The coup that never was

When the army is restless and distrustful,

trouble is sure to come from other feudal princes.

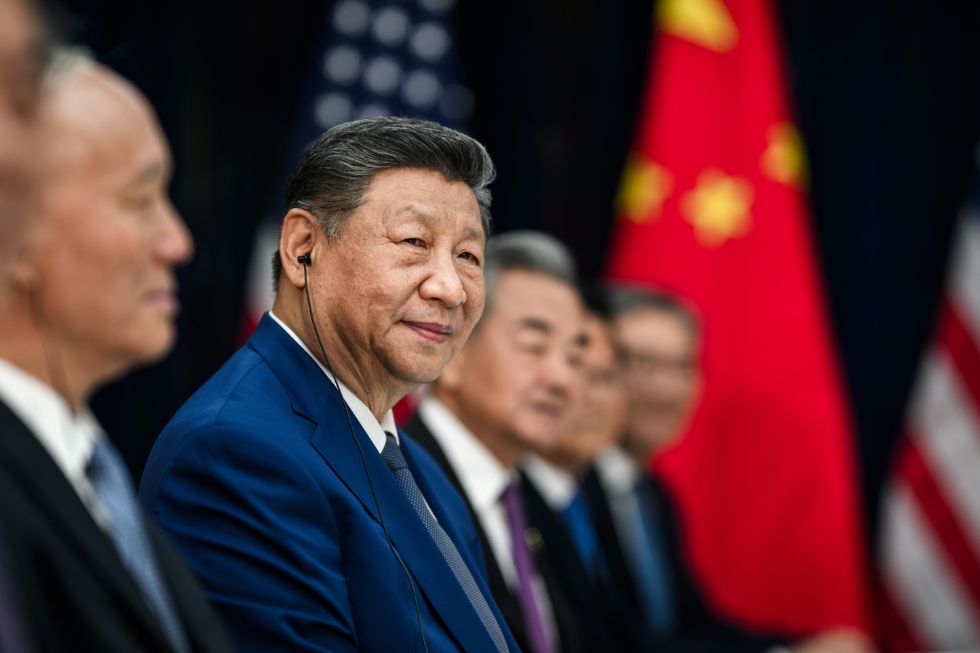

The arrest in late January of General Zhang Youxia, Vice Chairman of the Chinese Central Military Commission, spawned rumors of a coup d’état, with fringe Western media sources online showing AI-doctored videos of tanks purportedly in Beijing suburbs, and some even reporting gunfire around General Zhang’s residence. Wherever political systems are shrouded in secrecy and opacity, conspiracies flourish. China’s closed political culture, in particular, nourishes conspiracy theorists both domestically and abroad.

Debunking myths: understanding power dynamics within the Chinese Communist Party

The traditional Western commentariat has been somewhat constrained, yet it is still feeding the narrative that Chinese President Xi Jinping is under pressure from party factions, and that the arrest of General Zhang was an example of Xi’s struggle to retain presidential power through tenuous control of the military. Prominent US papers alleged Zhang was corrupt, selling officer commissions and even leaking nuclear secrets to the Pentagon.

No outsider can truly know what takes place within the labyrinths of power in the Chinese Communist Party (the Party), let alone the military, but the causes of General Zhang’s demise are more likely his strategic and tactical differences with President Xi, and his determination to pursue his own line, supported by a number of other senior commanders. This represented a faction or, at least, the seeds of one. That Xi moved against a figure as powerful as Zhang so swiftly and without tanks in the streets of Beijing demonstrated his power, not his vulnerability.

There is a China of common reality and a China of the foreign imagination. In the latter, the economy is always on the brink of collapse, and the government, led by recalcitrant communists, is mired in factional conflict. In reality, while social change over the decades has been radical, the day-to-day experience of both civil and public life is largely stable and predictable. The Party and government are stronger and more integrated with society than at any stage in modern Chinese history, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is obedient to the Party as never before, even more than under Mao Zedong.

Transforming the PLA: challenges, reforms and strategic aspirations

In 2013, a year after his ascension to power, Xi announced a series of military reforms. Former Chinese Leader Deng Xiaoping also drove military reforms in the 1980s, a time when units of the air force still practised formation flying with little models of Mig fighter jets in their gloved hands, moving in unison around basketball courts. China’s military had come a long way from the post-revolutionary, post-Korean War army, but was still backward, running exercises that were largely performative. Rivalry between the various branches of the armed forces was rife, and corruption was endemic. Commissions were traded widely, affecting advancement for even the lowest ranks and disrupting the meritocratic principles upon which the PLA was based. In 2013, the PLA still functioned much like a giant, inefficient state-owned enterprise, with more soldiers employed supplying food, uniforms and equipment than in fighting units.

China’s last significant military action was a limited incursion into Vietnam’s border provinces in 1979, in which both sides suffered heavy casualties, and after which both claimed victory. The US and Indian armed forces, on the other hand, have fought in a number of engagements, creating an experienced officer corps and competence in deploying modern weaponry. The ongoing reform of the PLA has been informed by China’s close observation of recent conflicts, particularly the Russia–Ukraine War, yet the modern PLA remains untested in combat.

Despite this, observers would be mistaken to assume that Chinese soldiers lack the logistical skills needed for combat, for the PLA is frequently deployed for disaster relief and has consistently met practical and leadership challenges, while winning the widespread respect of the people.

President Xi’s proposed changes to the PLA seem rational: the formation of small, flexible brigades that can respond to crises quickly and deploy mobile missile capabilities. He has expanded the Marine Corps to more than 50,000 soldiers to support China’s increased, largely defensive naval capacity and has invested heavily in drone and unmanned-submarine development. As the Ukraine–Russian conflict is demonstrating, drones are now a critical factor in battle, and China already has the capacity for the deployment of unmatched massed drone swarms.

It is significant that General Zhang was the last serving senior military commander with actual battlefield experience, which he gained in the 1979 war. His removal seems to undermine Western predictions that Xi plans to invade Taiwan next year. After a succession of purges, the Central Military Commission, chaired by Xi, has only two of the mandated seven members left. As much as he will need to establish a political succession plan should he take a fourth term, Xi now needs to appoint the next generation of military leaders to fill the vacancies his purges have created.

Rethinking Western strategies: a diplomatic approach to China’s military evolution

The West’s sense of exceptionalism and attendant lack of humility means that its policymakers and commentators alike often fail to appreciate the experimental nature of China’s political and industrial evolution and the scale of development across all parts of Chinese society. The Chinese military is no exception. The US and its allies will need to do better than invest in the poor science fiction that is AUKUS, or rely on the chimera that is the Quad to counterbalance China. They would benefit from reconsidering their conventional approach of holding annual war games in Chinese sovereign waters, which amount to sound and fury, signifying little and increasingly damaging diplomatic trust and trade relations.

There is little any power can do to stop China from continuing to develop a military commensurate with its demographic, geographic and economic scale. But the US and its allies’ actions can and will impact China’s perceptions of strategic and military threat. Unlike the US, China can point to its track record of avoiding military deployment outside its borders (with the exception of peace-keeping missions) for nearly 50 years, and it is unlikely to discard this record casually.

[Mahon China first published this piece as a business report.]

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment