Satipatthana Sutta contains the most succinct description of mindfulness. This meditation style and the accompanying philosophy are currently enjoying widespread popularity in the Western world. In India, Guru Goenkaji’s Vipassana retreats based on teachings from Satipatthana Sutta have been flourishing for the last 30 years. Vipassana is translated as “insight” and satipatthana is translated as “establishing mindfulness”. The way to gain insight into the nature of life is by developing and practicing mindfulness as prescribed in Satipatthana Sutta.

What is so appealing about the wisdom contained in Satipatthana Sutta for the contemporary lifestyle? The following is the initial paragraph of Satipatthana Sutta prescribing the practice of the four foundations of mindfulness as a direct path for the purification of beings on the way to realization of nibbana, translated as “ultimate liberation”.

“What are the four? Here, monks, in regard to the body a monk abides contemplating the body, diligent, clearly knowing, and mindful, free from desires and discontent in regard to the world. In regard to the feelings a monk abides by contemplating the feelings, diligent, clearly knowing, and mindful, free from desires and discontent in regard to the world. In regard to the mind a monk abides contemplating the mind, diligent, clearly knowing, and mindful, free from desires and discontent in regard to the world. In regard to the dhammas a monk abides contemplating the dhammas, diligent, clearly knowing, and mindful, free from desires and discontent in regard to the world.”

To many, the description in this paragraph may appear obscure, dry, boring, or simplistic. However, it would not be an exaggeration to say that this paragraph contains the psychology of wellbeing! This deceptively simple paragraph hides layers and layers of “how to” advice on facing and overcoming the universal difficulties life poses for us.

The Sutta goes on to clarify details of this practice in just about six standard size pages. In today’s language, mindfulness in Satipatthana Sutta can be paraphrased as : to diligently cultivate awareness of the present moment, simply observing, paying attention to facts and only facts and not getting caught in the judgments, with the intention of freeing ourselves from intense craving and intense aversion. This awareness is to be cultivated for the body, feelings, thoughts and mental patterns, and dhammas — which are the teachings on wholesome lifestyle leading to balanced and joyful existence. The details of dhamma include the basic tenets of Buddhism: four noble truths and the eightfold path. It includes discussion on the “joyful” existence as well. But the way to get there is through mindfulness — a special type of awareness.

What is it about this that has been corroborated by Western science? Although the above description of mindfulness makes sense for balance and evenness of mind, how does it exactly give rise to “joy” or even “bliss”? What are the other details in Satipatthana Sutta and other related teachings that address the psychological processes or the functioning of the human mind? In order to address these questions, it is helpful to understand the historical events leading to how mindfulness penetrated the Western psyche, and gained a huge following.

History of Mindfulness in the US

Although mindfulness is a foundational practice in all different schools of Buddhism, the form of mindfulness meditations as described in Satipatthana Sutta is attributed to Theravada Buddhism. Mindfulness and insight meditation (vipassana) have become the central focus of the way Buddhism is practiced by American Western practitioners, as opposed to the ritual and chanting based practices in Asian Buddhist temples. The origins of Western Buddhism can be traced to the first Theravada retreat center called Insight Meditation Society founded in 1975 in Barre, Massachusetts. The three founders, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, and Sharon Salzberg, were American Buddhists who had returned back to the US after spending a few intense years in Asian and Indian monasteries. This in itself may have remained at the level of a myriad other Asian/Indian practices that have become part of the American landscape. However, three main movements happening in the late eighties and early nineties contributed to the explosive popularity of mindfulness as a psychological tool for increasing mental and physical wellbeing.

First was the great interest in Buddhist ideas by Western scientific community for applying modern research methodology and testing in labs. Second was the secularization of mindfulness as a tool for wellbeing. And the third was the explosion of methodological advances and new discoveries in brain research.

The first can be attributed to his Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama opening up the field of Buddhist claims for psychological transformation to the world of scientific studies. He began holding conferences with Western scientists, co-founded the Mind and Life Institute in 1987, and showed a willingness to reject Buddhist claims if science proved them wrong. The second event that pushed mindfulness into the mainstream was that in 1979, the MIT trained molecular biologist and meditation expert John Kabat-Zinn, realized that the practice of mindfulness did not need to have religion attached to it.

Buddhism lends itself beautifully to secularization because the discourses do not have any mention of a God. For example, Satipatthana Sutta does not have any ritual, religious imagery, or any discussion of a God image. Kabat-Zinn came up with the 8 week long program Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and offered it to the group of patients with chronic pain issues at the University of Massachusetts Hospital. He conducted scientific studies to see if the program indeed reduced stress.

After a few successful studies, MBSR was being used in several hospital settings with patients dealing with high stress. Stress was and continues to be a huge concern in today’s world, so a non-invasive program such as MBSR became a very attractive option for the medical as well as the professional community. The program’s popularity allowed researchers to test MBSR and related programs in behavioral studies with control groups to check its efficacy in reducing mental health issues as well as enhancing cognitive capabilities.

Mindfulness as a Psychological Tool for Increased Wellbeing

Siddhartha Gautama searched for years for the anecdote to the universal experience of pain and suffering which resulted in his teachings. As His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama says, “Since the primary motive underlying the Buddhist investigation of reality is the fundamental quest for overcoming suffering and perfecting the human condition, the primary orientation of the Buddhist investigative tradition has been toward understanding the human mind and its various functions. The assumption here is that by gaining deeper insight into the human psyche, we might find ways of transforming our thoughts, emotions and their underlying propensities so that a more wholesome and fulfilling way of being can be found.”

When Buddha talks about “liberation” or “realization of nibbana” as the ultimate goal of his way of leading life, it can be interpreted as the liberation from experiencing misery and moving more towards increased wellbeing. The main modality to internalize the Buddhist teachings on wellbeing is through mindfulness.

There are a few different tracks in which the psychological processes in mindfulness and the dhammas can be understood. 1) By looking more closely at the teachings of the Buddha and his followers from India and other Asian countries where Buddhism spread. 2) By looking at what the scientific research suggests, which explains the promise of mindfulness as a way to deal with mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. 3) The third way of understanding the use of mindfulness as a psychological tool is to look at its implications for dealing with difficult emotions such as anger, shame, jealousy, addictions, and difficult to change mental patterns. The not-so-obvious aspect of this sutta is that it is an amalgamation of foundational thinking from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Positive Psychology, and Humanistic Psychology.

Track 1: Closer Look at Buddhist Teachings on Mindfulness

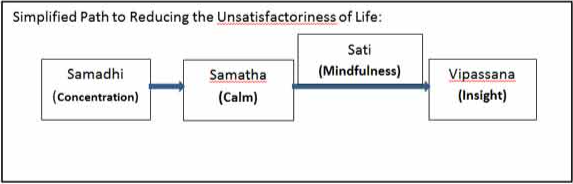

The following are the overlapping stages in the journey towards liberation from the Theravada Buddhist teachings, not necessarily sequential, but typically progressing in the way shown. This is derived from Analayao’s excellent scholarly analysis of Satipatthana Sutta which takes only the aspects relevant for our contemporary understanding of mindfulness, with the intention of not getting caught in the maze of interpretations.

Stage 1: Concentration (Samadhi)

Developing the ability to concentrate in the right way is advised as the prerequisite to achieving the later stages. Before practicing the meditations based on Satipatthana Suttas, oftentimes, the meditator is asked to practice anapanasati sutta which is to meditate to be mindful of the body sensations while breathing in and breathing out. Anapanasati is translated as “mindfulness of the inhalation and exhalation”. The word samadhi means concentration or meditation with absorption. In order to achieve the ability to be in the samadhi state, the meditator trains the mind to return to the experience of the breath once it is noticed that the mind has left the present moment.

There are four types of absorptions (jhanas) prescribed for achieving the right (samma) type of concentration. Without getting into the details of jhanas, one can still understand that Samadhi is supposed to lead to calmness. Budhha’s teachings often mention this type of breath awareness meditation as a core meditation for training our mind to concentrate with full absorption and with complete objectivity – observing the breath without deliberately changing it in any way. Our mind wanders around to the past or to the future, oftentimes to regrets or worries. Although this wandering around may have been built in as an evolutionary survival tactic, this decreases our awareness of the privilege of the present moment. In the process of this training, the meditator is also working on removing the five hindrances (explained in Stage 5) and purifying the ability to contemplate calmly and objectively.

Starting with anapanasati, other mindfulness meditations choose the object of focus as body sensation or a mental image, the effect of which is to train in concentration. In the contemporary language, such meditations are referred to as focused attention (FA) meditations. The modern mindfulness movement has taken this concentration training from FA meditations as a boon in itself for obvious reasons. Not only because the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Disorder in children has multiplied by several factors, but because new digital devices have created an inability to stay on task.

In the business world, the ability to focus is highly valued. Ironically, research shows that the ability to multitask improves with an eight week long, once a week mindfulness training which includes breath and body awareness. The ability to concentrate better is associated not only with focus, but with better emotional regulation and less depressive thoughts. What makes this type of meditation significant and attractive is the “calmness” that this samadhi is supposed to achieve and the intended effect of removing the five hindrances (see stage 5 for the explanation of hindrances).

The criticism of the contemporary use of FA meditations is that Buddhism emphasizes the “right” type (samma) of concentration. This refers to developing concentration with the intention of ultimately allowing internalization of dhammas without temptation to fall into an unwholesome lifestyle. For example, if not done with the right intention, a thief could use the concentration training to do an excellent job of robbing a bank.

Stage 2: Calm (Samatha)

Deep concentration creates inner stability and integration which is the calmness or samatha stage. Deep absorptions (jhanas – a deeper way to concentrate) create states of happiness and bliss and yet, at the same time, the intention is to remove clinging to this joy. With that training, the samatha or calmness is supposed to be for removing passion – or intense craving. Samatha is prescribed as a platform necessary for further realization or liberation. Only through a calm mind can one think rationally and see things “the way they are.”

As the venerable Bhante Gunaratana says, “The practice of serenity meditation aims at developing a calm, concentrated, unified mind as a means of experiencing inner peace and as a basis for wisdom.” Just like mindfulness of breath and body is used for reaching deep absorption leading to samatha, other objects are chosen in different Buddhist sects for developing the calmness. There are forty such objects chosen for concentration and calmness, ten of which are called kasina. These ten objects are objects such as earth, water, fire, air, and different colors. In the contemporary use of Buddhist style of meditation, environmentalist and peace activists have popularized meditating over these objects with the intention of respect and harmony with nature.

Stage 3: Mindfulness (Sati)

This is where Satipatthana Sutta plays the most crucial role in prescribing how and why to become mindful. Between concentration (samadhi) training and developing insights (vipassana) is the skill the practitioner must have, mindfulness. Look at the paragraph from Satipatthana copied in the beginning of this article. Sati or mindfulness is to be cultivated diligently. The aim is to be “clearly knowing” about the way things are and “free from desires and discontent in regard to the world”. This refers to the non-attachment, which in this context means removal of intense craving and intense aversion.

For all practical purposes, the craving and aversion together create misery in our lives and keep us imprisoned into our own clinging. The way to cultivate non-attachment through mindfulness is to objectively notice and internalize the Buddhist notion of emptiness of objects. Sometimes emptiness is misinterpreted as “nothingness” or nihilism. However, emptiness is the realization that no object stands as a permanent or independent entity with a fixed identity. Emptiness can be beautifully explained as a combination of two most important laws from Buddha’s teachings: the Law of Impermanence and the Law of Interdependence.

The Law of Impermanence states that everything changes, including experience of breath, body sensations, feelings, thoughts, mental images, mental habits and values. As the meditator is diligently paying attention to these factors, they realize that everything will pass. The Law of Interdependence becomes obvious when observing feelings and thoughts as not stand alone entities. In fact, one action gives rise to something else and this ripple effect will be experienced by the meditator depending on which sense sphere they are standing in at that time. Realizing emptiness implies not to take our current experience so seriously and not to react impulsively and is the foundation of developing non-attachment.

In Goenkaji’s Vipassana retreats based on the Burmese Theravada tradition, he teaches to sit through the uncomfortable body sensations without doing anything about it – without scratching when the skin itches. Similarly, when the meditator is feeling something, they learn to observe it with curiosity instead of immediately acting out. Just like the psychiatrist Victor Frankel said, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

This space is where freedom lies. In Goenkaji’s retreats when one is sitting through the bodily discomfort without moving, the habits (samskaras) of reaction from several births are being redirected or removed. Breaking of mental and physical habits – samskaras – is one of the goals of practicing satipatthana.

The goal of contemporary use of mindfulness is a “limited” version of true liberation (nibbana) from all types of suffering as described in the Satipatthana. The goal is to reduce stress by understanding the Law of Impermanence and by changing the mental habits of viewing yourself and the world around you in a fixed way. The goal is not to develop non-attachment to all cravings and aversions, but to become less judgmental, tolerant, flexible, objective, and to observe disturbing events without getting immersed in the feelings. In fact, the word “non-attachment” may not even be mentioned in mindfulness classes. Some practice mindfulness in a residential retreat setting, while some may choose to do it at a light or moderate pace in a class. Regardless, a change in attitude seems to take place corroborated by the brain structure changes noticed in neurological studies. Research studies at Harvard Medical School have shown that just about eight weeks of practicing mindfulness meditations for 27 minutes a day changes the brain structure in a way that anxiety is reduced and cognition, memory, perspective taking, and emotional regulation is improved.

There are a few concerns about casual practicing of mindfulness without realizing the full implications of internalizing non-attachment. Some may become stoic or disenchanted with lives’ pleasures. Some may escape into meditations when things get difficult to avoid critical thinking. These implications are possible if one does not consider the importance of dhammas in practicing mindfulness. Dhammas not only add joyful emotions to one’s experiences but they also emphasize the value of wisdom to know when to accept things and when to undergo discomfort for the sake of resolving things.

Stage 4: Insight (Vipassana)

The typical progression through this path towards liberation can be described as follows. The practice of samadhi will lead to samatha. This will create a good foundation for practicing mindfulness as in Satipatthana Sutta. This will lead to vipassana or insight into the nature of suffering and the liberation from suffering. Samatha and vipassana are supposed to be two balancing factors towards wisdom of non-attachment because they remove intense desire and ignorance respectively.

When a meditator is practicing satipatthana, they can employ two styles of meditations. First is FA meditation by concentrating on a specific object such as body, feelings, mind, or dhammas. The second is open monitoring (OM) meditation which does not focus on one object. The awareness is open and whichever one of the intended objects (body, feeling, mind, dhammas) catches the meditator’s attention gets full observation for some time. Then the meditator again notices where the attention is going and attends that object for some time. One can say that in the OM meditation, the meditator is becoming aware of the awareness itself. While FA meditation will train the meditator mainly in concentration and comprehension, OM meditation allows a restful state leading to a flexible mindset which can result in creative problem solving. This type of meditation may directly result in psychological insights into one’s own psyche.

The contemporary use of insight meditation is less to do with true insight into emptiness (as intended in Buddhist teachings), and more to do with psychological insights into oneself. For example, if a practitioner is experiencing an intense emotion or is trying to choose between careers, they would focus and comprehend their predicament first, and then observe the feelings and thoughts that are coming to them in the OM meditation style.

While doing so, an insight about their own needs or the origin of their own needs may fall into their lap. Some insight into what and why they should make a specific choice may suddenly flash in front of their mind’s eyes. This type of insight is corroborated by research on creative problem solving in which after complete comprehension and analysis of a problem, the problem-solver is advised to let go of the analysis and engage into a restful activity. This restful phase is likely to produce a creative solution to the problem. In research studies performed to test creative problem solving and mindfulness meditations, OM meditators were shown to have increased creative problem solving ability.

It is important to notice that sati and vipassana (mindfulness and insight) are supposed to produce wisdom. In the contemporary sense, wisdom can be defined as discernment or to know when to let go and when and how to fight.

Stage 5: Result of Practicing the Above Stages is to Remove Hindrances on the Path (Vineyya).

It is not a prerequisite to any of the above stages, but removed hindrances are supposed to be happening with all stages of practice. The practitioner is diligently removing the hindrances or obstacles to their practice simultaneously and in that process they are purifying and perfecting the platform for wisdom and liberation. The hindrances can be summarized as CRASH: craving, restlessness-and-worry, aversion, sloth-and-torpor, and hurry-for-results. All of which can create doubts about the practice.

Stage 6: Creating Ethical and Wholesome Lifestyle (Dhammas).

The contemplation of the dhammas includes contemplating the four noble truths and the eightfold path. The eightfold path includes three groups of factors, two right morality factors (right speech, right livelihood), three right concentration factors (right effort, right awareness, right concentration), and two right wisdom factors (right view, and right thought).

Contemplation and mindfulness of each factor can create joy by cultivating loving kindness and compassion towards yourself and others. The morality factors are crucial as you start walking on this path because they create expectations or intentions of ethical behavior that do not harm others. Some modern Buddhist scholars, such as Robert Thurman, think of Buddhism as a practice in ethics.

The genius of Buddhist teachings is to balance non-attachment with bramhaviahars. Satipatthana Suttas generate samatha and vipassana, however, their focus is to remove negative experiences by creating the armor of non-attachment around the meditator. In addition, Buddhist teachings focus on creating positive experiences for an individual and for a group by promoting practicing four bramhaviharas: four sublime states namely loving kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha).

Some aspects of this are discussed in the wisdom factors of the dhammas as well as other early Buddhist suttas including in Satipatthana Sutta. The later discourse written in the fifth century CE by Buddhaghosa in Visuddhamagga Sutta describes bramhavihara practice specifically, as documented by Ñanamoli in the translation “The Path of Purification”.

It is not at all surprising that bramhavihara practices, referred to as ‘metta practices’, have exploded in the Western countries in recent years as the positive psychology and happiness movement have gained such huge popularity. In fact, practitioners and researchers have been increasingly interested in researching positive and compassionate states of mind in order to create a more caring and unified world.[18] Bramhaviharas, in urging the practitioner to send loving kindness compassionate (metta and karuna) messages to even the people who are difficult in one’s life, create a happy intention. The sympathetic joy (mudita) proposes an antidote to jealousy and equanimity (upekkha) aims at evenness of mind based on compassion and integrity.

Mindfulness and ‘metta practices’ go together and mindfulness is a foundation for practicing metta in a balanced way. The practices of gratitude, altruism, self-compassion,self-acceptance, compassion-based therapy all originated from different types of ‘metta practices’. In Tibetan Buddhism, as practiced by His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, compassion-based view of the world’s problems is a norm.

The above are the ways in which Buddhist practices of mindfulness and metta are being used, especially in the contemporary West, as psychological tools for wellbeing. One can say that mindfulness offers a logical and fact-based approach to wellbeing and metta balances it by urging the practitioner to open up the heart and feel goodness.

In the next parts, we will address the two other tracks by which the psychological processes in mindfulness and the dhammas can be understood. Track two being the exploration of the most relevant scientific research and track three being description of the specific ways in which psychological predicaments, such as difficult emotions, are addressed in the mindfulness philosophy. One can say that the popularity of mindfulness and related practices has exploded because of its therapeutic value, on the individual level as well as on the level of the increasingly diverse, complex, and chaotic world we live in.

[Sutra Journal first published this piece.]

[Lane Gibson edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment