Martin Plaut, a journalist, academic and author, delivers a sweeping historical account of African enslavement across five millennia, tracing its global routes, atrocities and lasting legacies. He further highlights its brutality and enduring impact.

Plaut opens with a quote from former African American slave Elizabeth Freeman: “Any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it — just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman — I would.” For Plaut, this testimony captures the essence of slavery’s horror and the immeasurable value of freedom.

The transatlantic trade

Plaut turns to the transatlantic slave trade, which lasted from 1444 to the 1850s. While the outlines are familiar, he emphasizes that tens of thousands also came from Portuguese and East Africa, some reaching the United States. Captors included Portuguese, British, French, Danish and others, each profiting from the vast human traffic.

He recalls the infamous Zong incident of 1781, which he calls “possibly the worst thing, the worst event of all.” The captain of the slave ship Zong claimed to be running out of water and threw 133 slaves overboard alive. The event became known only through a court case — an insurance dispute over “lost cargo.” To Plaut, the fact that human life was reduced to a financial claim demonstrates slavery’s cruelest logic.

Ancient and Islamic dimensions

Plaut observes that the enslavement of Africans predates the Atlantic system. Egyptian slavery along the Nile lasted centuries. After Muhammad’s death, Arab armies swept into Egypt, across North Africa and into Spain and Portugal. This conquest fueled Mediterranean and trans-Saharan trades, sometimes reaching as far as China. Large numbers, especially from Sudan and Ethiopia, were taken across the Red Sea to the Saudi Arabian city of Mecca, Iraq and Syria. These routes endured for generations, shaping populations far from Africa’s shores.

Plaut notes how enslaved Africans, usually men, were taken to India as military slaves. He cites military leader Malik Ambar, a slave from Ethiopia who defeated two Mughal emperors. Descendants remain in India and Pakistan, often called the Siddi ethnic group. Plaut comments that they “all have a pretty tough time of it,” reflecting on their marginalized status in modern society.

The Indian Ocean trade

He describes the Indian Ocean trade dominated by the Omanis. Beginning in the first century CE, it later expanded with Portuguese, Dutch and British involvement. Omanis relied on Indian merchants and financiers to organize activities and mercenaries from the Baloch ethnic group. The wealth was so immense that the Omani Sultanate moved its capital from Muscat in Oman to the Tanzanian archipelago of Zanzibar, a symbol of slavery’s financial engine.

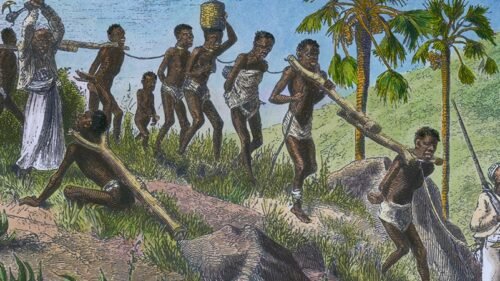

Plaut highlights Afro-Omani ivory and slave trader Tippu Tip, whose name echoed the sound of his guns. He cites the 1866 account of Edward Seward, the British consul in Zanzibar, who saw a caravan of 300 slaves. Purchased for mere cotton cloth, they marched nine hours daily and were fed only boiled sorghum and water. Men were bound in forked sticks; women and children were tied by the hands. Seward described children beaten to death and paths littered with corpses, a haunting record of human misery.

Enslavement in modern times

Plaut discusses slavery that continued into the twentieth century, showing a 1935 image of Ethiopian merchants and their slaves delivering money to Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie for his war against Italy. This, he observes, is an aspect of Selassie’s reign “not much commented on.”

The Sokoto Caliphate

Plaut explores the Sokoto Caliphate, an Islamic state that lasted a century and comprised 30 emirates from Cameroon to Burkina Faso. In the mid-nineteenth century, Sokoto may have held as many slaves as the four million in the US on the eve of its Civil War. Plaut finds it “extraordinary that something of such importance has somehow been missed.”

Measuring the catastrophe

Plaut estimates that across five millennia, “at least 50 million Africans” were enslaved. He also notes that present-day conflict zones often align with old slave routes. He suggests slavery’s destructive legacy persists.

Chains unbroken

Plaut ends with the image of former US President Barack and former First Lady Michelle Obama at the Door of No Return on Gorée Island, Senegal, in 2013. He calls it “extraordinarily uplifting” and proof that “injustice is not imprinted on history.” His talk, drawn from his book, Unbroken Chains: A 5,000-Year History of African Enslavement, reminds us that slavery’s story is ancient, tragic and still echoing.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment