As with any question that concerns the relationship between the US and China, commentators and pundits on this month’s San Francisco summit could reach no consensus concerning its historical significance or whether we should consider it a success or a shameful failure.

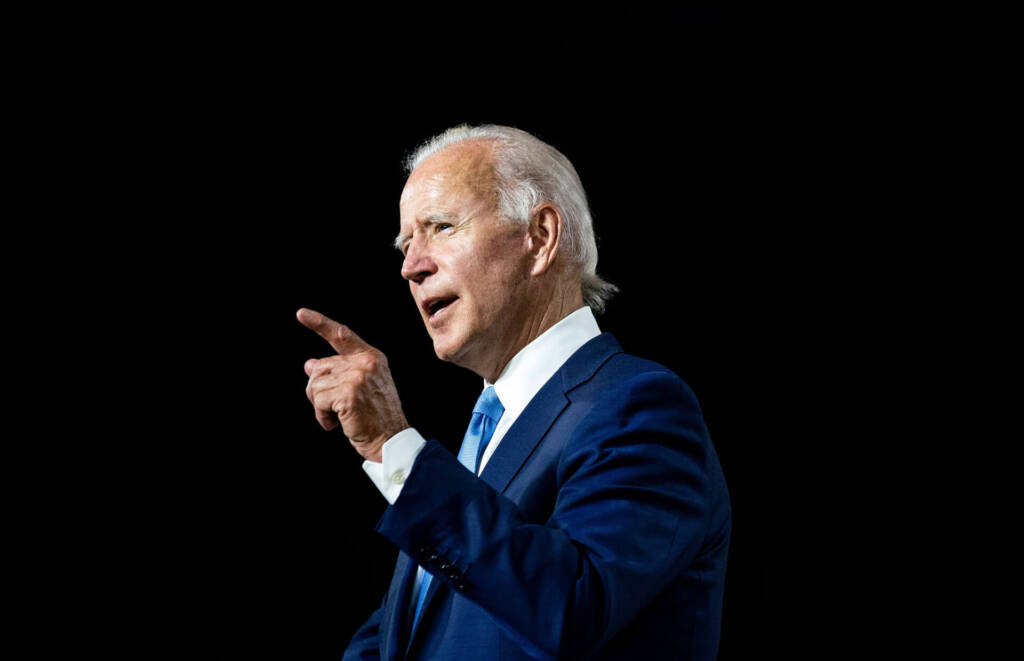

Both nations declared the outcome of the summit globally positive, but US President Joe Biden took the opportunity to indulge in a moment of provocation when he referred to Chinese President Xi Jinping as a “dictator,” repeating a remark he had made earlier in the year. In response to a reporter’s question about his view of Xi, Biden explained: “He’s a dictator in the sense that he’s a guy who runs a country that is a communist country that’s based on a form of government totally different than ours.” The Chinese reacted by calling that statement “irresponsible political manipulation.”

Is this simply a case of US culture valuing directness and the supremely American virtue of “speaking out” in contrast with Chinese culture’s commitment to harmony? At one point during the summit, Biden had this to say about the manner in which the two leaders conducted their exchange: “Just talking, just being blunt with one another so there’s no misunderstanding.”

Today’s Weekly Devil’s Dictionary definition:

Blunt:

- The opposite of sharp

- In the metaphorical diplomatic language of US President Joe Biden, “not sharp” in the sense of blurted without thinking of the consequences.

Contextual note

Was there “no misunderstanding?” Biden has had nearly three years to work out his relationship with Xi and with China. He has spent most of that time skirting the issue. As a politician, he can’t afford to appear soft on the rising Middle Kingdom. China-bashing has become a popular pastime amongst US voters and Republican politicians. Those in the business community who, to the contrary, seek a harmonious relationship with the Middle Kingdom have measured the interdependence of the two nations’ economies. For political professionals, seeking understanding with China is toxic.

During the 2020 election campaign, Democrats found themselves on the defensive as Donald Trump and Republicans made a spectacle of showing how tough they were on China. They accused Biden and Democrats of cowardly appeasement. That may explain why, in March 2021, at its first formal meeting with the Chinese in Anchorage, Alaska, not even two months after Biden’s inauguration, the US delegation insisted on appearing intransigent and confrontational.

Most observers were surprised, especially as Biden’s central campaign theme turned around the idea that he would break with Trump’s brazenness and bombast. He sought to reassure the outside world. He promised to restore a culture of rationality, civilized dialogue and diplomatic seriousness in his foreign policy.

The first test was the high-level talks with China in Alaska. Instead of appealing to the idea of mending the fences Trump had broken, Secretary of State Antony Blinken took on the role and tone of a prosecutor in a courtroom as he intoned a litany of complaints about Xi’s policies. He voiced Washington’s “concern” that China’s “actions threaten the rules-based order that maintains global stability.” White House adviser Jake Sullivan piled on. BBC reported that “Mr. Sullivan hit back, saying Washington did not seek a conflict with China, but added: ‘We will always stand up for our principles for our people, and for our friends.’” Clearly, he didn’t include China among the “friends.”

A historian attempting to describe the Biden administration’s approach to building a relationship with Beijing — as demonstrated in the 2021 meeting in Anchorage, Alaska — might be tempted to call it metaphorically “an attack with a blunt instrument.” The Chinese may have found this more mature, but hardly more rational, than Trump’s occasional, but largely innocuous, ravings. The obvious friction of that meeting in Alaska certainly produced its effects inside the US, exacerbating the idea that had been circulating in the background for some time that war with China in the coming years was inevitable, if not imminent.

Diplomacy used to have its traditions. One of them was that the first meeting between members of a new White House administration and another major power would, at least superficially, emphasize cordiality, respect and civility. Such encounters typically aim at creating a minimal level of trust and an environment that opens the door to constructive dialogue. Such diplomacy has always respected one of the deepest customs in Asian cultures, where time must be taken to establish a relationship before getting down to any kind of serious business.

Apart from obligatory handshakes, the spectacle surprised even US media. CNBC succinctly summed up the discussions in Alaska led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken as “an unusual public display of tensions.” This left everyone wondering what November’s meeting in San Francisco might produce. More of the same? A breakthrough? Or even the kind of “reset” Hillary Clinton promised Russia back in 2009 when she began running Barack Obama’s State Department?

Historical note

It’s much too early to begin to assess the historical significance of those two meetings in Alaska in 2021 and San Francisco in 2023. In the hiatus between the two events, the shape of international relations has radically evolved, largely as a result of the Ukraine war. The shift from the unipolar world that had become the norm after the fall of the Soviet Union to a multipolar world has been dramatically confirmed.

In 2021 Sullivan could boast: “Secretary Blinken and I are proud of the story about America we’re able to tell here, about a country that under President Biden’s leadership has made major strides to control the pandemic, to rescue our economy and to affirm the strength and staying power of our democracy.”

After less than two months in office, was the pandemic under control? Had Biden rescued the economy? Was the belief in US democracy strengthened? If you ask those questions to Americans today, the answers to all those questions are more ambiguous than ever.

As for the relations with China, Biden can credibly insist that Xi holds dictatorial powers over China’s central government — but does that make him an evil dictator? China has a remarkably decentralized political system in which, despite a clearly centralized control at the national level by the CCP, local governments wield far more power over people’s lives and environments than local governments in the US. Though Biden describes global tensions as a competition between democracy and authoritarianism, the evidence shows that US democracy, whose lawmaking is largely conducted through the mediation of lobbies, has become indistinguishable from corporate oligarchy.

In other words, the reality of global hegemony is not only about military power, financial clout and political influence. It is also about perception. For decades, the US has excelled in exercising its soft power, projecting an image most people across the globe found attractive. The Biden administration has done little more than confirm the impression Trump’s administration had offered to the world: that the soft power of the US, transmitted through Hollywood, TV and celebrity culture, may be little more than an illusion designed to cover up sheer hegemonic will.

The Chinese position in Anchorage, as exposed by Yang Jiechi, sounded empathetic and liberal. “And the United States has its style, United States-style democracy. And China has the Chinese-style democracy. It is not just up to the American people, but also the people of the world, to evaluate how the United States has done in advancing its own democracy.”

In contrast, Blinken offered this thought: “I recall well when President Biden was vice president and we were visiting China … Vice President Biden at the time said it’s never a good bet to bet against America, and that remains true today.”

For the rest of the world, that kind of language is hard to distinguish from mafia rhetoric. It highlights Noam Chomsky’s characterization of US foreign policy, in his book Withdrawal, as resembling that of a “godfather.”

Yang at one point insisted that “the United States itself does not represent international public opinion, and neither does the Western world.” Thanks to the war in Ukraine and now Israel’s war on Gaza, that has become an obvious truth, even if the Western media insist on ignoring it.

*[In the age of Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain, another American wit, the journalist Ambrose Bierce produced a series of satirical definitions of commonly used terms, throwing light on their hidden meanings in real discourse. Bierce eventually collected and published them as a book, The Devil’s Dictionary, in 1911. We have shamelessly appropriated his title in the interest of continuing his wholesome pedagogical effort to enlighten generations of readers of the news. Read more of Fair Observer Devil’s Dictionary.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment