, the Supreme Leader exercises direct control over the military, judiciary and key state institutions. Khomeini argued that Islamic law (Sharia) cannot be fully implemented unless Islam holds political power. Sources: Supreme Leader of Iran | Wikipedia Iran – Politics, Religion, Society | Britannica Now that we have outlined the thesis, it is important to understand why Khomeini developed it. He explicitly framed Velāyat-e Faqīh as a preparatory project for the return of the Mahdi. Thus, religion and politics have become closely intertwined in Iran. The structure of this system is a theocracy, meaning that the leader of the country holds both religious and political authority. In Iran, the Supreme Leader is the head of state as well as the highest political-religious authority, typically an ayatollah with a recognized clerical following. While this role is sometimes loosely compared to the Pope, the comparison is limited: unlike the Pope, the Supreme Leader exercises direct control over the military, judiciary and key state institutions. Khomeini argued that Islamic law (Sharia) cannot be fully implemented unless Islam holds political power. This is why nuclear weapons becoming a defining feature of the Islamic Republic tells us a great deal about its ideology. The incumbent Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei issued a fatwa, or legal ruling on Islamic law, stating that nuclear weapons are haram — taboo — and should not be pursued. However, urgency to act decisively — especially if Iran’s leaders believe it is necessary to develop a nuclear policy — could influence such decisions and might allow nuclear weapons. Sources: Jesus Will Return with Imam Mahdi | Ancient Prophets for a Modern World Mahdi | Definition, Islam, & Eschatology | Britannica The nuclear fatwa that wasn’t—how Iran sold the world a false narrative | Atlantic Council The Iranian regime has spent decades and significant resources educating its cadres, officials and institutions in a worldview rooted in Velāyat-e Faqīh. Anthropologist Narges Bajoghli, who spent over a decade studying generational dynamics within the Islamic Republic, argues that younger generations of regime insiders are often more ideologically rigid and revolutionary than the older generation, which fought the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s and tends to be more pragmatic. This dynamic illustrates how the regime continuously reproduces and radicalizes its ideology through education, media and institutional socialization. Iran’s revolutionary export becoming an import? An important question arises here: if the Iranian regime collapses, how would this group, trained on the same ideology and very well organized, disappear and let other forces take over the state? The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which forms the core of the Islamic Regime, might try to retrieve and start a guerrilla warfare similar to the Taliban. The Taliban was initially a student organization that trained its members on a particular Islamic ideology. Additionally, the regime has effectively created a group that supports it, and it is very well organized. It has, at the same time, disbanded any group or party, leaving the dissidents without any real organization or leadership. Sources: Iran’s Other Generation Gap, 40 Years On | Foreign Affairs Iran has also used this ideology to export its revolution in a manner comparable to how the Soviet Union once used communism to expand its influence. Iranian-backed groups have spread across the region. In Iraq, for example, several armed and political factions are deeply entrenched within the state, and many of them profess loyalty to the Supreme Leader of Iran rather than to Iraqi national institutions. Sources: Iran’s Proxies: Entrenching the Middle East | IDF This ideological framework is also evident in Iran’s regional and global narratives. Regionally, Iran presents itself as a protector of minorities and claims to have built a network to unite them against oppression. In practice, this network includes not only Shia groups but also Sunni factions, Christians and Yazidis, particularly in Iraq. This alliance structure is commonly referred to as the “Axis of Resistance.” The narrative places particular emphasis on sovereignty, which in practice often means resisting or excluding American and Western influence from the region. Nevertheless, Iran itself is a multiethnic state, and minorities such as Kurds and Baloch frequently report political, cultural and economic marginalization. Sources: Axis of Resistance | Wikipedia World Report 2024: Iran | Human Rights Watch Globally, Iran’s narrative, much like that of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, claims moral superiority and promotes its model of governance as an alternative to Western liberal democracy, which it portrays as corrupt, imperialistic and incompatible with true justice. Although nowadays the broader Iranian population has turned away from Islam or become less religious. However, even with over a million converting to Christianity, the Twelver Shias still dominate the state and continue to pursue their ideological goals. Source: Iranians’ Attitudes Toward Religion: A 2020 Survey Report | GAMAAN Further confrontation would likely reinforce their beliefs, as their narrative frames them as holders of the truth threatened by others. The future remains uncertain as violence and protest rage through Tehran’s streets as decades of resentment boil over. Given its deep roots, this part of Iran would probably survive even without the Islamic Republic. While the doctrine continues to shape Iran’s foreign policy and its narrative of resistance, mounting social unrest, generational shifts and increasing secularization suggest that the ideological foundations are being tested from within. Whether the system endures will depend on how resilient this fusion of religion and state proves in the face of internal dissent and external pressures. Wishing you a thoughtful week, Farhang Faraydoon Namdar and Casey Herrmann Assistant Editors Further readings

Podcast

| ||||||||||||||

We are an independent nonprofit organization. We do not have a paywall or ads. We believe news

must

be free for everyone from Detroit to Dakar. Yet servers, images, newsletters, web developers and

editors cost money.

So, please become a recurring donor to keep Fair Observer free, fair and independent.

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| About Publish with FO° FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact |

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment