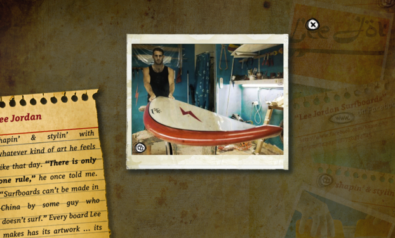

The following is the fifth of a six-part series of excerpts that Fair Observer will be featuring from Jesse Aizenstat's Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation. Author's Note Riding off the thrill of whipping out my second American passport and being allowed to enter Lebanon (with my other, Israeli stamped passport in my back pocket), I arrive in the country. But, the surf has fallen flat. After two weeks of waiting and meeting a cool Lebanese surfer called Monner, the surf finally picks up. Monner and I decide to make an early-morning run down to a place called Jiyeh, in the south of the country. We arrive and walk out through an abandoned beach resort to the Mediterranean. Surfing with Nasrallah At this dark hour, not a soul was around, and we both took a seat on the edge of the deck, our toes dangling off as a keen euphoria took hold of our under-slept minds. Our first glance at the Sea. The fine pre-dawn excellence in the air meant we had picked the right morning to come. By noon this place would be filled with all the plastically altered bodies known as “the young and wealthy of Lebanon.” But that was no problem. By that time, the wind would have switched directions and ruined the alignment of conditions that made this moment so serenely surfable. I turned my head in the darkness and could make out that there was a small village surrounding this resort. Slices of the wild Lebanese coast could still be seen—beautiful, perhaps even unaltered since the days of the ancient Phoenicians. “Wow!” Monner exclaimed. “It’s not big, but what would you say, chest, shoulder high?” Indeed, I thought, and nodded with gleeful approval. My stomach clenched with excitement. The wind was not blowing in from the sea as it often did in the afternoon. It was coming in from up the wadi, hitting my face as if I were in a wind tunnel. This lush mountain air had been storming across the Asian continent and out to the end of the line. Crisp waves broke over the Jiyeh sandbars. Their crests rose, rooster-tailing with huge spray, and left the water smooth and clean and perfectly rideable for my first morning of Lebanese surfing. The moment was here. “Oh yeah!” I said in a whipped craze of almost-mission-accomplished adrenaline. “We gotta get out there!” Barefoot, I jumped onto the grainy sand—as did Monner—and we started to wax the tops of our boards to give us grip. Monner was going to ride some kind of soft-top board, normally used for beginners, but it’s all he had here in Lebanon, as there were no surf shops. The closest one across the forbidden border wouldn’t be far, but venturing there was most definitely out of the question. Waxing in a circular motion, I uttered that it was too bad I hadn’t known him before or I would have gotten my buddy Lee to make him a board in Haifa. “Yeah, that would have been great!” Monner said, while spreading an oozing glob of sunscreen all over his face, making it zinc-white. And again, there was the beauty of Monner: he wasn’t big on Israel, but he wasn’t even close to being so rigid as to not accept a board from an Israeli. Looking out, I could see that the conditions were getting better. The sun was still hiding somewhere up the wind-blowing wadi, behind the mountain—as if the cool Asian air were actually making the difference in pushing that old fireball over the craggy peaks of ancient Phoenicia. “Next time I’m in America,” started Monner, “I’m going to get a fiberglass board like Che. Then I can really start surfing around here!” I looked at Che with a warm sort of friendship, perhaps knowing that he could never leave Lebanon . . . for this was his intended destination all along. He was built for these waves, and it didn’t seem right to part him from his journey, for he had also risked his foamy life to come here. It was too defining. Too important. He had passed through all the checkpoints and hassles that I had—minus the gassing at Bil’in—and our journey had really bound us together. But we weren’t there yet. With my toes in the sand and Che firmly tucked under my arm, I heard a fine-breaking set come crashing across the Jiyeh sandbars, peeling effortlessly without a soul out there to ride it. Monner and I knew the wonderful offshore wind—whiffing of the cedars of Lebanon—wasn’t going to last forever. So just as Lee and I had done 55 miles south in Haifa, we hurled our adrenaline-ridden bodies off the sand and into the Jiyeh sea, like two old buddies who had known each other forever. Finding a lull between sets, we enjoyed a smooth paddle to the outer calm of the break. It was then, as I sat upright on Che, that a strange feeling crept up my spine like a high that would never be felt again: Completion. Elation. Utter Sublime. The touch of God. A shooting star that proved Existence: I couldn’t have been closer to making my dream a reality. Being out in the Jiyeh break was an experience as radical as anything I had felt in the Middle East. Or anywhere, really. I was teetering on the finish. After all the hassles and planning for the better part of a year, I had figured out a way to surf on both sides of the Israeli-Lebanese border, and I had done it in a way that I could write about for the Surfer’s Journal, my first job out of college. But I had yet to catch a wave . . . and so it was just as the new day’s sun rose above the tallest peak of the deep valley that a set of maritime mounds started to rise from the depths of the sea. Monner and I were in position. He looked over at me with an expression that meant one thing only: Go man! This is yours! Softening my upright position, I extended my legs straight and slid my belly down on Che’s waxed deck. Cupping my hands, I reached forward to fully grasp the warm water and push it all the way through in long, powerful, strokes. I leaned left, positioning myself right under the steepest part of the rapidly building peak. I knew I would only get one shot at making this first crest of completion—and my first Lebanese ride had to be worthy. One paddle. Two paddle. Three! I could feel the power of the wave pick me up, making my long strokes in the sea irrelevant, for a new force had taken over. Arching my back, gripping the rails, I planted my front foot down, twisting it, and crouched all the way through—down the line, entering that sweet pocket that held me like a child, shepherding me through My First Ride, which could never be felt again. I shrieked with joy. Monner was smiling with approval. I was in the calm periphery of the break, drenched with ecstasy and slowing down as all the elements had come together for a wave that was downright mind-bending. Those first moments of completion were the absolute zenith of the trip. I couldn’t get any higher. I had fulfilled my desire to surf in the Middle East when I was in northern Israel. And now in Lebanon? Sweet Jesus! It was just great! With all the odds stacked against me—both figuring out a way to get to the Middle East and surfing around the Israeli- Lebanese border—I did what I had set out to do. I felt like an old man at peace with a well-lived life; or like an old blues guitar player, wailing a heavy lick through a screen of distortion, who finds that last needed note and massages it elegantly for a sweet payoff. That first Lebanese ride was the first time in my life I felt like I had completed something that made all the hassles and checkpoints and closed borders worth it. Like it had all come together. It was a feeling so rare and beautiful that who knows if I will ever feel it again? Frankly, who cares? Read the final excerpt from Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation on August 22. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment